Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake Hallett started the first scandal in Greenwich, Conn., over – what else? – infidelity and real estate.

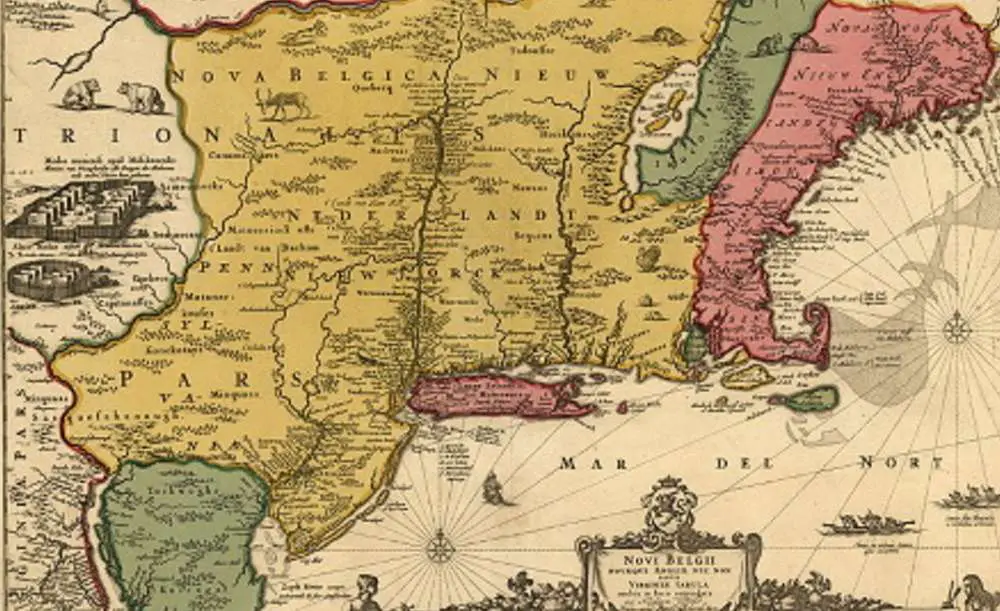

The scandal put her in the midst of a border dispute between the Dutch in New Netherlands and the Puritan English in New Haven Colony.

It was the middle of the 17th century, and Greenwich was a howling wilderness on the edge of the Puritan colonies. When Elizabeth began living with a man allegedly not her husband, the Puritans could have hanged her for adultery.

But over the course of her eventful lifetime, she found protection from her powerful relatives—Uncle John, governor of Massachusetts Bay, and Cousin John, Jr., eventually governor of Connecticut.

The Winthrop men probably sympathized with the 30-something mother of six. She had a mentally ill husband and lived under constant threat by Indians, armed Dutchmen and vengeful Puritan theocrats.

Elizabeth Fones

Her life didn’t start out as an adventure. She was the daughter of a prosperous, staunchly Puritan family. She was born in Groton Manor in 1610 to Thomas Fones, a pharmacist, and Anne Winthrop, sister to John Winthrop. Anne Winthrop died when Elizabeth was just 11, and she and her sister Martha helped out in her father’s apothecary. They mixed medicines, ordered supplies and made deliveries around town.

When Elizabeth reached her late teens their wayward cousin, Henry Winthrop, came to live with them. John Winthrop, despairing of his son, had asked if Henry could live in the regulated Fones household after his return from a failed business trip. Thomas Fones, to his regret, said ‘yes.’

Henry drank, gambled, joked and made friends with papists. Elizabeth thought the reckless and undisciplined young man was terrific. Soon they decided to marry. Her father, tired of covering Henry’s gambling debts, didn’t approve.

They tied the knot in a wedding described as ‘tedious’ on April 25, 1629. Two weeks later, Thomas Fones died.

Elizabeth’s sister Martha made a more sensible match, marrying Henry’s serious brother, John Winthrop, Jr.

Two years later, Henry sailed with his father to North America in the Great Puritan Migration. Elizabeth, pregnant with their first child, stayed behind.

Tragedy No. 1

Henry never saw his child. On the day after his ship arrived in the New World, he and some others decided to explore. He spotted a canoe across a river and he tried to swim to it. Halfway across, severe cramps seized him and he drowned.

“My son Henry, my son Henry, ah my poor child,” wrote John Winthrop.

Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake

John Winthrop then urged Elizabeth and his new granddaughter, Martha Johana Winthrop, to sail to Massachusetts and join him. And so they did.

Her prospects seemed to brighten in the New World, where her uncle arranged her marriage to Roger Feake, a mild-mannered, devout goldsmith.

The couple moved to Watertown, Mass., where they began to acquire large parcels of land. Robert served as selectman and as lieutenant in the local militia. His captain, Daniel Patrick, was a blustery, uncouth womanizer with a Dutch wife. Patrick would play a large role in Elizabeth’s life.

