In 1959 the CIA named Richard Bissell its deputy director for plans. The agency had made an unusual selection.

Richard Bissell

Bissell replaced Frank Wisner, his complete opposite. Wisner came directly from central casting as the shady OSS spy from World War II. The agency hired Bissell to reflect the new CIA.

Wisner’s FBI file tells scurrilous tales of his wild life during and after World War II. He lived in Romania with a beautiful Russian spy. That complicated his relations with the Romanian industrialists in Romania rebuilding their country. He was also accused of skimming relief supplies destined for the Red Cross and diverting them elsewhere. A rumor pursued by Sen. Joseph McCarthy suggested Wisner, a one-time Wall Street lawyer, profited off the sale of ships after the war — perhaps improperly.

By 1958 Wisner’s cowboy career as a spy had careened out of control. Diagnosed as bipolar, Wisner was hospitalized. When his return to the agency became impossible, he went into exiled. Wisner would eventually commit suicide.

Richard Bissell, Blueblood

Searching for a replacement as deputy director of plans, CIA director Allen Dulles chose a man who could not be less like Wisner: Richard Bissell. Bissell embodied the very definition of a New England blueblood.

Richard Bissell’s ancestor, Samuel Bissell, had belonged to George Washington’s spy corps. Richard’s father, a successful insurance executive in Hartford, bought Mark Twain’s mansion. Richard Bissell, born Sept. 18, 1909, grew up in the house. He spent summers in exclusive Dark Harbor, Maine.

The Mark Twain House in Hartford

Educated at Groton and Yale, he then taught economics as a professor at Yale. He spent a year as an economist at the Commerce Department in Washington. But that turned into an assignment that lasted throughout World War II. Then after the war, Bissell emerged as a rising star. He oversaw elements of the Marshall Plan, which directed funds for rebuilding Europe following the war.

Bissell was also independent and self-confident. He refused membership in Yale’s Skull and Bones secret society. His circle of friends included intellectuals and spies alike. McGeorge Bundy, President Kennedy’s national security advisor, had studied under Bissell at Yale.

The year 1951 found Bissell working at a Washington think tank and pondering his career options. He belonged to the Georgetown set of young professionals blossoming in Washington at the time. The lure of spying proved too strong a pull for him.

New Tricks

At the urging of Wisner and Dulles, Richard Bissell joined the CIA. He then moved the agency away from the old tools of the spy trade — informers, tipsters and tricksters. Instead, he championed the electronic collection of data.

While rudimentary compared to today’s government electronic eavesdropping apparatus, Bissell promoted the development of the U-2 spy plane program and satellite data-gathering capabilities.

The U-2

Older hands at the CIA raised eyebrows, but Dulles tapped Bissell as his new deputy of plans in 1959 following Wisner’s flameout. Data-gathering seemed a far cry from the spy-vs-spy trickery that he now oversaw.

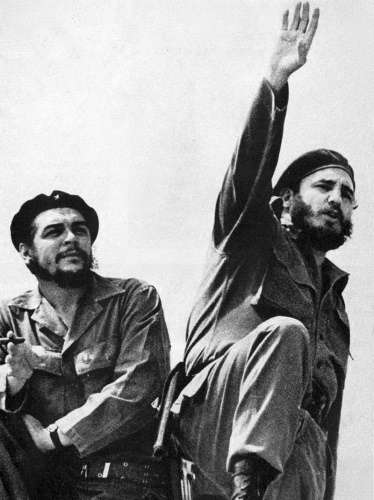

Communism was now enemy number one in Washington. President Eisenhower intended to curb communism in Central and South America. Fidel Castro had swept to power in a populist revolution in Cuba. Initially, he bamboozled American diplomats about his intentions.

When Castro eventually revealed himself as a Communist, the Eisenhower administration determined he needed to go. The CIA began developing schemes within the country to destabilize Castro. But they got nowhere with fires, minor protest efforts and subversive radio broadcasts.

The Legend of Richard Bissell

The United States needed a bolder plan. Bissell was the man for the job. Bissell’s CIA biography notes, ”He became a CIA legend because he dared to take risks during one of the nation’s darkest periods, the Cold War.” The bio understated the facts badly by calling the Bay of Pigs invasion “risky.”

Eisenhower, in one of his last meetings with the CIA managers, told them they must act boldly to stop the spread of communism in the west. When Kennedy then won the presidential election, nothing changed in the country’s approach to Cuba.

At that time Bissell wrote to a friend. “My guess is that Washington will be a more lively and interesting place in which to live and work. Even so . . . I am not sure how much longer I want to stay in this business.”

