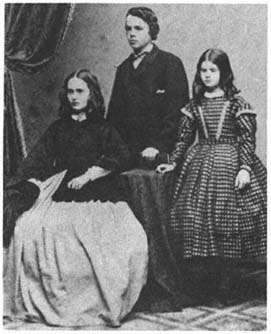

Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, the youngest daughter of Nathaniel Hawthorne, is a candidate for something the Puritans abhorred: Catholic sainthood.

She was born on May 20, 1851 in Lenox, Mass., the third child of Sophia Peabody and Nathaniel Hawthorne. He was then basking in the success of his first best seller, The Scarlet Letter, which chronicled the Puritan mind. Both Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne came from old Puritan stock.

Rose would spend the first 50 years of her life as one would expect of the well-to-do daughter of a literary giant: marriage, travel to Europe, mingling with the literati and East Coast society.

But after 50 years she took on a new identity. She took her vows as a nun after her closest family members died, her marriage disintegrated and her only brother feuded with her.

Early Life

During her first nine years, Rose Hawthorne lived in Massachusetts, Paris, Italy and England, where her father served as U.S. consul general to the British government. His friend President Franklin Pierce appointed him to the post.

Her father died in 1864, the day before her 13th birthday, while the family lived in Concord, Mass.

After his death, Sophia Hawthorne brought her children to Germany, then England, to live.

Marriage — And Then

Just after her mother died, 20-year-old Rose married George Parsons Lathrop in London. He was a poet, novelist and editor, but not to her brother Julian’s liking. He thought George immature and Rose acted too hastily after her mother’s death.

But at first they had a happy marriage. They moved in literary circles; he as editor of the Atlantic Monthly and the Boston Courier, she as a poet, short story writer and daughter of the great Nathaniel Hawthorne.

They had one son, Francis. They then returned to the United States and bought The Wayside, where she had lived twice before as a child among the Alcotts, the Emersons and the Thoreaus. When 5-year-old Francis died of diphtheria, the couple moved out.

George began to drink heavily and Rose spent more time on her own. Her family began to fall away. Her sister, Una, died in 1877, and she feuded sporadically with her brother.

George Parsons Lathrop

In 1881, she befriended Emma Lazarus, who wrote the poem at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Lazarus’ death from cancer at age 38 affected Rose profoundly – as did her involvement with the Catholic Church.

George and Rose Hawthorne Lathrop had moved to New London, Conn., in 1887. In 1891 they both took the then-radical step of converting to Catholicism. It didn’t save the marriage.

Rose finally walked away from George in 1895. He died three years later of cirrhosis of the liver.

A New Chapter

Rose Hawthorne Lathrop was in her mid-40s and alone. But Lazarus had made her aware of the plight of people who were far worse off than she – impoverished cancer victims.

A Catholic priest, Father Alfred Young, told her the story of a poor seamstress diagnosed with cancer. She could no longer work or rely on her family, so she ended up in a poor house at Blackwell’s Island. There the poor woman had no medical treatment or nursing care.

“A fire was then lighted in my heart, where it still burns,” Rose later wrote. “I set my whole being to endeavor to bring consolation to the cancerous poor.”

People then believed cancer a highly contagious disease. But they had not place to go. Once diagnosed, they were banished to die alone.

Nursing the Sick

Rose, then 45, moved to New York and took a three-month nursing course at New York Cancer Hospital. In the fall of 1896, she moved into a cold-water flat in one of New York’s worst slums, the Lower East Side.

At first she visited poor cancer victims in their homes. Then she invited them into her own apartment, where she washed their sores and changed their bedclothes. To help raise money, she wrote Memories of Hawthorne.

A few years later she moved into a house on the Lower East Side with an assistant, Alice Huber. Benefactors had contributed the down payment to the house, known as St. Rose’s Free Home for Incurable Cancer. There they cared for 15 poor cancerous women at a time.

Rose Hawthorne, Nun

On Dec. 8, 1900, Rose Hawthorne was invested in the Dominican habit and took her first vows, along with the name Mother Mary Alphonsa. She founded a religious order called the Servants of Relief for Incurable Cancer. They only cared for the most destitute and refused any kind of compensation.

Her mission, she said, was:

To take the neediest class we know — both in poverty and suffering — and put them in such a condition that if our Lord knocked at the door I should not be ashamed to show what I have done. This is a great hope.

For the next 26 years she would care for destitute cancer patients believing everyone has a right to die with dignity. She established a second nursing home, Rosary Hill, in a Westchester County hamlet, just north of New York City. The hamlet renamed itself Hawthorne, and she lived there for the rest of her life.

The Rosary Hill nursing home founded by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop.

She died in her sleep on July 9, 1926, her parents’ 84th wedding anniversary. Her order is now known as the Dominican Order of Hawthorne.

In 2003, Rose Hawthorne Lathrop was nominated for sainthood. The road to canonization is long and uncertain. The Puritans, though, thought all Christian believers are saints.

This story about Rose Hawthorne was updated in 2024. Image of Rosary Hill Home By Midnightdreary – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31762281.

9 comments

Wow, thank you, I learn a lot from your posts.

I learned alot. I did not know any of this

I went to Rose Hawthorne School in Concord, and never knew any of this about her. I love that she was influenced by Emma Lazarus.

She shows at any age, you can change your life path.

Never knew this…

[…] have been smart and charismatic, for she was able to enlist Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thomas Carlyle and Nathaniel Hawthorne in her tragicomic campaign to debunk Shakespeare’s authorship. She crossed the Atlantic to […]

[…] himself never declared a particular religious affiliation, but he did enjoy stirring the pot with his stories, which were layered and designed to be […]

[…] incurable cancers. She died in 1926 and was buried on the grounds of her order’s Motherhouse. In 2003 Rose was nominated for sainthood. Julian died in San Francisco in […]

[…] New England Historical Society […]

Comments are closed.