Robert and Elizabeth Fones Feake lived in Watertown for nine years, and Elizabeth had three more children.

In 1636, Robert and Elizabeth Feake wrote to John Winthrop, Jr., in Connecticut telling them they planned to move to Wethersfield (then known as Watertown). They were no longer in-laws, as her sister, Martha, had died and Winthrop had remarried. But they were still cousins.

Their plans to move to Wethersfield fell through, as the Pequot War broke out. So instead, for reasons unknown, Elizabeth and Robert Feake, along with their growing family, followed Daniel Patrick to the deep wilderness of southwestern Connecticut.

Patrick may have wanted to leave Massachusetts after the Puritans imposed humiliating punishments for his sexual escapades. Patrick had a Dutch wife and had served with the Dutch military, so perhaps he wanted to be near Dutch New Amsterda. Now New York City, it was then the seat of government for Dutch New Netherlands.

Whatever the case, it was a bad move.

Geography Is Destiny

Greenwich wasn’t exactly in the middle of nowhere. In fact, it was smack in the middle of two colonies (Dutch New Netherlands and New Haven) and an unincorporated settlement. All three wanted it.

It was located just southwest of Stamford, an independent Puritan settlement of about 58 houses. Stamford lay beyond the jurisdiction of the New Haven Colony, whose leaders didn’t claim Stamford for fear of provoking a war with New Netherlands.

In 1640, the Feakes and the Patricks arrived in a small boat in what is now Old Greenwich. The couples then exchanged 20 coats for land with the local Indians—but they only honored the deal with 11 coats.

Elizabeth bought her own, separate piece of property. For more than a century people called it Elizabeth’s Neck.

The Indians viewed the transaction as more of a rental than a purchase, permission to use the land. The English, of course, viewed it as a transfer of property. As usual, that caused problems.

Groenwits

From the start, threats from Indians and the nearby Dutch plagued the two families. So Daniel Patrick and Elizabeth – not Robert – Feake pledged their loyalty to the Dutch in 1642. Robert Feake, described as ‘now sick,’ may have been too far gone to sign it himself.

Greenwich became Groenwits, and it served as the eastern border of New Netherlands.

Elizabeth and Robert Feake had two more children, which they had baptized in New Amsterdam.

Mental Illness

To some of her contemporaries, Elizabeth was a grasping, amoral woman who drove her meek husband crazy by thoroughly dominating him.

Missy Wolfe, in Insubordinate Spirit, wrote that testimony about Robert Feake’s state of mind included a damning statement: “He exhibited a more than ordinary respect towards his late wife, and that he in our opinion was more easily to be seduced by her to do whatever she wished, than what was wise and reasonable.”

According to others, the hapless Feake couldn’t do much at all.

Robert Feake was described as ‘unfit to dispose a plantation’ and ‘unsettled and troubled in his understanding and his brain.’ Several witnesses testified that Robert Feake’s ‘God-fearing heart was so absorbed with spiritual and heavenly things that he little thought of the things of this life, and took neither heed nor care of what was tendered to his external property.’

William Hallett

In 1643, a Dutch soldier murdered Daniel Patrick. Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake and Daniel Patrick’s widow Anneke were left with 11 children to raise in the otherwise unpopulated settlement. Tensions were rising between the Indians and the Europeans. In March 1644 a mixed force of English and Dutch would massacre 500 Indians just 15 miles away. The English in Stamford couldn’t or wouldn’t protect the two families in Greenwich. And Elizabeth found her husband completely useless.

At some point an Englishman named William Hallett showed up in Greenwich. How and exactly when isn’t clear.

But Hallett was neither foolish nor crazy like Elizabeth’s husbands. In fact, he was smart and able. And with permission from the addled Robert Feake, Hallett moved in and took over management of his property. Feake, however, never made his intentions completely clear about what he wanted done with his property.

Elizabeth now found herself vulnerable to the English colonists in Stamford, who had an eye on her Greenwich real estate. So did New Haven Colony.

With Relatives Like These

Two ambitious young men—her son-in-law and her husband’s nephew—handed the Puritan magistrates the tools to seize her property.

In 1646, Thomas Lyon married Elizabeth’s frail 16-year-old daughter, Martha Johana Winthrop. And Tobias Feake, Robert’s nephew, married Daniel Patrick’s widow. Then Elizabeth Feake and William Hallett tried to sell a piece of property jointly owned by Robert Feake and Daniel Patrick.

Thomas Lyon and Tobias Feake viewed that property as theirs. They began to spread salacious rumors about Elizabeth and William, claiming they had no right to sell the land. Lyon had moved into the Feake household, and wrote a letter to John Winthrop, his wife’s grandfather, claiming William had gotten Elizabeth pregnant. He also wrote to the English authorities in the New Haven Colony.

Tobias Feake chimed in with the claim that William Hallett did not have a legitimate right to sell the property.

