In the year 1692, Massachusetts’ new royal governor William Phips decided he needed to get tough on witchcraft. The colony was losing the war against the French and Indians in Maine, just 10 years after the devastation of King Philip’s War. Refugees from Maine had streamed into Massachusetts, and many families had lost loved ones in the conflict. Not only were times hard, but the King had raised taxes to pay for the war.

Devout Puritans found this turn of events difficult to accept. For five decades, John Winthrop’s City on a Hill had grown and prospered. But now, it seemed, God was displeased. People stopped going to church, tippled in taverns and violated the dress code — evidence that Satan had undermined the great Puritan experiment.

William Phips, the governor who got tough on witchcraft.

On top of all that, Massachusetts’ leaders split into factions after King James II had recently tried and failed to combine the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies into one.

In such turbulent times, Phips had to do something to hang on to power. He resorted to the politician’s tried-and-true tactic of cracking down on crime. Only in his case, he got tough on witchcraft.

Getting Tough on Witchcraft

Phips was not your average Puritan leader. He came neither from England nor Massachusetts, but from the District of Maine, and Maine was a scary place in 1692. After the devastating losses of King Philip’s War (1675-1678), many surviving natives fled to Maine and, with their French allies, began another war. This was not a distant conflict. As the French and Indians leveled entire communities, refugees streamed into Salem and nearby towns. Men from Salem had lost their lives in Maine battles, and the war came frighteningly close.

People who came from Maine, therefore, had the whiff of the devil about them.

Phips grew up in present-day Woolwich, a frontier trading post, and never had an education. He was born on Feb. 2, 1651, one of 25 siblings, according to Cotton Mather (though that could be an exaggeration).

In addition to being a Mainer, there was something else scary about William Phips. He had won a knighthood by recovering a sunken Spanish galleon near Hispaniola. The shipwreck carried about $20 million in gold by today’s standards. Some suspected he’d found the gold through the magic arts. Others called him a pirate.

He had a couple of other strikes against him. He and his wife had no children of their own, and witches were believed barren. In his household, he had two suspect servants: one an enslaved black man, the other a French Catholic servant.

The Mathers

Phips, like many weak political leaders, was heavily influenced by his advisors—the Mathers, an influential father and son duo of Puritan ministers.

Increase Mather

The father, Increase, had done some important diplomatic work on behalf of the colony. King James in 1686 had not only combined the colonies into the Dominion of New England, he’d deprived them of self government. He’d also put the imperious Anglican Edmund Andros in charge.

Andros lasted less than three years. Armed militia in Massachusetts had sent him back to England. The colony got away with the revolt because the Protestant prince William deposed the Catholic James.

Increase Mather went to London to lobby for a permanent return of democratic government. Phips was there, too, for the same reason.

Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather, then in his mid-20s, served as minister of Boston’s North Church. His father had held the post until he assumed the presidency of Harvard. The younger Mather had baptized William Phips in 1689.

The previous year, an elderly Irish-Catholic cleaning women named Goody Glover had an argument with the children of John Goodwin, one of Cotton Mather’s parishioners. They then began acting strangely. Their father asked Mather to pray for them. He ended up meeting with Goodwin and asking her to repent. She refused, and he accused her of witchcraft.

Mather formally accused Goody Glover of witchcraft during a trial. The judge found her guilty, and she died on the gallows.

Cotton Mather, tough on witchcraft

So when young girls in Salem began to have fits and complain of invisible pinpricks, Cotton Mather knew the devil had enlisted witches to do his work.

Salem

All hell started to break loose on Jan. 20, 1692. In Salem, Mass., Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams began having seizures – just like the Goodwin children. Within a month, they had accused, or “cried out,” Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba for bewitching them.

Four days after the girls first had fits, something terrible happened in York, Maine – the Candlemas Massacre. A French and Indian war party killed or captured about 150 people and burned almost all of their houses.”If York could fall, most towns north of Boston were vulnerable. One of the people they killed was the minister, Shubael Dummer, a distant cousin of future witch trial judge Samuel Sewall. He also had many ties to Essex County.

