The American Civil War was first and foremost a clash between Americans in the North and the South. But it still attracted a large contingent of foreign nationals, fighting for both sides. German, Irish, English, Scots, Welsh, Polish,  French, Italian, Scandinavian, Canadian, Mexicans, Hawaiians, Native Americans and even Chinese joined the fight. Most, but not all, fought for the Union. The names and stories of men like Joseph Pierce tend to get pushed aside in the narrative of a war fought, after all, over the issue of slavery.

French, Italian, Scandinavian, Canadian, Mexicans, Hawaiians, Native Americans and even Chinese joined the fight. Most, but not all, fought for the Union. The names and stories of men like Joseph Pierce tend to get pushed aside in the narrative of a war fought, after all, over the issue of slavery.

Joseph Pierce was born about 1842 in Guangdong, Qing Empire (modern China). However, both his real name, and the exact date of his birth are unknown. Pierce himself claimed his birth date as Nov. 16, 1842. What is known about his early life begins in 1853 when an American ship captain from Berlin, Conn., named Amos Peck somehow “acquired” him. He either paid the boy’s father $6 or the paid boy’s older brother considerably more.

The trade in “coolie” labor (literally “bitter labor”) had reached its height at the time. In 1855, the British and Chinese governments banned the trade. They left it, not surprisingly, to the slave-trading United States to dominate it. Probably the family viewed the boy as an added burden, and they saw a way to ease the burden and get some needed money.

Becoming Joseph Pierce

While the buying and selling of human beings is slavery, that was not to be the case for the young Chinese. Exactly why Captain Peck took the boy is not known. But what is clear is that the relationship was not one of master and slave or indentured servant.

Given Captain Peck’s future conduct, it is clear that he saw it his duty to “rescue” the boy and offer him a better life. The 9-10-year-old Chinese boy joined the ship’s crew – not all that unusual for a boy of that age. Probably because the crew could not pronounce his name, they took to calling him “Joe,” and by default that became his first name. His last name, “Pierce,” apparently evolved from the fact that Franklin Pierce served as president of the United States in 1853.

When Captain Peck and the now Joseph Pierce arrived back in Connecticut, the family treated Joseph not as a possession but as one of them. He attended school and went to church with the family.

The United States had no immigration laws during most of the 19th century in America, and the individual states mostly decided on citizenship status.

All in the Family

There is no indication that Pierce had any real problems integrating into the Connecticut society in Berlin. Peck, still a ship’s captain, left for long periods on voyages. If Pierce was to be accepted or rejected as a family member, these long absences offered an opportunity for either one. But Peck’s wife Eliza, took, Joseph into the fold. She taught him to read and write. Along with the rest of his new brothers and sisters, she sent him to school.

Interestingly, Peck’s voyages to China kept him involved in the coolie trade. However, he was swiftly becoming disgusted by its brutality. In fact, the only real difference between the African slave trade and the coolie trade was the color of the skin of the “cargo.”

Pvt. Joseph Pierce

When the Civil War began in 1861, Joseph Pierce was now about 19 years old and thoroughly Americanized. He undoubtedly would have followed the progress of the fighting. Most likely he would have seen at least a couple of the young men he knew enlist. Then on Aug. 23, 1862, the 14th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment mustered at Camp Foot near Hartford. On Aug. 26, 1862, Joseph Pierce enlisted in the regiment at New Britain, in Company F, as a private for a three-year term. At the time of his enlistment, he was described as 5’ 5” tall, with dark hair, black eyes and, not surprisingly, a dark complexion. When Pierce enlisted, the 14th Connecticut had already left for Washington, D.C., and he would have joined them there.

It should be remembered that in 1862, Blacks were not allowed to fight for the Union. The Union Army was white. But since Pierce joined along with other men and friends from the Berlin area, he would have been already accepted as part of the community and his origin overlooked.

Antietam

Less than a month later, on Sept. 16-17, 1862, the largely untrained 14th Connecticut and Joseph Pierce fought in the bloodbath at Antietam in its baptism of fire. The regiment’s monument at Antietam describes the action:

Advanced to this point in a charge about 9:30 A.M., September 17th , 1862, then fell back eighty-eight yards to the cornfield fence and held position heavily engaged nearly two hour; then was sent to the support of the first brigade of its division at the Roulette Lane two hours; then was sent to the extreme left of the first division of this Corps to the support of Brooke’s Brigade and at 5 P. M. was placed in support between the Brigades of Caldwell and Meagher of that Division overlooking ‘Bloody Lane,’ holding position here until 10 A. M. of the 18th when relieved.