The magistrates in Stamford issued an edict: If Elizabeth wanted to stay in Greenwich and keep her property, William Hallett would have to leave. If she left Greenwich, the Puritan authorities in Stamford would seize her children and her real estate.

Never mind that the English magistrates had no jurisdiction over Dutch Greenwich. And that Elizabeth had divorced Robert Feake and married William Hallett.

Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake Hallett

In March 1647, Robert Feake left Greenwich. He made over his property and half his cash to Elizabeth and William, and left for England.

On April 14, 1647, Elizabeth sailed to New Amsterdam to baptize her youngest Feake child, Sarah. She also got a Dutch divorce on the grounds of her adultery. And then she married William Hallett.

Where Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake Hallett got married is a matter of speculation. One of William Hallett’s descendants claims four possibilities:

- At New Amsterdam in the Church on the Fort by the pastor in 1647.

- At New Amsterdam by the Dutch Governor, Willem Kieft in 1647.

- In Greenwich by William Hallett, magistrate (Hallett was a Dutch official with the power to marry) in 1647.

- At New London by John Winthrop, Jr., in 1648.

John Winthrop, Jr., had stature among Puritans in what is now Connecticut. By 1648 he had already served as governor of the New Saybrook Colony. He would eventually serve as governor of the Connecticut Colony and play a big role in merging the disparate settlements into one.

In July 1648, the governor of New Haven Colony, Theophilus Eaton, told John Winthrop, Jr., that he had directed William Hallett to settle his messy affairs in the English, not the Dutch, courts. Winthrop also found out the Connecticut Colony (then separate from New Haven) ordered the Halletts arrested. The magistrates in Hartford wanted them to appear before them to answer charges of adultery in Connecticut.

Taking Flight

Elizabeth and William Hallett did not intend to comply. Instead, they had already spirited away from Greenwich their children, two cows and their household possessions. They found sanctuary in New London, with Cousin John Winthrop, Jr.

Missy Wolfe in Insubordinate Spirit argues that John Winthrop, Jr., engineered Elizabeth’s divorce and remarriage. As a devout Puritan, he would have had no problem with divorce. Puritans allowed, though rarely, escape from the chains of matrimony, because they viewed it as a civil matter.

Peter Stuyvesant took over as director of New Amsterdam in 1647 and seized the Feake-Patrick-Hallett property. Cousin John Winthrop negotiated with him to let the Halletts return to Greenwich to work their land. Finally in 1649 they did return.

Elizabeth wrote a profuse letter of thanks to her cousin, explaining they had finally settled their real estate issues with Robert Feake. He had returned from England and resettled in Watertown.

More Trouble

But the Halletts wouldn’t stay long in Greenwich. The English and the Dutch entered into the Treaty of Hartford in 1650. It created a hard boundary between Connecticut and New York. The treaty reflected diminished Dutch strength vis-à-vis the English. But much of Greenwich, including the Hallett’s property, still lay within Dutch jurisdiction, to the vast annoyance of the New Haven Colony leaders.

The Puritan colonies continued to try to take over Greenwich. Eventually New Haven colony did succeed in absorbing Greenwich.

The Halletts, though, depended on the Dutch for protection from English prosecution. In 1650, the Connecticut Colony issued another arrest warrant for the Halletts.

A year after they returned to Greenwich, they moved deeper into Dutch territory on Long Island, across the East River from Gracie Mansion. Their land—12 acres granted by Peter Stuyvesant–is in present day Astoria near Hellgate.

They sold the rest of their Greenwich property to an Englishman.

New Amsterdam

In New Amsterdam, the Halletts survived an Indian attack and the wrath of Peter Stuyvesant. Perhaps their experience with the Connecticut Puritans had soured them on the religion. Eventually they found the Quaker Way. Stuyvesant, a firm Dutch Reformed Church member, tried to banish them.

Over time, William and Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake Hallett amassed a 2,200-acre plantation in Astoria from Bowery Bay to Sunswick Creek.

Elizabeth Fones Winthrop Feake Hallett died in the early 1670s. Her descendants include the painter Robert Feke and Robert Bowne, who started a publishing company that until 2010 was the oldest publicly traded company in the United States.

The End of Robert Feake

Feake in 1647 sailed to England, where he received a pardon from the House of Commons in March 1650 for an unspecified crime,

Then he returned to Watertown in 1650.

By 1660, his mental illness had reached such a stage that the Town of Watertown took care of him. He died in 1663 at the home of Deacon Samuel Thatcher.

With thanks to Insubordinate Spirit: A True Story of Life and Loss in Earliest America 1610-1665 by Missy Wolf and to Roger Thompson in Divided We Stand: Watertown, Massachusetts, 1630-1680.

Images: Images: Thomas Lyon House, By Joshua Koerner – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28725770. This story was updated in 2024.