On Jan. 2, 1778, the Rhode Island privateer Marlborough, with 96 Rhode Island and Massachusetts sailors on board, began its voyage to the west coast of Africa. It was one of the most extraordinary voyages of the American Revolutionary War.

Why would a privateer sail to far-away West Africa? The story starts in Providence, R.I., with John Brown, the main investor and mastermind behind the voyage. He belonged to the Brown family of Providence, among the most successful merchants in Rhode Island. In 1772, he organized and led the burning of the British revenue cutter Gaspee, an important early violent act of resistance against Great Britain. The Gaspee affair led to the Revolutionary War.

John Brown

Genesis of the Marlborough

In 1776 and 1777, Brown got rich investing in privateers. During the war, the Continental Navy was no match for the Royal Navy, the world’s strongest maritime power. America’s most effective weapon at sea by far was privateering—the operation of privately owned commerce raiders. From British ships, Americans captured gunpowder, weapons, food and other supplies they desperately needed.

Privateers were not pirates. Privateers were commissioned by the Continental Congress to attack only enemy shipping. Once a privateer captured an enemy vessel, the captain of the privateer would typically select from his ship a prize master and a small prize crew. They would sail the captured vessel to a safe U.S. port so an admiralty court could adjudicate the prize. The admiralty court would conduct a trial by jury to determine whether the privateer had lawfully taken the prize from an enemy combatant. If it was, it would be sold at public auction. The net proceeds would be divided. Typically, 50 percent would go to the privateer’s owners. The rest would go to the privateer’s officers and crew pursuant to a formula agreed to before the voyage.

The 12-gun privateer brig Independence, on the left and commanded by Thomas Truxton, captures a larger and better armed British merchant ship sailing from the Caribbean, in 1777. Watercolor by Irwin Bevan (1852-1940). (Naval History and Heritage Command).

In the early years of the war, American privateers easily seized hundreds of poorly-defended merchant ships sailing between Britain and both the Caribbean and Canada. Brown grew rich. But the days of easy conquests eventually ended. Powerful Royal Navy warships began protecting commercial vessels in convoys and seizing privateers. Most crews of captured privateers went to British prisons in New York or back in Britain. Many of the prisoners died of malnutrition and disease.

Off to Africa

Brown decided in the second half of 1777 that, with his new wartime profits, he could afford to construct a large privateer that carried at least 20 cannon. Such a privateer could avoid capture by a British sloop-of-war and defeat armed merchantmen. But it could still be captured by a 32-gun Royal Navy frigate, many of which were hunting for privateers in the British Caribbean and on the Canadian coast. What to do? Brown had the brilliant idea of sending his new privateer to the coast of West Africa.

Brown figured, correctly, that the Royal Navy was overstretched. It had few ships remaining to patrol the far-away African coast and British interests there.

The Atlantic Slave Trade

At the time, one of the worst tragedies in world history continued unabated: the Atlantic slave trade. European and American merchants sent ships across the ocean to purchase African captives. They then carried them to the Caribbean islands, Brazil and the North American mainland. There the Africans were forced into a lifetime of unpaid work and permanent bondage. The captives were taken away from their families forever, and thousands of them died during the voyage across the Atlantic, called the Middle Passage. It was a horrible, abominable trade, and it is mind boggling to believe it ever existed, especially by today’s moral standards.

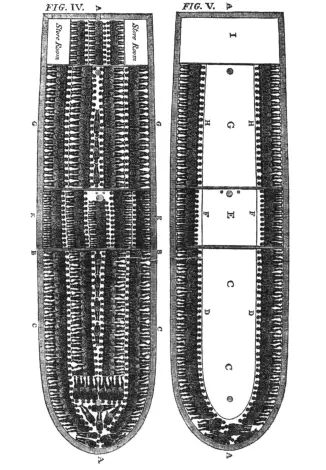

Diagram of a slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade. It shows how kidnapped Africans were jammed into the ship’s hold.

In the first three-quarters of the 18th century, Great Britain led the world in slave trading. The year 1775 marked the zenith of Britain’s slave trade, led by merchants from Liverpool, Bristol and London.

A British slaving voyage typically had three legs, thus giving rise to the name “triangular trade.” Starting from Britain, the slave ship sailed to the African coast carrying goods mainly manufactured in Britain, such as muskets, gunpowder and textiles, used to trade for African captives. Then the ship carried the captives across the Atlantic to a Caribbean possession of Britain—such as Jamaica, Barbados or Antigua. There the surviving captives were ultimately sold to local plantation owners. Next, the ship’s captain purchased sugar—and related products, rum and molasses—to bring back to Britain to sell to British wholesalers.

Enslaved workers planting sugar cane in Antigua.

Sugar

Sugar was the key. Europe craved sugar, and the English in particular loved sugar in their cookies, cakes, tea and coffee. The value of sugar imports, and molasses and rum, from the British Caribbean by far outstripped the value of imports of tobacco from the colonies of Virginia and Maryland, and rice from South Carolina.

Slave labor was indispensable to the production of sugar. Plantation owners in the Caribbean islands used gangs of enslaved workers working in brutal conditions to cultivate, harvest, and process sugar cane into sugar.