At Antietam, the regiment lost 38 killed, 88 wounded and 21 missing. Antietam saw the greatest loss of American lives in a single day in history. It was a rude awakening to Joseph and the men of the 14th Connecticut to the realities of war. During the battle, Joseph fell while climbing over a fence, injuring his back. Sent to a Union hospital in Alexandria, Va., he stayed there off and on. At some point he worked as a hospital orderly. Then in May 1863, he rejoined his regiment, probably in time to participate in the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 1-5, 1863.

From Chancellorsville, the Army of the Potomac, including Pierce and the 14th Connecticut, began the Gettysburg Campaign. They followed Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia north into Pennsylvania. The regiment arrived at Gettysburg on the evening of July 1, 1863 and went into line on Cemetery Ridge. Of the over 1,000 men who marched out of Connecticut in August 1862, only about 160 men were present for duty at Gettysburg less than a year later.

Gettysburg

About halfway between the Union line on Cemetery Ridge and the Confederate line on what is now Confederate Avenue, sat the 60-acre William & Adelina Bliss Farm. It did not take long for Confederate pickets to occupy the farmhouse and barn and begin serious sniping on the Union Line. The farm would change hands three times over the next day and a half as both sides tried to push the other back. Eventually, on the morning of July 3, the 14th Maine was ordered to take and hold the barn and house. But shortly after the order was given, it was modified, to allow them to burn the house and barn if it got too “hot.”

However the regiment had now charged several hundred yards under fire and had retaken the area, driving the Confederates back into the farm orchard. The first messenger with the new order was wounded. A second messenger, Sgt. Charles Hitchcock of the 11th New York, made his way through a gauntlet of fire with orders to torch everything. By now, the 14th Connecticut had discovered why it was so difficult to hold on to the buildings. The barn was poorly sited to take the house under effective fire with no firing ports facing the house, and the house itself was more a bullet sieve than a place of cover.

Getting the new order, the regiment put the house and the barn to the torch and fell back to their line on Cemetery Ridge under rifle and cannon fire, taking their 20 dead and wounded with them. The respite would be short lived since sometime after noon – no one knows the exact time – the Confederates started their bombardment of Cemetery Ridge in prelude to the grand charge.

A Soldier of Commendable Bravery

An article written by Chenyu Zhang, entitled “’A Soldier of Commendable Bravery and Pluck:’ Joseph Pierce’s Struggle for Citizenship” describes his actions at Gettysburg as follows:

Pierce went out first on the skirmish line on July 2, and volunteered for the attack on the Bliss farm on July 3. Upon capturing the Bliss farm, Pierce and his men struggled to capture the house as the rear of the barn provided no openings to shoot from. ‘[The men] had received orders to capture the buildings ‘to stay’ and the faithful men know no other course than to obey commands’ The detail returned triumphant with the building set aflame behind them…The day was far from over and Pierce would help repulse Pickett’s Charge…

For Pierce and the Union soldiers all along Cemetery Ridge, waiting for an attack that all knew was coming would have been a form of mental torture. Over 100 Confederate guns began a two-hour bombardment of the Union line, primarily aimed at Union gun positions. Fortunately for the Union, the Confederate artillery was badly manned and aimed. Most rounds were fired high. This, of course, was hindsight for the Union soldiers. So, at the time, the fear would have been very palpable when they had to sit for two hours listening to the deafening roar and crash of shells, unable to respond.

The 14th Connecticut

Joseph Pierce would have manned the low wall protecting the men of the 14th Connecticut as they huddled under the incessant Confederate cannon fire. It lifted as 12,000 Confederate troops began the mile-long charge wrongly referred to as Picket’s Charge. Picket’s Division was just one of several Confederate divisions involved, and the 14th Connecticut would fight on the right of the Union line. That included fighting elements of the 13th Alabama, 26th North Carolina and 14th Tennessee Regiments.