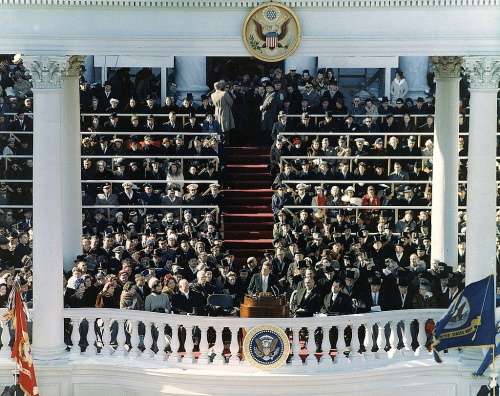

Kennedy Arrives in Washington

By the time of Kennedy’s inauguration, the CIA had sketched out the outlines of the Bay of Pigs invasion. The CIA actively trained a 1,400-man fighting force of Cuban exiles in Guatemala to carry out the raid. They planned to launch from Nicaragua and topple Castro.

JFK inauguration

The use of guerrilla fighters wasn’t so far-fetched. A CIA-backed group of guerillas had ousted Guatemala’s leader in 1954. Students of that coup say the CIA drew the wrong lessons from it. Far from being a masterful operation, the fighters in the Guatemala coup had incredible luck. Instead of inspiring a similar raid, it should have warned what not to do.

Early on, Kennedy asked whether the Joint Chiefs of Staff had vetted the Bay of Pigs plan. When he learned it had not, Kennedy applied the brakes and then asked for a review.

Within the CIA, people viewed the invasion plan with a mix of skepticism and awe. They saw it as bold, no doubt. Sending a small army to invade Cuba was audacious. It was a far cry from smaller agency efforts such as acts of sabotage and disinformation campaigns. The plan struck some as flying in the face of some of the agency’s guiding principles. A typical CIA operation had the parameters of small risk/big reward. The Bay of Pigs appeared to represent an enormous risk.

The Bay of Pigs Plan

The plan as presented to Kennedy was relatively simple. A squadron of US bombers, painted and disguised as Cuban aircraft, would bomb Cuba’s airfields. A landing force of 1,400 men would arrive at the Cuban city of Trinidad, where Castro was unpopular.

With air cover for the landing troops, the men would create a stronghold and begin moving inland, soliciting support from anti-Castro locals to strengthen the invading force as it went. Supplies would arrive by ship and the force would, hopefully, oust Castro.

Che Guevera and Fidel Castro

If things went badly, the fighting force would flee to the Escambray Mountains. There, an anti-Castro resistance movement had its home. They would regroup and take part in a smaller resistance movement that might, over time, hobble Castro.

The Joint Chiefs’ review of the plan was quite critical. The logistical planning was inadequate. There was no bridge-building equipment called for, no lighting for night operations, inadequate men and equipment to handle heavy loads and very few men trained in amphibious assault.

Without a massive show of support from the residents of Trinidad, the invasion would sputter. Even moderate resistance would cripple the landing. And, the review noted, the attack, given its size, would not likely surprise anyone.

Plan B

Weeks before the assault, planned for April of 1961, a rework was called for. The attack could not be seen as an American enterprise. It needed a lower profile, so journalists would only slowly witness it. That meant the elimination of Trinidad as a target.

The CIA scrambled to find a new target. They chose the remote and lightly populated Bay of Pigs. The bay was unprotected and could be attacked, but the change undermined a number of elements of the original plan.

- It was unlikely to generate a mass uprising, as the area was remote and not anti-Castro.

- The beach was not easy to operate on, and it would be difficult for soldiers to move inland.

- It would be harder to operate at night in the remote setting, and.

- If the invasion failed, there was no chance to retreat into the Escambray Mountains to join up with fledgling anti-Castro resistance.

Now they had no Plan B.

Finally, just hours before the attack, Kennedy gave one last instruction to Bissell. He wanted the invasion to be even quieter. The details he left to Bissell.

Bissell scaled back the air support for the attack. A fleet of 16 aging B-26 bombers had been acquired and doctored to look like Cuban aircraft. The older planes could plausibly have been stolen from Cuba’s aging air force fleet. Bissell ordered that eight planes should hold back. There would now be about 40 airstrikes to support the men on the ground.

He owned it.

Invasion Day Disaster

The disaster at the Bay of Pigs has been well cataloged. In brief, the first wave of bombing attacks damaged, but did not destroy, the Cuban Air Force.

Journalists got sight of the planes involved and immediately identified them as American, not Cuban. The press had already reported stories about the CIA training a Cuban invasion force. At the United Nations, U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson testified that the air strikes had nothing to do with the United States.