The continuation of slave labor depended on the African slave trade. This was because sugar plantation owners needed to replenish their slave stock each year by purchasing new captives.

Enslaved people in the British Caribbean, due to poor food, primitive living conditions and overwork, left them vulnerable to deadly diseases. The mortality rate was shocking, much worse than for the enslaved in North America. As a result, British Caribbean planters had to import massive numbers of African captives just to maintain their enslaved populations.

What would become the United States and later became the United States overall played a comparatively small role in the African slave trade, outfitting only about 2.4 percent of all slaving voyages. Rhode Island dominated the slave trade among the thirteen mainland colonies. More than half of the North American slave trading voyages in colonial times emanated from Rhode Island (primarily Newport), with the rest coming mostly from New York City, Boston and other coastal New England ports.

John Brown

What led John Brown to his idea to send a privateer to distant Africa was his familiarity with the African slave trade. First, coming from Rhode Island, he could speak with returning slave ship captains to discover that few or no British warships patrolled the West African coast.

Second, Brown was himself an experienced slave trade investor. He had personally invested in two African slaving ventures, one in 1763 and another in 1769.

Brown was also aware, from reading newspapers, that beginning in early 1777, American privateers started to capture British slave ships. In most cases, American privateers captured British slave ships with hundreds of African captives on board just as they were about to reach their destinations in the British Caribbean. The American privateers typically sailed the seized vessel to a French Caribbean island and sold the human cargo there to French plantation owners.

Brown was not motivated to attack Britain in Africa from humanitarian impulses to aid Africans. But he did want to harm British economic interests and, at the same time, earn profits doing so.

A Privateer in Africa

A privateer sent to Africa could attack and plunder slave trading posts established by British slave traders. Such a post typically contained warehouses full of British manufactured goods intended for the local slave trade. The privateersmen could carry off this booty and load the goods into the holds of their privateer. In addition, African captives kept in pens at the slave trading posts, intended to be sold to passing British slave ships, could also be seized. Moreover, British slave ships with its human cargo on board could be captured.

Kidnapped Africans bound for slavery

If Brown was really fortunate, he figured, his privateer could capture a large British slave ship filled with African captives, ready to sail for the Caribbean islands. A prize crew from Brown’s privateer would be ordered to sail the slave ship in the Middle Passage and try to arrive at a safe port, in one of the French-controlled Caribbean islands or in American-held Charleston, S.C., or Savannah, Ga. There the surviving enslaved Africans on board could be sold. Then Brown and his investors could really cash in.

Brown completed construction in Providence in late 1777 of a new 20-gun, three-masted brig. He named it the Marlborough. After breaking through a blockade of British warships (a close call), the privateer sailed to Martha’s Vineyard. There, 24 more crew members enlisted for the voyage. It then departed for Africa on Jan. 2, 1778.

The Story of the Marlborough

My recent book, Dark Voyage, An American Privateer’s War on Britain’s African Slave Trade (Westholme, 2022), tells the tale of the remarkable voyage of the Rhode Island privateer Marlborough to West Africa.

Most of the book is about the Marlborough’s voyage. In short form, here are some of the notable events from the voyage.

The New England privateersmen sacked and took out of operation one of the top British slave trading posts in Africa. They also captured several armed British slave ships and sailed them as prize ships back to North America.

One British slave ship, when seized, had more than 300 African captives on board. It was about ready to sail for the British Caribbean, just as John Brown hoped. The Marlborough returned to New Bedford, Mass., with 26 African captives on board.

A number of African leaders cooperated with the New Englanders, including King Tom. He had served as an intermediary for European and American slave ship captains for decades. Several British slave ship captains greedily agreed to cooperate with the New Englanders by giving them valuable intelligence. They did it even though that meant committing treason against their own country.

Impact of the Marlborough

The Marlborough damaged the British slave trade more than any other American privateer. In my book, I argue that the actions of the officers and sailors of the Marlborough, as well as those of other American privateersmen who intercepted British slave ships at sea, had a stunning unintended consequence. The British slave trade by 1778 had not only been disrupted, it had virtually collapsed. American privateersmen interfered with the conduct of the British slave trade to such an extent that British slave merchants substantially reduced their investments in African slave voyages. By 1778 the reduction was more than 70 percent. As a result, during the early years of the Revolutionary War, the number of enslaved Africans forcibly shipped across the Atlantic Ocean declined dramatically. It fell perhaps by as much as 60,000 and probably more.

On the other hand, the men of the Marlborough and other American privateersmen, when they did capture British slave ships, became crass slave traders, hoping to sell their captives for as high a price as possible. The privateersmen can thus be viewed as heroes or villains—or both.

The American Revolution, with its rhetoric emphasizing liberty and freedom, ultimately led virtually all states to abolish the African slave trade. However, due to a compromise with South Carolina in negotiating the U.S. Constitution, and some illegal slave trading, total abolition didn’t happen until January 1, 1808.

Christian McBurney, the author of this story about the Marlborough and the related book, has authored six books on the American Revolution and co-authored two on Rhode Island in World War II. He is also the editor and publisher of a leading Rhode Island history blog at smallstatebighistory.com.