Zhang’s article goes on to say:

…Pierce ‘carefully stuffed his long queue down the back of his dirty uniform shirt and pulled lightly on the breech of his Sharp’s to double check its load.’ The breech-loading Sharp’s rifles allowed Pierce and his men to fire ‘so rapidly that the barrels became to hot to use, and they poured precious water from their canteens to cool the barrel.’ The Confederate lines broke quicker in front of Pierce’s regiment than anywhere else,…

Monuments to 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment (dedicated in 1884), 1st Massachusetts Sharp Shooters (dedicated 1886) and 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery (dedicated 1886) with other monuments in background on Hancock Avenue, at Gettysburg

The monument for the 14th Connecticut at Gettysburg states the following:

“The 1th C.V reached the vicinity of Gettysburg at evening July 1st, 1863, and held this position [on Cemetery Ridge] July 2nd, 3rd and 4th. The regt. took part in the repulse of Longstreet’s grand charge on the 3rd, capturing in their immediate front more than 200 prisoners and five battle-flags. They also, on the 3rd, captured from the enemy’s sharp-shooters the Bliss buildings in their far front, and held them until ordered to burn them. Men in action 160, killed and wounded 62.”

Cpl. Joseph Pierce

Fewer than 100 men were fit for duty on the morning of July 4 when the Confederates retreated. Joseph Pierce was one of the lucky ones.

When the fight ended, Pierce and other men were detailed to tend to the Confederate wounded lying in front of their position. The regiment held the position for one more night until it was evident that Lee had retreated. Then began a three-month movement following Lee back into Virginia. The 14th Connecticut saw minor action in the Bristoe Campaign on Oct. 9-22, 1863. It also saw some action in the Mine Run Campaign of Nov. 26-Dec. 2, 1863. Then the regiment went into winter quarters at Stoney Mountain, Va.

In the midst of all this, Joseph Pierce won promotion to corporal on Nov. 1, 1863.

When the war started, rank was generally more of a popular affair than one of skill and competence. By this stage of the war however, rank, particularly enlisted rank, almost always went to the ones most qualified to hold it. The rank of corporal is a leadership rank. Pierce’s promotion says much of his ability, leadership and courage under fire. It also clearly indicates racial prejudice was not an issue in the 14th Connecticut. It was the highest rank of any of the approximately 50 Chinese that served in the Civil War.

The Face of the Army

Then in February 1864, Corporal Pierce came down with acute rheumatism. The condition is described as: “…characterized by swelling, tenderness, and redness of many joints of the body. It is a part of rheumatic fever. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a similar condition that happens when the immune system attacks your own tissues and causes joint pain, swelling, and stiffness.” Sickness in various forms was a staple of Civil War camp life, and a greater killer and disabler than combat. Acute rheumatism would have made it almost impossible for Pierce to continue active campaigning. On Feb. 29, 1864, he was sent on recruiting duty, presumably back to Connecticut to refill the depleted ranks of the regiment. Again, Zhang notes: “On recruiting duty, Pierce became the face of the Union Army and the United States.”

Since by this time, the 14th Connecticut was in great need of new blood, the fact that Pierce was trusted as a recruiter speaks volumes for the regiments respect for his character over his color and origin.

Apparently, Pierce rejoined the 14th Connecticut in time to participate in Grant’s Overland Campaign. Pierce’s record is unclear after his return, but the 14th Connecticut fought in a series of fierce battles including the Battle of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Totopotomoy, and Cold Harbor. The regiment then went on to take part in the First Assault on Petersburg on June 15-18, 1864, and in many of the battles that evolved around the Siege of Petersburg until April 2, 1865, culminating in the assault and fall of Petersburg. Pierce and the 14th Connecticut took part in the Appomattox Campaign and were present on April 9, 1865 when Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House.

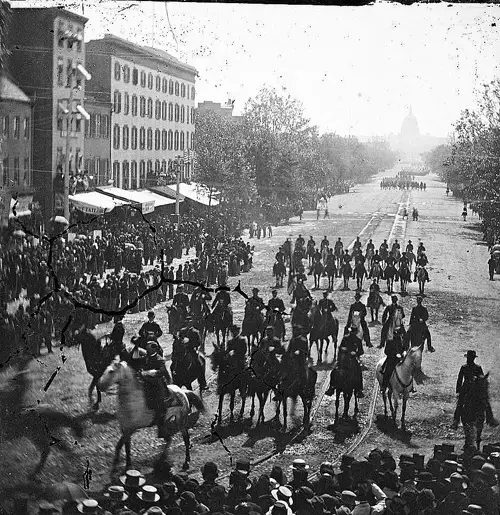

The Grand Review

After the surrender, the regiment moved north, leading the 2nd Corps of the Army of the Potomac as it left Petersburg, marching through Richmond enroute to Washington, D.C. On May 23, 1865, Pierce and the 14th Connecticut took part in the Grand Review when 145,000 Union soldiers marched from the U.S. Capitol to the White House in celebration of their victory.