To Cotton Mather, the death of a Puritan minister meant Satan was winning. To the people of Salem, Satan had arrived in the form of his accomplices.

Over the next four months, more young girls would act strangely and cry out the names of their tormenters. The number of accused would snowball.

Starting To Get Tough on Witchcraft

About five weeks after Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams began having fits, two magistrates got involved. John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin examined the accused, looking for “witches teats” on them. Tituba confessed and eventually named the names of other witches in the conspiracy.

Then over the next few months, four more girls started having fits and accusing others. They “cried out” 27 people, including a four-year-old girl and Salem’s former minister. Hathorne and Corwin examined them, then had them arrested and jailed. Before the first witch trials even started, the first victim, Sarah Osborne, died in prison.

All this time, William Phips was in London with Increase Mather. After Andros had been sent packing, they were trying to get Massachusetts’ original charter back. It restored the elected legislature, but replaced the popularly elected governor with a royal appointee. And William Phips was that royal appointee.

Andros is taken prisoner during the Boston Revolt.

On May 14, Phips and Increase Mather arrived in Boston with a new charter that restored democratic government – sort of – to the colony. It went too far for some, while others thought it didn’t go far enough.

Court of Oyer and Terminer

On May 27, William Phips established the Court of Oyer and Terminer and appointed eight judges. William Stoughton as chief justice, Samuel Sewall, John Richards, Wait Winthrop, Peter Sergeant, Jonathan Corwin, John Hathorne, Bartholomew Gedney and Nathaniel Saltonstall.

All wealthy merchants, they were interrelated and intermarried. Many had speculated heavily in land in Maine, and the war had cost them dearly. Most served as militia officers, and bore some responsibility for recent military losses.

They all believed in witches. And given their recent setbacks, they were primed to get tough on witchcraft.

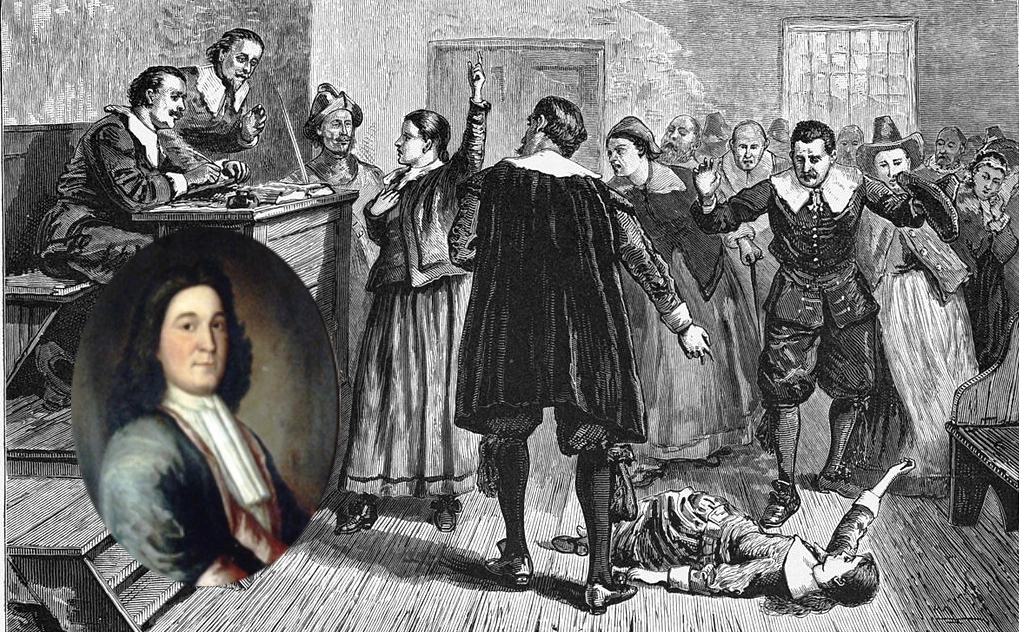

Salem witch trial

Rush to Justice

Six days after Phips created the Court of Oyer and Terminer, the judges found Bridget Bishop guilty of witchcraft and sentenced her to death. Eight days after that, she was hanged on Gallows Hill. Nathaniel Saltonstall quit the court, and Phips replaced him with Jonathan Corwin.

