Quaker persecution began in Massachusetts in July 1656 as soon as the first two Quakers sailed into Boston Harbor. Mary Fisher and Ann Austin arrived on the Swallow, a ship from Barbados, with a trunk full of Quaker writings.

Puritan magistrates had them strip searched in public for signs of witchcraft, jailed them, deprived them of food, confiscated their belongings and put them back on the Swallow when it sailed away eight weeks later.

To the Puritans’ horror, eight more Quakers arrived in Boston shortly after Fisher and Austin. The General Court passed an edict that imposed a heavy fine on any ship’s captain who brought Quakers into Boston. The eight Quakers were beaten and jailed, and the captain who brought them had to take them back to England.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony then banned Quakers — in 1656, 1657, 1658, 1659 and 1660 — and sent letters to the other New England colonies suggesting they do the same. Connecticut followed suit in 1656; Rhode Island refused.

The colonies got away with Quaker persecution until the restoration of the English monarchy. Then, Charles II tried to stop the Puritans from persecuting Quakers – or other heretics such as Catholics or Lutherans. And at that point Quaker persecution was more than an exercise in religious intolerance; it was about maintaining political independence from the Crown.

New England Way

Samuel Sewall

The Puritans had endured much to establish the New England Way, a system based on the power and independence of the congregation. The church was sovereign; the state subordinate to the church.

To create their moral community – their ‘city on a hill’ – the Puritans had left their homes, sailed across the Atlantic and confronted the terrors of the wilderness.

The Quakers who continued to arrive in the mid-1600s were anything but gentle peaceniks. They deliberately disrupted the Puritan community. When the self-righteous Quakers came to town they yelled in the streets, banged pots and pans, shouted during church services and stripped off their clothes.

Samuel Sewall in his diary recorded one such disturbance:

In Sermon time there came in a female Quaker, in a Canvas Frock, her face as black as ink, led by two other Quakers, and two others followed. It occasioned the greatest and most amazing uproar that I ever saw.

Burning Quakers

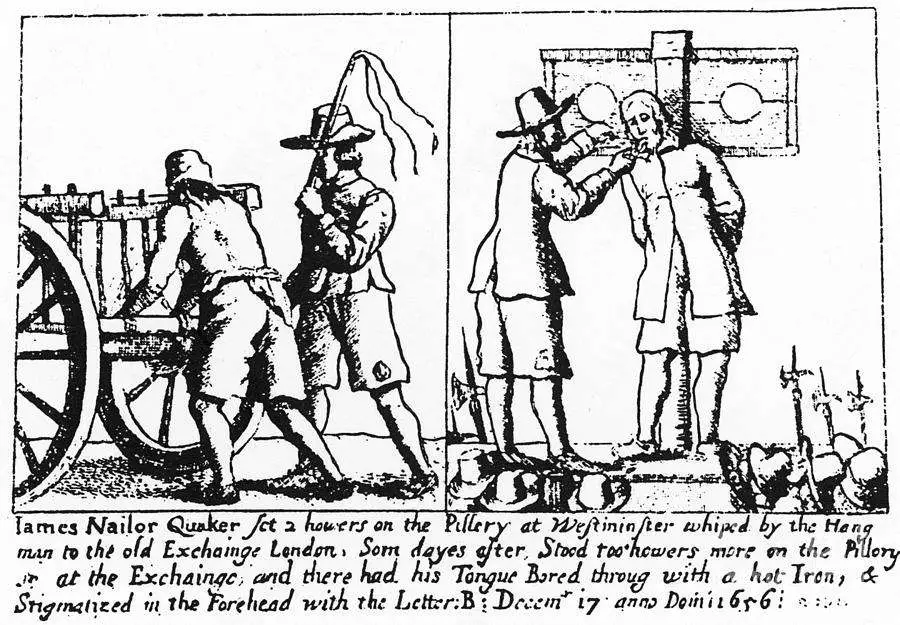

The Puritans responded by cruelly punishing Quakers. They whipped them, branded them, cut off their ears, bored holes through their tongues and hanged them.

Rev. John Norton, a leading Boston minister, cried, “I would carry fire in one hand and faggots in the other, to burn all the Quakers in the world.”

That didn’t stop the Quakers.

