The long and storied art of handwriting began in the Papal treasury, migrated through Europe to the American colonies, flourished in New England penmanship schools and then died in the internet age.

Handwriting once meant something. For one thing, it meant you could read and write. Back in the day, not everyone who could read knew how to write.

Your style of handwriting also showed who you were. Businesspeople used one style of handwriting, a simple, legible hand. Leisured gentlemen used another with lots of flourishes. Ladies had their own delicate alphabet.

Handwriting, though, didn’t just evolve as a generally accepted thing. Over the centuries, a handful of individuals, fanatic about penmanship, set handwriting standards for most of the rest of us. They decided what a capital X should look like, at what degree letters should be angled, the loopiness of lower-case letters.

Then, of course, the keyboard and the screen made handwriting disappear. But devotees of pen and ink should take heart. Handwriting may be coming back.

An essential skill

For centuries, legible handwriting was an essential skill for businesspeople and government officials. Laws, deeds, proclamations, contracts and military orders all had to be recorded somehow. But without a standard, different penmanship styles were like different languages.

Writing masters in the papal treasurer’s office first developed an italic cursive script that morphed into the handwriting taught to American schoolchildren in the 20th century. After the sack of Rome in 1527, the pope’s writing masters moved to Southern France. But without the Roman Catholic Church enforcing handwriting discipline, they began to come up with new styles of writing alphabets.

The Italic cursive evolved into italic circumflessa, which further evolved into a French style called rhonde.

French government officials complained they couldn’t read documents because they were written in different hands. The Controller-General of Finances then decided all legal documents had to be written in one of three handwriting styles: the coulee, the rhonde and the speed hand.

The French rhonde migrated to England, where it developed into the English round hand.

A Handwriting Giant

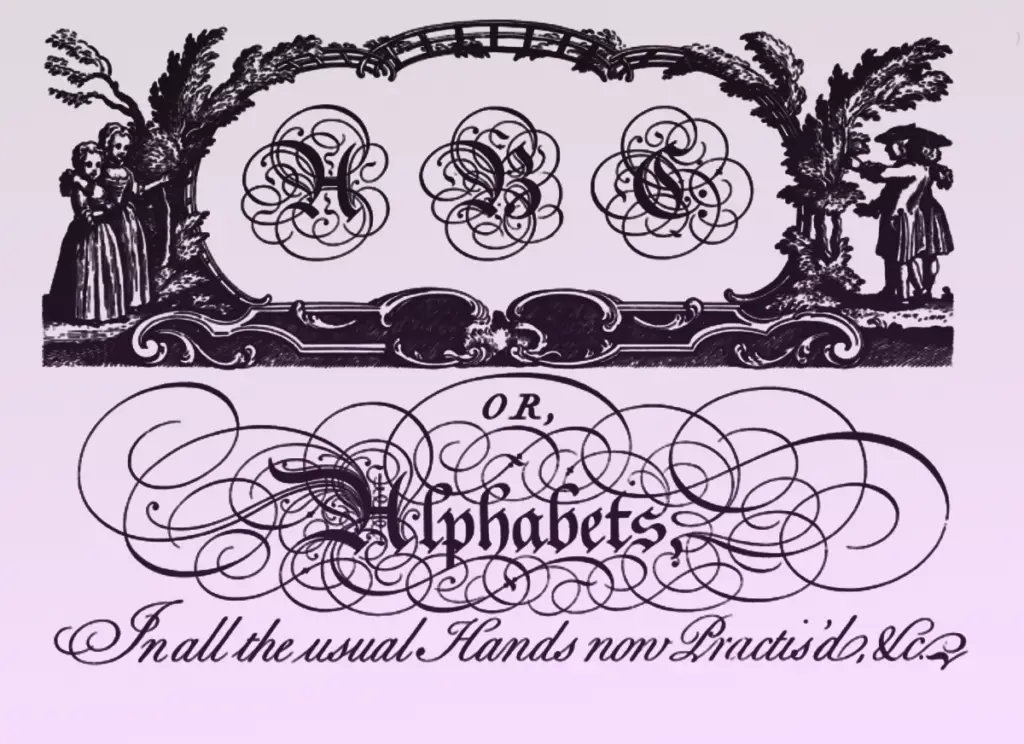

George Bickham, a giant in the pantheon of penmen, was a key figure in the development of handwriting. A calligrapher and an engraver, in 1733 he collected samples of penmanship from 24 writing teachers in London. He engraved them and published them in a book, The Universal Penman.

The book had 19 complete alphabets, such as Gothic, which was falling out of fashion except for legal documents. Bickham’s book – still available, on Amazon — popularized the new English round hand. It looks like a typeface known as Copperplate.

Bickham had an alphabet for everyone, or at least anyone who needed to write. There were alphabets for English gentlemen, alphabets for merchants, alphabets for women and girls.

Handwriting Schools

Like many other things, the English round hand crossed the Atlantic to the colonies. Writing masters taught the English round in writing schools, or they traveled the countryside like peddlers looking for pupils.