For the next four months, the slaughter continued. Nineteen more were executed, 156 formally accused and 113 imprisoned. Many of those died in the foul prisons. Of 28 people who went to trial, the court found 28 guilty.

The accusations went beyond Salem, to Malden, Topsfield, Marblehead, Billerica, Ipswich, Andover. The judges based many of their guilty verdicts on spectral evidence – the accuser’s dream that a witch would harm her.

In August, a French and Indian raid on Billerica, 25 miles away, killed two families — another victory for Satan.

New Englanders Object

Public support for the witch trials began to fall away.

People wrote letters defending the accused. A group of ministers wrote to Phips and told him people of unblemished reputation, like Rebecca Nurse, had been accused and executed.

Then some of the accusers recanted. The families of the accused discredited the accusers, saying they’d acted out their fits. Two signed petitions went to the General Assembly, complaining the trials had wrongly convicted innocent people with spotless reputations. The petitions also took issue with the use of spectral evidence.

On September 29, William Phips returned from a trip to the Maine frontier, horrified to learn his wife Mary had been cried out as a witch. He found Boston “in a strange ferment of dissatisfaction.” A few days later, Increase Mather denounced the use of spectral evidence. Phips almost immediately banned its use in the trials.

A month after his return from Maine, Phips finally clamped down. He ordered no more arrests, released many accused witches from prison and dismissed the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Then he began the cover-up.

The Cover-Up

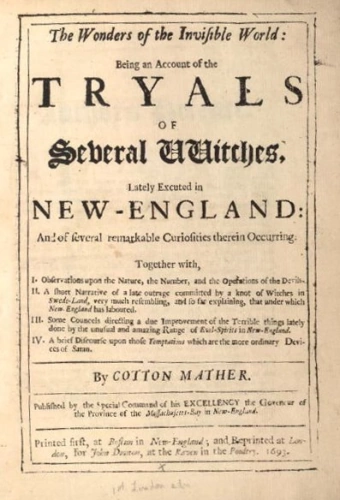

Cotton Mather published a book, More Wonders of the Invisible World, to help Phips out. In it, he whitewashed the witch trials, though he did warn against the use of spectral evidence.

Phips, for his part, claimed he’d been away for most of the trials and didn’t realize what had happened in Salem. He also banned any publication of any account of the witch trials – other than Cotton Mather’s. His fragile government simply wouldn’t survive a public acknowledgment that a court had wrongly executed 20 people and imprisoned many more. As Emerson Baker wrote in Storm of Witchcraft:

“If the state acknowledged the wrongful death or imprisonment of more than 150 innocent citizens, the new government would lose all authority. The king would be forced to recall Governor Phips, the charter could be lost and Massachusetts might end up with another Andros. It would be the end of Massachusetts as a Puritan colony.”

No Longer Tough on Witchcraft

But central to Puritan belief was the requirement that a sinner confess his wrongdoing before God. One witch trial judge, Samuel Sewall, did publicly confess his sin.

Samuel Sewall took the blame and shame

In 1698, Sewall stood before the congregation of the South Church in Boston while the Rev. Samuel Willard, who opposed the witch trials, read his confession. Willard had strongly opposed the Salem witch trials. The confession read:

Samuel Sewall … Desires to take the Blame and shame of it, Asking pardon of men, And especially desiring prayers that God, who has an Unlimited Authority, would pardon that sin and all other his sins; personal and Relative…

Cotton Mather made no such confession, and his memory is forever tainted with his role in the Salem witch trials.

As for William Phips, his suppression of the truth turned the godly City Upon a Hill to a politically expedient government, wrote Baker. It created distrust between the legislature and the royal governor, an animosity that would last until 1775.

William Phips pardoned everyone left who’d been accused of witchcraft. He died on Feb. 18, 1695.

This story last updated in 2023.