In 1951, Boston Evening Traveler columnist Walter Schofield began campaigning for the city to create a path taking pedestrians past milestones of the American Revolution. By May, Mayor John Hynes bowed to the pressure and agreed to establish the Freedom Trail. Two young men — Malcolm X and Martin Luther King — took note.

Malcolm Little was incarcerated in the Norfolk Prison Colony that year. Martin Luther King was just settling in to his St. Botolph Street apartment as he began doctoral studies at Boston University.

The history of Boston’s fight for freedom cannot have been lost on them. Their rhetoric centered on freedom. “I believe in a religion that believes in freedom,” said Malcolm X. “Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,” wrote Martin from Birmingham Jail.

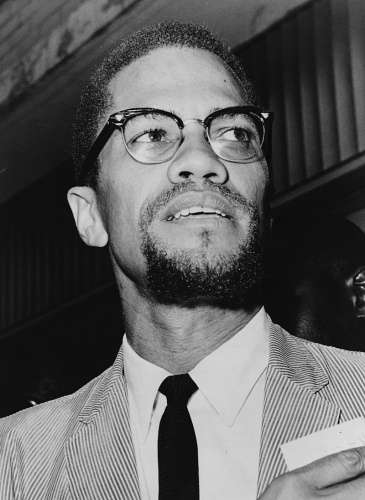

Malcolm X and Martin Luther King

But religion, not revolution, marked the path of liberation for these two deeply spiritual men. Boston turned Malcolm Little into Malcolm X when he left in the summer of 1952. Boston turned Martin Luther King into Dr. King when he left for Montgomery, Ala., in 1954. There he had a job as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

Within 18 months, Martin would rocket to the center of the international stage as a leader of the Montgomery bus boycott. For Malcolm, fame would take longer. He would attract a large following to the Nation of Islam. But not until 1959 did he attract much attention beyond the black community.

White people found Martin’s pacifist, integrationist religion far more palatable than Malcolm’s muscular Islam. By 1957, Time put Martin Luther King on the cover of Time and Meet the Press. interviewed him on television. Prime time wasn’t ready for Malcolm’s message of black independence, pride and entrepreneurialism within the African-American community.

Together they would play good cop, bad cop in the struggle to lift up American blacks. They learned how to do it in Boston.

The Cradle of Freedom

Both men immersed themselves in the city’s culture of scholarship and debate, even if for Malcolm that meant the Norfolk Prison Colony’s library and debating society. Martin was cocooned in a white, liberal school of theology that welcomed black scholars. Malcolm studied the literature of slavery in an extraordinary prison library.

Both men acknowledge the influence Boston had on them. Malcolm wrote in his autobiography, “No physical move in my life has been more pivotal or profound in its repercussions.” Martin often referred to Boston as his second home.

Martin at BU

Boston must have been exciting for a young doctoral student from the Deep South. He had never lived in a multicultural, mixed neighborhood like Boston’s South End. That’s what Martin found at 170 St. Botolph St. for his first few months in Boston, and then at 397 Massachusetts Ave., in the middle of this first year at BU. It must have also been a heady experience to debate with world-famous religious philosophers like Edgar Brightman.

In the ‘40s and ‘50s, Boston University was a center of liberal theological thought. It welcomed African-American graduate students. Brightman led the school of theology known as Boston Personalism. From Boston Personalism, Martin derived two tenets of his thought: belief in a personal God and belief in the dignity of all mankind.

Marsh Chapel.

In his final year at Boston University, King family friend Howard Thurman became dean of BU’s Marsh Chapel, the first African-American dean of a predominately white university. An internationally known theologian, he knew Gandhi. He became Martin’s spiritual advisor. Martin was said to have carried until his death Thurman’s book Jesus and the Disinherited. The book shows how to use the Gospel as a guide to resistance for the poor and disenfranchised.

