In the Connecticut River Valley town of Amherst, Mass., a footpath hidden from the street connected two regal mansions overlooking Main Street. Emily Dickinson often trod that path to the house next door. It was, she said, “wide enough for two who love.”

The Homestead

Emily lived in The Homestead, the Federal style mansion on the right. Her brother and sister-in-law lived in the Italianate mansion, The Evergreens, on the left.

For fifteen years, Emily and Susan Dickinson trod the path back and forth, exchanging poems and letters and drawings, along with flowers and treats. So did children, and servants, and friends, and Emily’s sister Lavinia and Susan’s husband Austin. The two households lived in each other’s pockets.

The Evergreens

Emily Dickinson House

Far from being a gloomy mansion sheltering a recluse, The Homestead was the setting for the Dickinsons’ warm, intimate family life. Stablehands worked in the barn between the two homes. Gardeners tended the vegetable garden and orchards. Cooks and maids ran the household, and nursemaids took care of Austin and Susan’s three children.

At night the houses stilled, but well before dawn a light would appear in the upstairs window of The Homestead. Emily had lit the lamp in her bedroom. She sat at her tiny cherrywood table and penned letters, poems, letter-poems and drawings. As a sometimes sickly girl, she had made a deal with her formidable father. He allowed her to stay in her room and write until noon. Then she’d have to help with the household chores—baking, gardening and the hated sewing.

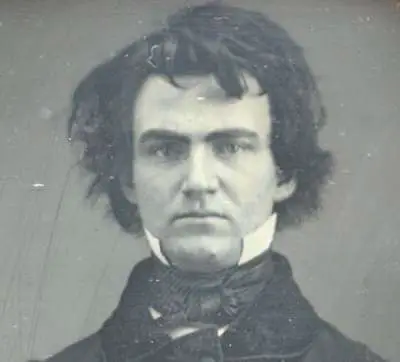

Retouched daguerrotype of Emily Dickinson

Over time, Emily lost interest in small talk, church service and shallow social gatherings. She wanted to wrestle with questions about nature, life and death, and to write poetry. Her extended family, her tight circle of correspondents and her friends were enough.

Once, Emily invited her niece to her bedroom. She closed the door behind them, locked it with an imaginary key and said, “This is freedom.”

Susan Dickinson

Emily sent several hundred of her poems to Susan, who understood their power. Emily considered Sue her most perceptive critic.

Sue was an accomplished woman in her own right. She invited the leading intellectuals of the age to soirees at The Evergreens. Over exquisite meals she exchanged witticisms with her guests, well-known figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Wendell Phillips and Frederick Law Olmsted. Sam Bowles, editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican, was a favorite of both Susan and Emily. A few years earlier, he had tried to persuade Amherst College to honor Sue with an honorary degree for her intellect and social adroitness.

Susan Dickinson

Susan had made the The Evergreens a showplace. She filled the rooms with stylish carved furniture and covered the walls with oil paintings. On cold nights a fire crackled in a green marble fireplace. In warm months bunches of her prize-winning flowers brightened the rooms.

Interloper at The Homestead

When a vivacious young faculty wife and her astronomer husband came to town, Sue invited them to her soirees. Mabel Loomis Todd was ambitious, but neither she nor her husband had any money.

The interloper: Mabel Loomis Todd

Mabel called The Evergreens “a pleasure haven,” quite the contrast to the boardinghouse she and her husband lived in. But then she began a 13-year-passionate affair with Austin Dickinson. Sue found out, and Mabel was no longer welcome at the The Evergreens soirees.

Mabel and Austin would tryst at The Homestead. Austin would trod the path for his assignations behind closed doors in the library or the dining room. Emily and Lavinia had to put up with it — Austin handled their finances. He gave Mabel a piece of Dickinson land across Main Street and helped pay for the 13-room house she built on it.

Before Mabel started sleeping with her husband, Sue shared some of Emily’s poems with her and told her about her rare genius. Mabel ardently wished to meet Emily. Emily would have none of it. Every time Mabel sent her a gift or a note, Emily sent her a thank you note laced with sarcasm.

The first time Mabel laid eyes on Emily was in her coffin.

The Story of Emily Dickinson

Emily had wished Sue would “tell her story.” Sue had hundreds of Emily’s poems in her possession, and wanted to bring them to the public’s attention.

But Mabel had insinuated herself into Lavinia’s good graces. She managed to get hold of more than 600 of Emily’s poems. With a Boston man of letters, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, she edited three volumes of Emily’s poems and a collection of her letters. The first edition of Emily’s poems sold out in one day. Mabel rode the wave of interest in the poet by giving lectures on “her friend” Emily Dickinson.

