On the evening of Aug. 2, 1930, New York Judge Joseph Crater and his wife, Stella, and their niece  drove from their cabin on Great Pond for a night on the town at Belgrade, Maine. Great Pond was one of the Belgrade Lakes, a chain of seven lakes in central Maine north of Augusta, where the Craters were long-time seasonal residents. That evening they went bowling and saw a film at the movie theater.

drove from their cabin on Great Pond for a night on the town at Belgrade, Maine. Great Pond was one of the Belgrade Lakes, a chain of seven lakes in central Maine north of Augusta, where the Craters were long-time seasonal residents. That evening they went bowling and saw a film at the movie theater.

At one point, Crater excused himself to make a phone call, most likely from the public telephone in town. When he returned to his wife and niece, he said something had come up, requiring him to make a quick trip to New York City.

Stella was surprised to hear this because he had just returned from the city that very morning, and he had planned to spend the next three weeks in Maine.

The next day, Crater took the overnight train to New York from Belgrade Lakes station. He promised to return to Maine by the following week in time for Stella’s birthday.

Stella never saw him again.

His sudden disappearance dominated the news for weeks and became part of the national folklore. “To do a Crater,” was slang for disappearing.

The Mercurial Rise of Judge Crater

Joseph Crater was only 41 years old when he went missing, after a meteoric rise in New York politics. Early in his law career he cast his lot with Tammany Hall, the corrupt Democratic political machine that controlled politics and the courts in New York City. The Tammany machine provided lawyers like Crater with lucrative public offices and influential clients. He caught the attention of political leaders in New York, including Gov. Franklin Roosevelt, who nominated him to fill a vacant position on the New York Supreme Court in 1930. The New York State Senate unanimously agreed. [Note: the New York Supreme Court is not the state’s highest judicial body, it is actually a trial court].

He and Stella met while he was still in law school at Columbia; they married in 1917. As her husband’s career blossomed, and his association with Tammany Hall deepened, the couple enjoyed the spoils of his success: a maid, a chauffeur, a Cadillac, an apartment on Fifth Avenue and the cottage in Maine.

But there was something else. Crater was a notorious womanizer. He enjoyed the nightlife of Manhattan, often visiting nightclubs and speakeasys in the company of show girls and actresses. He was known around Broadway as “Good Time Joe.” And he also had a longtime mistress, Connie Marcus, to whom he sent support checks since 1924. In fact, he sent her a check from Belgrade Lakes on Aug. 2, 1930, the day before he left Maine to return to New York.

Return to New York

Once in New York, Crater seemed to carry on as usual. He told his maid that he wouldn’t need her services at the Fifth Avenue apartment until Thursday, August 7, the day after he planned to return to Maine. He went to work in his office on Monday, lunched near his office building, and visited his doctor. That evening he went to a play, followed by a night on the town at a club frequented by gangsters. He lunched with colleagues on Tuesday, and later that night he played poker at a friend’s house.

By Wednesday, the August 6, Judge Crater’s behavior changed. His law clerks described him as taciturn, unlike his gregarious self. He spent part of the morning riffling through papers in his office and removing two briefcases of documents, which he transported to his apartment. He also asked one of his law clerks to cash two personal checks for him for substantial amounts. Oddly, he told one clerk he was heading to Westchester to swim.

That night, he ate at one of his favorite restaurants, where friends later told police that he seemed “nervous,” “disturbed” and “depressed.”

Judge Crater Last Seen

Crater was last seen getting into a cab in Manhattan after eating dinner on the night of August 6, 1930. As the days went by with no word, Stella back in Maine grew increasingly worried about her husband. Her birthday came and went, but still no Joe.

Incredibly, for the next month, nobody reported Judge Crater missing! Stella called several of her husband’s associates, and although nobody had seen Crater since August 6, they all assured her everything was fine and Joe would eventually show up. Most likely, they were worried that reporting him missing might affect his election campaign for a full term on the New York Supreme Court coming up in November. That is, assuming he turned up alive.

Neither the police nor the public learned of Crater’s disappearance until September 3, when newspapers got wind of the story, a month after he left Maine to return to New York. That’s one month of the trail turning cold.

On September 6, Stella, still in Maine, filed a missing person’s report with the New York Police Department (NYPD), and was visited the following day by a detective from the NYPD for informal questioning. Stella during this time was distraught and bedridden.

Focus on Maine

By now, Crater’s disappearance became a national craze. Sightings of the judge were reported in upstate New York, Vermont, Quebec, Maine, California and Arizona. Many of these sightings were followed up by detectives from the NYPD, and all proved fruitless.

Maine, of course, was a logical search site, given Crater’s long-standing association with the state as a summer visitor. Also, several witnesses who interacted with Crater in New York City between August 4 and August 6 later testified that he told them he would return to Maine after his business in New York was complete. And there was his promise to Stella that he would return to Maine in time for her birthday on August 9.

The Portland Press-Herald reported on September 5 that Crater was suspected to be hiding at a cottage on Long Pond, one of the Belgrade Lakes chain, but that proved unfounded.

Later, reporters staked out the Craters’ cottage, based on a rumor that he would make an appearance there, but reported no sighting of the jurist.