The punishment for a Quaker to set foot in Massachusetts in 1660 was death by hanging. Quaker Mary Dyer chose to die to expose the cruelty of the Puritan theocracy

The Quakers even exasperated Roger Williams, that paragon of tolerance. Though the other colonies threatened Providence Plantation with a trade embargo because it tolerated Quakers, the Quakers treated Williams disrespectfully. Wrote one historian,

Williams was taken aback by his Quaker opponents’ boisterous behavior and abandonment of common courtesy during the debates. He vehemently objected to their habit of interrupting his arguments, shouting him down, attempting to humiliate him personally with name-calling and ridicule, misrepresenting his convictions, and displaying a noted lack of truthfulness in their own arguments.

Stopping the Quaker Persecution

In 1660, the English monarchy was restored. Quakers went for help to King Charles II, a Catholic sympathizer. He had no liking for the Puritans, who had executed his father and taken refuge in New England.

A Quaker named Burroughs was said to have told the monarch, “There is a vein of blood opened in your dominions which, if not stopped, will overcome all.

”I will stop that vein,” Charles supposedly replied.

Then in 1662, the king sent a letter to Massachusetts ordering him to stop the Quaker persecution.

According to the king’s missive, the colony should send Quakers accused of crimes – unharmed – to England for trial. A Quaker named Shattuck, who the Puritans had sent back to England, then brought the letter to Gov. John Endicott. Word spread that “Shattuck and the devil had come.”

Endicott said he would obey the king’s command. But only gradually did Massachusetts Puritans lessen their persecution of Quakers.

This story about Quaker persecution was updated in 2022.

19 comments

[…] Her ancestor Daniel Gould came from England and settled in Newport in 1637. He became a member of the Society of Friends and married the daughter of John Coggeshall, the first president of the Aquidneck Colony who was also a Quaker. […]

[…] where she attended some of the more exotic religious services of the day among the Baptists and Quakers. Lady Moody became an Anabaptist — a school of thought that held that people should not be […]

[…] Mass. Her father was Major League Baseball player Sidney Farrar, an infielder for the Philadelphia Quakers and Philadelphia […]

[…] Massachusetts would continue persecuting Quakers, even executing some such as Mary Dyer, until 1660 when the monarchy returned to England and the king ordered Massachusetts to stop. […]

[…] Massachusetts would continue persecuting Quakers, even executing some such as Mary Dyer, until 1660 when the monarchy returned to England and the king ordered Massachusetts to stop. […]

[…] One of the Johnson properties was a residence, the other a Quaker meetinghouse. […]

[…] Presbyterians and Baptists, even a Quaker ran the religious revival camps. It was the Methodists, though, who brought the camp meeting east […]

[…] Crowninshields, Forbes, Hunnewells, Lodges, Lowells, Parkmans, Perkins, Russells, Saltonstalls, Shattucks, Shaws and […]

[…] Quakers Nathan and Mary Johnson harbored Frederick Douglass in 1838 at their home in New Bedford, Mass. The couple were free blacks who married in 1819 and became part of New Bedford’s robust African-American community. […]

[…] who was astute enough to get out of whaling before the industry collapsed. Edward Robinson, a Quaker, also taught her the value of plain […]

[…] the summer of 1682, a stone-throwing devil persecuted a Quaker tavern owner named George Walton in what is now New Castle, […]

[…] woman held forth for so long that Knight feared she was a Quaker, then a minority much reviled by the Massachusetts […]

[…] from a long illness. Then, to support herself, she got a job as a mother’s helper to a successful Quaker merchant, William Augustus Brown. Brown moved his family to Brooklyn, N.Y., and Eliza, Elizabeth […]

[…] and Lightfoot’s stock in trade was disguise, posing as Quakers, beggars and physicians. They also altered their ages and features. But the hunt for them was so […]

[…] Like many Quakers of the era, Thomas Maule spoke out against the Puritans for their cruelty and intolerance. He received 10 stripes of the whip for saying Salem John Higginson, ‘preached lies and instructing in the doctrine of devils.’ […]

[…] had 9 brothers and sisters, and all the children were given a quality education. They were Quakers, and intellectual equality was a tenet of the Quaker […]

[…] Hussey Macy was born in Nantucket on Aug. 30, 1822, the fourth of six children in a seafaring Quaker family. At 15 he shipped out aboard the whale ship Emily Morgan and spent four years at sea. He […]

[…] battles set up the British for their final defeat at Yorktown. Nathanael Greene, the limping Quaker, returned to a hero’s welcome in Rhode Island. He didn’t stay long, however. The South Carolina […]

[…] least one of his victims, Mary Dyer, has gone down in history as a courageous woman whose stand against religious intolerance cost her […]

Comments are closed.