The Parkhurst Collection

A very different institution had a profound influence on Malcolm: The Parkhurst collection at the Norfolk Prison Colony’s library. In 1946, Lewis Parkhurst, a successful Unitarian lawmaker and publisher, had bequeathed his books to the prison. The collection had so many books that some were still in crates when Malcolm was transferred to Norfolk in 1948.

The Parkhurst collection included anti-slavery pamphlets and books, including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It also had the writings of Frederick Law Olmsted — probably The Cotton Kingdom: A Traveller’s Observations on Cotton and Slavery in the American Slave States. And it included Frances “Fanny” Kemble’s Journal of A Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839.

The cruelty of chattel slavery described in Parkhurst’s books horrified Malcolm X. Writes Louis DeCaro in John Brown the Abolitionist – A Biographer’s Blog: “Malcolm went so far as to say that “Not even Elijah Muhammad could have been more eloquent than those books were in providing indisputable proof that the collective white man had acted like a devil in virtually every contact he had with the world’s collective non-white man”.”

Malcolm X Rise to Fame

Upon his release from prison, Malcolm moved to Detroit, where he worked for his brother in a furniture store and in an auto plant. Then he moved to Chicago to live with Elijah Muhammed, the leader of the Nation of Islam. He returned to Boston in 1953 to start Temple Number 11 at 35 Intervale St. in Dorchester. By the next year Elijah Muhammed appointed him minister for Temple Number Seven in New York, but he returned to Boston to build the membership of the Boston temple.

35 Intervale St. today. Photo courtesy of @ 2021 Google.

The Nation of Islam grew rapidly, in part because of Malcolm’s charisma, his tireless speaking and his message. He had little use for Martin’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance – he called it the “philosophy of the fool.” And he saw no good coming from political involvement with white people. He preached that black people must separate from the race he called “white devils,” and he defended African-Americans’ right to fight violence with violence. That resonated with black people who faced vicious white resistance to the civil rights movement in the South. They concluded whites would never grant blacks equality. It made sense to them to build all-black social and economic institutions.

Hate that Hate Produced

In 1955, Malcolm served as minister of Temple Number 12 in Philadelphia. He also founded three successful Nation of Islam temples in Hartford, Atlanta and Springfield, Mass. By 1959, a documentary about the Nation of Islam called, The Hate That Hate Produced made him a national figure.

Malcolm helped elevate Martin’s image with white people. Martin wouldn’t have anything to do with him. He refused to meet with Malcolm or respond personally to his overtures. “Fiery, demagogic oratory in the black ghettos, urging Negroes to arm themselves and prepare to engage in violence, as he has done, can reap nothing but grief,” he said.

Malcolm X guards his family home in an Ebony magazine photo.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

When Martin and Coretta Scott King permanently moved to Montgomery in the summer of 1955, a campaign had already begun to end segregation on city buses. In March, before Martin obtained his doctorate, police arrested a 15-year-old black girl. She had refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. Black activists had started to build around that case to challenge Alabama’s bus segregation laws.

Martin Luther King (left) and Rosa Parks in 1955.

Then they decided to stop riding the buses after Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on Dec. 1, 1955. Martin, not yet 30, found himself in the middle of the yearlong Montgomery bus boycott. It ended on Dec. 20, 1956, when a court ruled the state’s segregation laws violated the Constitution.

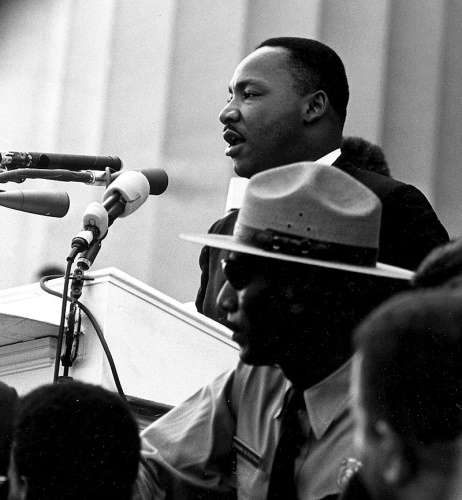

The bus boycott rocketed him to fame. In 1957 he met with President Eisenhower and formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Within the next 10 years he would be arrested in Selma and Birmingham and deliver his “I Have a Dream” Speech before 250,000 people. He would also win the Nobel Peace Prize at the age of 35 – the youngest ever to do so.