With soldiers readying to land on the beaches, the invasion plan got one final haircut. President Kennedy cancelled additional air support for the invasion.

Douglas A-4 Skyhawks flying sorties over combat areas during the invasion

Then on April 17, 1961, 1,400 paramilitaries assembled and launched from Guatemala and Nicaragua. That night, they landed on the beach at Playa Giron in the Bay of Pigs.

At first, things went well. The invasion force overwhelmed a local militia. But the Cuban Army counter-attacked. Castro later took control of Cuba’s defense.

With no air support, the Cuban Air Force battered the invading troops. Then Cuban planes sunk two supply ships carrying ammunition, weapons and food. Others dared not approach the island.

One final use of air power was authorized to give ships cover to offload supplies. But the timing was miscommunicated and the resupply never occurred.

Counterattack near Playa Giron

The end result was inevitable. Three days after landing, the invaders surrendered.

On the American side, 122 men died; on the Cuban side, 176 lost their lives.

The Aftermath

From Bissell’s perspective, the final nail in the coffin for the invasion plan came when President Kennedy rolled back the air support.

Bissell and his fellow deputy director Charles Cabell had gone to the White House as Kennedy weighed the decision to reduce the air support. Bissell had the chance to try to persuade the president personally, but he declined. He left it to Secretary of State Dean Rusk to convey his opinions.

“Today I view this decision . . . as a major mistake,” he later wrote. “For the record, we should have spoken to the president and made as strong a case a possible on behalf of the operation and the welfare of the brigade.”

Back at CIA headquarters, outrage greeted the decision to curtail the air war.

“This is the goddamnest thing I have ever heard of,” one CIA planner shouted. Bissell wrote that he let Cabell deliver the message, “probably out of cowardice.” And so Cabell bore the brunt of everyone’s anger.

Bissell’s career with the CIA did not survive the fiasco. The agency offered him the chance to return to work improving the agency’s data collection and electronic spying. But he declined and then resigned in 1962, eventually returning to Connecticut.

Kennedy would award Bissell the National Security Medal for his work with the CIA. Bissell would then end his career in private industry.

Bissell’s Thoughts

For the rest of his life, Richard Bissell was linked to the Bay of Pigs, and he did not avoid the topic. He addressed it in detail in his memoir, Reflections of a Cold Warrior: From Yalta to the Bay of Pigs. Bissell never denied responsibility for the disaster, though he did feel unfairly treated in the operation’s reviews.

The CIA inspector general, Bissell felt, had gone out of his way to smear him. He did it, possibly, to clear the way for Bissell’s rivals within the agency. Richard Helms reported to Bissell, and Bissell had passed over him as deputy director.

Helms had given the Bay of Pigs operation a wide berth and then took over after Bissell resigned. Eventually he rose to CIA director.

Bissell also bridled at the inspector general’s charges that the Bay of Pigs planning involved no first-rate CIA staff.

Some scholars maintain the Bay of Pigs insurgency had no chance because of limited anti-Castro sentiment in Cuba. The larger Cuban military, they contend, would have put down the invasion regardless.

The president and Mrs. Kennedy greet a brigade of Cubans from the Bay of Pigs disaster

Others have suggested the anti-Castro Cubans hoped to draw the U.S. military into the fight. If they did, Bissell said, they never got that impression from him or his men. The United States would never come to the rescue, he contended. The CIA made that clear from the start to all parties.

Richard Bissell himself maintained that the cancellation of air support doomed the mission. While the invasion might not have toppled Castro, Bissell argued, the thrashing of the invasion force wouldn’t have happened with air support.

Shoulda, Woulda, Coulda

So why didn’t he object more strenuously as the air support got whittled away from the plan? He wrote:

We should have told (the president) clearly ahead of time that if he wanted to exclude that part of the plan the whole plan had to be reconsidered.

“I think I retained too much confidence in the whole operation up to the end, more than was rational,” he wrote. “But that’s the way it was.”

“So emotionally involved was I that I may have let my desire to proceed override my good judgment on several matters.”

Richard Bissell died Feb. 7, 1994.

This story last updated in 2023.

Images: Attack near Playa Giron By Rumlin, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=49446605. JFK greeting 2506 brigade By Cecil Stoughton – https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKWHP/1962/Month%2012/Day%2029/JFKWHP-1962-12-29-A, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=87338494. Mark Twain House By Kenneth C. Zirkel – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21778275. Map of Cuba By Cacahuate – Own work based on the map of Cuba provinces by Joshbaumgartner, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22746281.

2 comments

[…] meanwhile, had been famously shot down flying an American CIA U-2 spy plane over Russia in May of […]

This story is the cia in a nutshell. Stupid and insane.

Comments are closed.