However, Mabel had a problem: How to square the fact that she’d never met Emily with her claim that they were dear friends? How could she declare herself an expert on Emily when Emily had refused to have anything to do with her? Mabel’s solution was to portray Emily as a weird recluse. Not as someone who refused to engage with her brother’s mistress.

Austin Dickinson

Meanwhile, Austin died, and Lavinia claimed to be heir to all Emily’s poems. She blocked Sue from publishing them.

Austin wanted Mabel to inherit The Homestead and the Dickinson land across Main Street. But as Amherst’s leading citizen he couldn’t exactly put his mistress in his will. So he made Lavinia promise she’d give the property to Mabel. After he died, lavinia changed her mind. Lawsuits followed; Lavinia kept the house until she died in 1899.

The Emily Dickinson Museum

The Homestead then passed on to Sue and Austin’s daughter, Martha Dickinson Bianchi. She leased it until 1916 and then sold it. The owners in 1965 sold it to the trustees of Amherst College, which used it for faculty housing.

The dining room at The Homestead

Martha Dickinson lived in The Evergreens until she died in 1943. She willed the house to her co-editor and later his widow. They preserved it as it was when Sue held her soirees. The house passed on to a trust, which merged with The Homestead trustees in 2003 to create The Emily Dickinson Museum.

The Homestead has since been renovated, though The Evergreens hasn’t. The Homestead has a small gift shop, where you can buy an Emily Dickinson tote bag and a lot of books.

Five Things You’ll Remember from the Emily Dickinson Museum

You don’t have to be an Emily Dickinson fan to find The Homestead and The Evergreens interesting. Students of architecture and gardening will have much to ponder.

Her Writing Desk

Emily mostly wrote at a 17-1/2 inch writing table that stood near her window. Nothing seems to evoke Emily Dickinson’s life so much as a visit to her bedroom, to stand at her desk and to look out at the same hills she used to look at.

Her writing desk is to the right.

The Piano in the Parlor

Emily studied piano and voice, and played church hymns, carols and anthems. She also collected sheet music. When she was 20, she attended a Jenny Lind concert with her father.

Her little square piano can still be played.

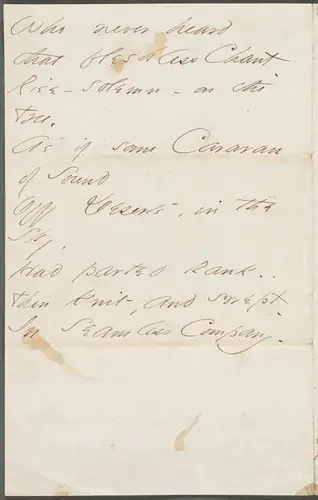

The Pages on Which She Wrote Her Poems

Emily produced a huge volume of letters and poems, and copied many of them as well. The Dickinson family feud that started with Mabel Loomis Todd’s affair with Austin continued after both their deaths. As a result, Emily’s papers have gone to Harvard, to Amherst and elsewhere. But you can see some at the museum.

Her Bed

Just before the 6 p.m. whistle blew on May 15, 1886, Emily Dickinson breathed her last. She had been lying unconscious in her bed, wheezing horribly. Visitors can see the actual bed she died in.

Gravesite

Emily Dickinson fans will recognize her brevity and her wit on her gravestone, just a short walk from The Homestead. It says, “Called Back.”

About Amherst

Amherst is not only a college town, but it’s near the Berkshires’ cultural attractions: Tanglewood, Jacobs Pillow and the Williamstown Theatre Festival.

The Emily Dickinson Museum belongs to the Dickinson Historic District, which includes the old railroad station and the First Congregational Church. Amherst, home to Amherst College and UMass-Amherst, has eight other historic districts. They include the commercial downtown, the Cushman mill village, Millionaire’s Row, an old farm village, Fiddler’s Green and a historic African-American neighborhood.

If you go…

Book a tour of the Emily Dickinson Museum in advance; the hourlong tours fill up fast. The museum is open in 2023 through December 22, and then closes during January and February.

Amherst is a busy college town, so parking can be fraught. Main Street has metered parking, and two parking garages stand two blocks from the museum.

The houses are close to downtown restaurants.

You can also take a virtual visit. Just click here.

With many thanks to Lyndall Gordon for Lives Like Loaded Guns, without which this story could not have been written.

Images: Evergreens: By Daderot. – Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1005308. Dining room: Massachusetts Office Of Travel & Tourism: via Flickr https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/.Emily Dickinson bedroom by Ben Ledbetter, Architect via Flickr CC by 2.0. Homestead (front view) by Bart Everson via Flickr, CC by 2.0. Grave: By Daderot at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18003555.