King would also lead marches in the North for better housing, better schools and better jobs. He led one such march in Boston on April 23, 1964, during one of his frequent visits to the city. The march followed a speech to the Massachusetts Legislature the day before. The audience included young lawmakers Michael Dukakis and William Bulger, reported WBUR.

March on Washington

By 1963, two events just a few months apart would indelibly stamp onto history the good-cop, bad-cop images of Martin and Malcolm. At the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Martin delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech, one of the most famous in history. Malcolm called it the “Farce on Washington.” Three months later, Malcolm would shock the world. After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, he commented the “chickens [were] coming home to roost.”

But both men were changing. Martin got more aggressive, demanding more than just integration and acceptance. More and more he aligned himself with the militant American labor movement. He once said that when he listened to Malcolm speak, even he got angry.

The March on Washington itself was organized by A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The demands of the march went beyond desegregation. They included a $2 minimum wage, a federal jobs program and the expansion of federal labor regulations to more classes of workers such as farmworkers and domestics. Many forget that Martin was assassinated in Memphis while he supported the sanitation workers’ strike.

Malcolm, too, was changing. He would soon renounce the Nation of Islam and embrace traditional Sunni Islam. In February 1965 he said, “I did many things as a [Black] Muslim that I’m sorry for now. I was a zombie then … pointed in a certain direction and told to march.”

He also recognized that the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was a stunning success. He realized he had to present a strategy to improve the lives of African-Americans. In doing so, he harkened back to work he’d done with Randolph in 1961 to fight the deterioration of York City’s black communities. Their strategy: raise workers’ wages.

MLK Meets Malcolm X

And once Malcolm left the Nation of Islam in 1964, he began to pay attention to civil rights issues and to reach out to civil rights leaders – including Martin.

On March 26, 1964, they met for the only time. The meeting lasted for about one minute, long enough to shake hands and have their picture taken. They had both come to Washington, D.C., to watch the Senate filibuster the Civil Rights Act. Eight days later Malcolm X made a speech titled “The Ballot or the Bullet.” In it, he advised African-Americans to exercise their right to vote wisely. He also announced he would form a political organization.

By then, both men correctly expected to die soon. Gunshots killed each at the age of 39. Malcolm died on Feb. 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan. Martin was then murdered on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn.

Malcolm X Meets With Coretta Scott King

Just a few weeks before he died, Malcolm X met with Coretta Scott King in Selma, Ala., while her husband served time in the Birmingham Jail. Malcolm told her he came to make Martin’s job easier. “If the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King,” he said.

To read the first part of this story, click here. We are indebted to several books for this article: The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley. Also, Malcolm X, A Life of Reinvention, by Manning Marable. Finally, Parting the Waters: America in The King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch

Images: Marsh Chapel By John Phelan – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17310479. Malcolm X with gun By Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3898865. This story was updated in 2022.

3 comments

[…] Martin Luther King called Boston his ‘second home,’ because he had lived in the South End as a graduate student at Boston University. He also courted Coretta Scott while she attended the New England Conservatory of Music. […]

[…] Martin Luther King called Boston his ‘second home,’ because he had lived in the South End as a graduate student at Boston University. He also courted Coretta Scott while she attended the New England Conservatory of Music. […]

[…] Martin Luther King called Boston his ‘second home,’ because he had lived in the South End as a graduate student at Boston University. He also courted Coretta Scott while she attended the New England Conservatory of Music. […]

Comments are closed.