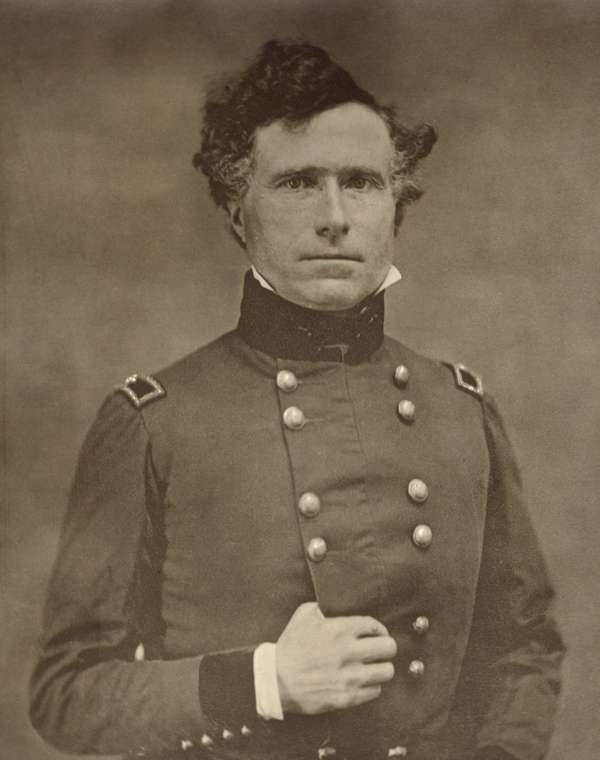

Twenty-four years after the last Adams vacated the White House, another New Englander moved in: Franklin Pierce of Hillsborough, N.H.

Unlike the Adamses, he was a handsome, gregarious, hail fellow-well-met. Pierce may not have been the brightest star in the presidential firmament, but at least everybody liked him when he took office. By the end of his presidency, practically no one did.

President Franklin Pierce

Few people know anything else about him anymore. That’s probably a good thing because historians rank him as one of the worst U.S. presidents.

But if presidents are allowed excuses for their poor performances, Pierce had one. He came to the White House overwhelmed by sorrow and guilt, and he faced an impossible task alone.

President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce in March of 1853 took the oath of office during a heavy snowfall. His wife, Jane, was away, his vice president, William King, lay dying in Cuba. Outgoing First Lady Abigail Fillmore caught a cold on the inaugural platform, which turned into pneumonia and killed her. A month later, King died.

William King

It was not a promising start…

When he won election as president of the United States, Franklin Pierce was an alcoholic from a small state who hadn’t held an elected office for 10 years.

He’d served as a two-term congressman and a U.S. senator from New Hampshire. The hard-drinking bonhomie of official Washington held out constant temptation to him. One day he had passed out drunk at his desk in the Senate chamber, snoring loudly. He woke up screaming, “Fire, fire!” A colleague asked where the fire was. Pierce rubbed his belly and said, “In here.”

First Lady Jane Pierce

No wonder Pierce’s wife hated Washington. She was her husband’s opposite, a religiously devout teetotaler who did not want him to lead a public life. Frequently ill and depressed, she kept to her rooms in the capital city while Franklin tended to his legislative business.

She tried to end his political career by forcing him to retire from the Senate. They had lost their eldest son, Franklin Jr., in infancy, and Jane didn’t want to raise their two surviving boys in Washington. Pierce, wanting to control his drinking, agreed to quit.

He returned to New Hampshire with his small family in 1842 to practice law. He even took a temperance pledge. For a while he stayed on the wagon, despite the loss of their four-year-old son to typhoid. He never ran for office, but he did stay active in Democratic Party politics.

Pierce for President

In 1852, the Democratic national convention in Baltimore deadlocked over a candidate for president. Pierce seemed like a good compromise. He was likable, and he didn’t have much of a political track record. But he did have a military record as a brigadier general in the Mexican War. He could probably win the election by appealing to Southern voters because of his views on slavery.

Gen. Franklin Pierce by Matthew Brady

“I am no advocate of slavery,” he wrote. “I wish it had no existence upon the face of the Earth, but as a public man, I am called upon to act in relation to an existing state of things.”

Pierce wasn’t even at the convention in Maryland when he won the nomination on the 49th ballot.

He and his wife were taking a carriage ride in New Hampshire when a horse and rider galloped up to them. It was a messenger come to tell him he’d won the nomination.

Jane fainted.

Tragedy Strikes

Just after the November election, Pierce and his little family visited Amos Lawrence in Boston. Then Lawrence died suddenly on Dec. 31, 1852. Franklin, Jane and their 11-year-old son, Bennie, went to the funeral. Afterward they stopped in Andover to visit friends. On January 6, they boarded the train back to Concord. The train hadn’t gone far when they felt a jolt and heard a sharp snap. The train tumbled over an embankment. Jane’s brother-in-law, Alpheus Packard, was in the car with them and saw what happened.

Jane Pierce and son Bennie

Pierce grabbed his wife and son, but Bennie slid through his hands and hurtled through the car. Flying wreckage struck the boy’s head, and when the railcar stopped his decapitated body lay on the floor. His head, covered with splinters, rolled in the aisle. Jane screamed. One of the passengers tried, but failed, to shield her from the sight. Another threw a shawl over the boy’s remains.

Pierce never got over it. Nor did Jane.

That Death’s Head

In late February, the Pierces took another train, to Washington for Franklin’s inauguration. But Jane got off in Baltimore and stayed there for weeks.

When Jane finally managed to come to Washington, she took to her darkened room. She had the public rooms draped with black bunting and spent most of her time writing letters to her dead son. Sometimes she invited local mediums to help her talk to him. Sometimes, behind the closed door, the servants heard her laughing and playing with her three dead children.

For most of her first two years as First Lady, Jane Pierce stayed in seclusion. When she did appear at White House social events, her obvious grief made the guests uncomfortable.

President Franklin Pierce Drinks Deep

Pierce held White House receptions every Friday from noon to 2 p.m. Huge crowds pushed their way into the mansion. Anyone could come, except Black people, who’d been barred from places of entertainment in Washington. The crowds trashed the already shabby White House and raised concerns about Pierce’s safety. In the volatile city, he decided to hire as bodyguard his old orderly from the Mexican War, Thomas O’Neil.

He went out a lot, to parties, the theater and concerts, but never alone. And he couldn’t stay away from the booze. “He drinks deep,” noted one journalist.

The decrepit state of the White House and grounds finally prompted Congress to appropriate $25,000 for its improvement. Pierce had the state rooms redecorated, the heating system upgraded and a bathtub installed with hot and cold running water. The grounds, too, got a reboot under the direction of head gardener John Watt. He would later be disgraced for conspiring with Mary Todd Lincoln to defraud the government.

White House state dining room during Pierce’s presidency.

Pierce showcased the White House’s new look in 1855 at the biggest event of the year, the New Year’s reception. Jane appeared at the party, dressed in black as usual and looking sad. It was not a demanding event for the kitchen staff, as no refreshments were served.

Beyond showing up, Jane had little involvement in planning White House entertainments. She did urge the servants to go to church for her sake.

Nothing Left

Rather than support his re-election, the Democrats chose to nominate James Buchanan. He turned out to be one of the few presidents historians think less of than Pierce.

When asked what he would do after leaving office, Pierce replied, “There’s nothing left…but to get drunk.”

* * *

Learn what life was like in the White House for New England’s six presidents. Click here to order your copy today.This story last updated in 2025.