Cpl. Joseph Pierce mustered out on either May 30 or 31, 1865. He then traveled with the regiment to Hartford, where the army formally released them from service. A civilian once again, Joseph returned to the land and took up farming for a short time in New Britain. Sometime between 1865 and 1868 he became a naturalized citizen. Farming didn’t last long, and in 1868 he the New Britain Excise Tax List described him as a “peddler.” Another source indicates that he moved to Meriden and learned the trade of silver engraving over the next two years. He followed that profession for the rest of his life.

Life for Joseph Pierce maintained a normal pace, unhindered by his race. Described by his friends and neighbors as very fashionable, a picture from the time shows a handsome young man immaculately dressed. He still had his distinctive pigtail. Keeping the pigtail clearly indicates that he did not attempt to hide his origins.

Sometime around 1875-early 1876, Pierce became acquainted with Martha A. Morgan, an 18-year-old American girl from Portland, Conn. And on Nov. 12, 1876, the Reverand R. S. Eldridge of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Branford married the couple. The union would produce two daughters and two sons.

Chinese Exclusion Act

Reflecting more current times, anti-immigration and racism again raised its ugly head in 1882. Congress that year passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Coolie Prohibition Act had been passed in 1862, meant at the time as an adjunct to anti-slavery acts since coolies were seen as forced labor. But it had not stopped Chinese from freely immigrating after the war. This large influx of Chinese now was seen as a problem. Up to 1882, the federal government did not control immigration, leaving it up to the states.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the real start of a federal immigration system. The act was callously effective and basically stopped Chinese from entering the country for decades. In 1892 the act was broadened to require “certificates of residency,” the precursor to green cards, that required all Chinese, including naturalized Chinese, to register. For Joseph Pierce, it set a dangerous precedent, and a pretense reflected in modern times. Zhang’s article notes: “In 1894, four newspapers, including one from as far as Arizona territory, reported on Pierce’s fear of deportation. The New York Tribune states the following:

Joseph Piece, and American citizen of Meriden, Conn., has been in this country since he was 10 years old, served through the Civil War, and is now on the pension rolls, but as he was born in Canton, China, he has been ordered by the Internal Revenue Collector of Meriden to register as a Chinaman, under the Geray Act. Jospeh naturally objects, as he fears his registration may lead to deportation after May 1.”

Unlike modern times, however, Joseph’s adopted community rallied behind him and supported him. By 1900, the Meriden residents had convinced the federal government that Joseph was actually Japanese. The 1900 and 1910 census records reflect that, and list all his family as “white.”

Joseph Pierce, Proud Veteran

Joseph Pierce remained proud of his Civil War service for the rest of his life, attending several veterans’ reunions. Zhang’s paper states regarding one veteran’s reunion: “‘Joe’ was a great favorite with us, as was evident from the hearty, vociferous round of applause with which he was greeted by the boys as he entered the hall at our recent meeting, his bright eyes snapping and sparkling in his honest face as they were wont to years ago.”

Illness plagued Joseph’s last years. So, in 1907, he petitioned to increase his 1890 Civil War Service pension due to his medical problems. He died on Jan. 3, 1916, from influenza compounded by chronic bronchitis and the arteriosclerosis that had troubled him since 1864. He was buried in the Walnut Grove Cemetery in Meriden, Conn.

Joseph’s wife, Martha Morgan Pierce, died in 1926. The couple’s son Franklin Norris Pierce was born in 1882 and died in 1952. Their second son, Howard Benjamin Pierce, was born in 1884 and died in 1959. Their daughter Lula Edna Pierce’s birthdate in unknown but she died very young in 1895. Little is known about a fourth daughter, Edna Berta Pierce. It would appear that neither of the sons married.

Images: Monuments Mumper & Co, photographer. Monuments to 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment dedicated in , 1st Massachusetts Sharp Shooters dedicated 1886 and 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery dedicated 1886 with other monuments in background on Hancock Avenue, at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania / Mumper & Co., Gettysburg, Pa. Gettysburg United States Pennsylvania, None. [Gettysburg, pa.: mumper & co., between 1886 and 1900] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2024640868/.

Union Line on Cemetery Ridge:(ca. 1887) Battle of Gettysburg. , ca. 1887. May 16. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003663828/.