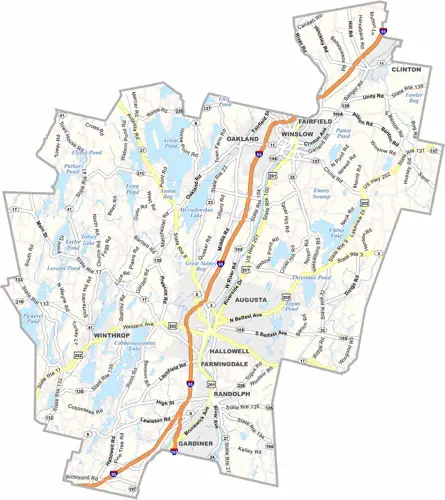

The Kennebec County Attorney launched a grand jury investigation, and dispatched Capt. Joseph F. Young, Jr., the deputy chief of the Maine State Police, to Belgrade Lakes on September 19 to search phone records and to interview neighbors. When Young appeared at the Crater cottage, two NYPD detectives had already arrived, conducting an unannounced interview with Mrs. Crater. This rankled the Mainers, who apparently resented this intrusion on their turf.

The Judge Crater Case Closed

By September 23, the county attorney closed the case, as it pertained to Maine, pointedly telling the district attorney in New York that the still distraught Mrs. Crater was in no state for interviews. He also said the New York detectives sent earlier to interview Mrs. Crater should provide any information the New York DA might need.

Stella was clearly an uncooperative witness. Her refusal to appear before the New York grand jury so irritated the DA there that he accused her of impeding the investigation. But there was little he could do but complain.

An Enduring Mystery

Stella remained in Maine for the rest of the year, leaving the cottage in October for a hotel in Portland. The case and public attention now centered in New York.

By Jan. 9, 1931, a grand jury in New York issued a final inconclusive report about Crater’s disappearance and dismissed the jurors. Crater would never be found, his disappearance a forever mystery.

Stella stayed at the cottage at Belgrade Lakes throughout the summer of 1931, and the following year got a job as a telephone operator. Strapped for cash, she was evicted from the Fifth Avenue apartment, but was able to hold on to the Maine cottage. She eventually remarried in 1938, a year before Judge Crater was officially declared dead. She and her new husband spent summers in Belgrade Lakes and winters in Waterville, before going their separate ways. Leaving Maine forever, Stella moved to Brooklyn in 1950, and died in upstate New York in 1969.

End Notes

James F. Lee, the author of this story, is a freelance writer and blogger whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Boston Globe, Philadelphia Inquirer, and AAA Tidewater Traveler Magazine. He can be reached at www.jamesflee.com.

Sources:

Finding Judge Crater, Stephen J. Riegel, Syracuse University Press, 2022, accessed via Hoopla, 2/18/2025; Vanishing Point: the Disappearance of Judge Crater and the New York He Left Behind, Richard J. Tofel, Ivan R. Dee Publishing, 1957, accessed via Internet Archive, 3/2/2025; Portland Press Herald, (Portland, Maine), Sept. 5, 20, 24, 1930, and Biddeford-Saco Journal, (Biddeford, Maine), Sept 11, 1930, accessed via Newspapers.com, Feb. 16, 2025.

Images:

Judge Joe Crater, half-length portrait, seated, facing front. , 1930. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001695145/.

40 Fifth Ave., Crater’s home. New York Fifth Avenue, 1930. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004670149/.

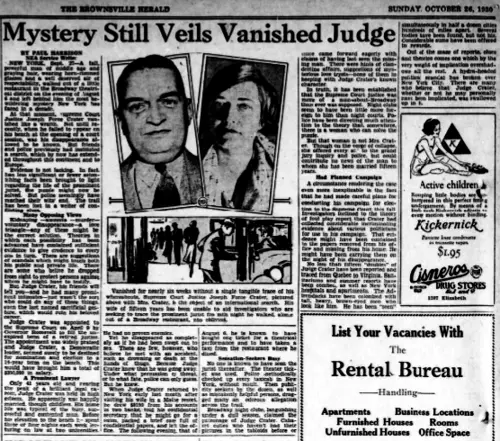

Crater photo, circa. 1925, Anonymous from https://news.lafayette.edu/2011/04/14/looking-back-new-novel-suggests-fate-of-judge-joe-crater-class-of-1910/ {{PD-US}}; “Mystery Still Veils,” Brownsville herald. [volume] (Brownsville, Tex.), 02 Nov. 1930. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063730/1930-11-02/ed-1/seq-12/>;

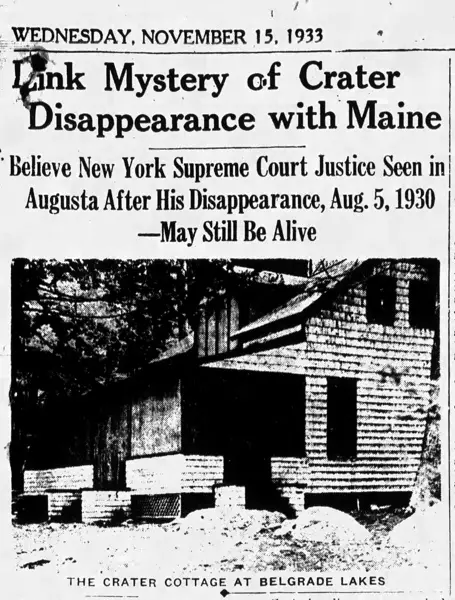

“Link Mystery,” Lewiston Evening Journal, Nov. 15, 1933, p.1. (Courtesy of Belgrade Historical Society, Belgrade, Maine); Belgrade Depot, (Courtesy of Belgrade Historical Society, Belgrade, Maine); Kennebec County map, (2025) Kennebec County Map, Maine – US County Maps.

New York County Courthouse By wallyg – Flickr.com, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1222205.