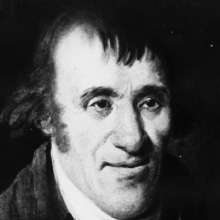

Today we’d call it torture, but when the British tortured Ethan Allen in prison they called it ‘harsh treatment.’

On Sept. 25, 1775, British troops captured Allen, a Continental Army colonel, when he retreated from a poorly planned attack on Montreal. They seemed delighted at the downfall of the man who captured Fort Ticonderoga.

Ethan Allen then spent more than two years as a prisoner of war.

During the American Revolution it was no small matter to be taken prisoner by the British. More revolutionaries died as prisoners of war than on the battlefield.

How the British Tortured Allen

From the beginning the British tortured Allen psychologically as well as physically. They often confined him with privates, though he considered himself an officer and a gentleman. They also threatened to hang him in England.

Gen. Richard Prescott hurled a typical insult at Ethan Allen upon his capture:

I shall not execute you now; but you shall grace a halter at Tyburn, God damn you.

They took him to the Gaspee schooner of war and bound his hands and feet in irons. His leg irons weighed 30 pounds and consisted of an eight-foot long iron bar and the irons shut tight around his ankles. He could only sleep on his back.

He sat on a chest, days and most nights, guarded round the clock by men with bayonets. They refused to loosen his shackles. Sailors came below to insult him.

Ethan Allen won a brief reprieve, when he spent a little more than a week on another vessel under a British captain who treated him well. Then the British tortured him again by herding him aboard the Adamant.

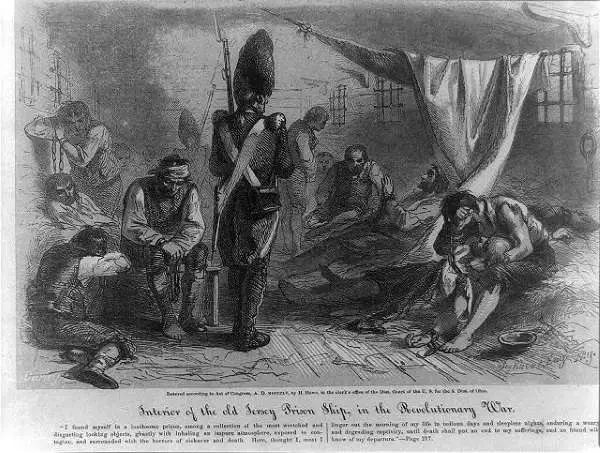

During the 40-day voyage to England, Allen and 33 other prisoners were confined in a small enclosure, 20 feet by 22 feet. It had two excrement tubs. Not only were they to eat in those cramped and filthy quarters, Allen reported, ‘but every blackguard sailor and tory aboard insulted them.’ One lieutenant spat in his face as he was herded into the small space. Allen partly knocked him down despite his handcuffs.

Aboard the Adamant

Allen wrote that the British tortured the prisoners by giving them only a small amount of water, though the men all came down with diarrhea and fever. The enclosure had no light, so the prisoners couldn’t see each other, and lice covered all their bodies. They only survived, wrote Allen, because the British gave them rum.

After 40 days they arrived in Falmouth, England, and finally saw sunshine and breathed fresh air. Crowds came to see them, and Ethan Allen was self-conscious about his outfit. He wore a short fawn hunting jacket, twill breeches and a red cap. The English had never seen anything quite like it and gawked at him.

He didn’t know it at the time, but Parliament debated his fate, and decided against executing him for treason. They reasoned the Americans might retaliate against the many British prisoners they held.

The British authorities confined him in close quarters in a castle, where he received much better treatment. He ate well and had a bottle of wine delivered to him every day. Still, he anticipated a cruel death by hanging.

Back in America

After about two weeks, The British decided to send him back to America as a prisoner of war. With about three dozen other prisoners he boarded the frigate Solebay and sailed to Cork in Ireland. There, generous Irishmen – no fans of the English — gave the prisoners clothing and stores of food.

After arriving in Cape Fear, N.C., the prisoners boarded another ship bound for Halifax. They received little food and no medical treatment for the scurvy.

Ethan Allen survived the scurvy, which afflicted him but little. In Halifax, however, he was locked in a room with the other prisoners and excrement tubs. There he grew sick and weak and couldn’t eat.

His situation improved when the British sent him to New York. Eventually they paroled him, limiting him to the city.

More POWs

New York’s churches were filled with American prisoners, captured after Washington’s defeat on Long Island. As the Continental Army retreated across New Jersey, Ethan Allen visited the American prisoners. The British tortured them too, promising better treatment if they enlisted in the British Army.

The prisoners had only small portions of moldy bread and bad meat to eat. Many starved to death, and 2,000 ultimately died of hunger, cold and sickness. Allen saw the dead lying in their own excrement.

When Gen. John Burgoyne retook Ticonderoga, the British retook Ethan Allen. They seized him in a tavern, claimed he violated parole and confined him in a dungeon from Aug. 26, 1777, to May 3, 1778.

Finally, the British exchanged him for Archibald Campbell, and he returned to Bennington where his Green Mountain Boays thought he had died.

They celebrated by firing off three cannon upon his return and 14 the next day, 13 for the colonies and one for Young Vermont.

And then they ‘passed a flowing bowl’ in celebration.

With thanks to A Narrative of Ethan Allen’s Captivity, by Ethan Allen. This story was updated in 2022.

4 comments

Allen’s transport conditions to England still better than the plight of enslaved Africans who’s inhuman conditions were perpetrated by English and American merchants of the era.

We’re curious as to why so many people comment that African-Americans suffered more than anyone on stories that aren’t really related to slavery. Is it a product of today’s identity politics?

[…] Heroes, might have left a more brilliant specimen of talent and learning. Many have moved in a higher sphere of action, who have left no record of their toils and privations behind them – but we venture to assert, that […]

[…] loaded hundreds of starving prisoners onto transport ships. Some couldn’t make it that far. Ethan Allen, on parole himself, saw several prisoners fall dead in the streets as they tried to walk to the […]

Comments are closed.