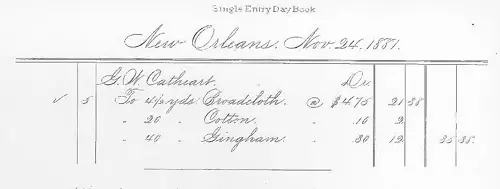

Boston had three writing schools by the time of the American Revolution. They taught more boys than the better-known Latin School. The curriculum was narrow: boys were taught math and penmanship so they could produce dignified-and readable documents. If you wanted to be a merchant, bookkeeper, legal clerk or engrosser, you needed to have decent handwriting.

It wasn’t easy. You had to know how to make a quill from a goose feather, mix ink, rule lines on paper or parchment and write without spotting or smudging the writing surface. You had to know how to sit or stand, what angle to position the paper and how to hold the pen.

John Tileston taught at Boston’s public writing school in the North End for 65 years. He had an injured hand and probably inspired the fictional character Johnny Tremain. Tileston was also a good friend of John Adams, who needed legible handwriting for legal complaints, letters to Abigail and founding documents of the United States of America.

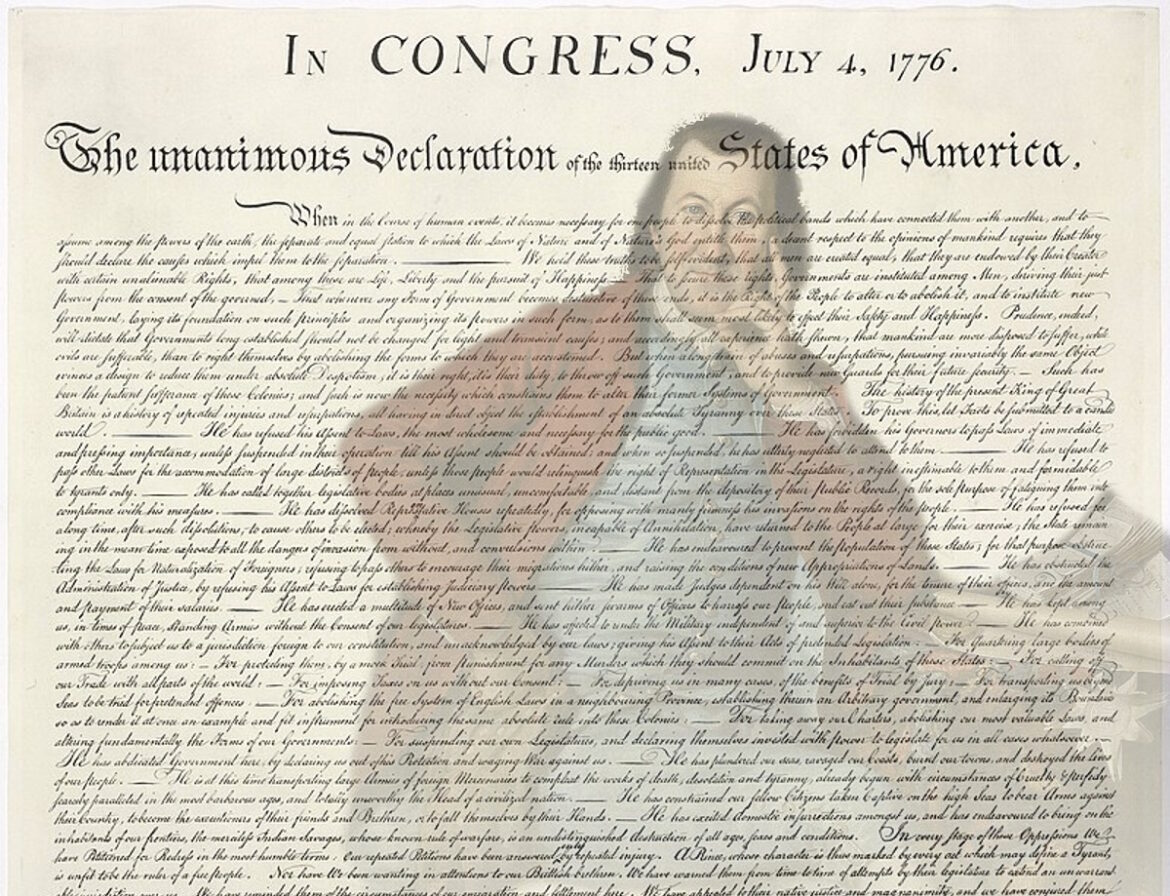

Declaration of Independence

It was Adams’ friend Thomas Jefferson, of course, who drafted the Declaration. He had a neat round plain hand, but he didn’t actually write the document. A Pennsylvania brewer, Timothy Matlack, known for his excellent handwriting, was tasked with the project.

Timothy Matlack

Matlack didn’t sign the Declaration, even though he wrote it. He wasn’t a delegate. But he did fight in the American Revolution, leading Pennsylvania’s 5th Rifle Battalion across the Delaware with George Washington.

Spencerian Handwriting

Handwriting changed along with writing instruments and the reason for writing. English round hand, for example, came about partly because people started using more flexible nibs. The Spencerian script spread as people began using steel pens. Telegraph operators adopted the Spencerian script because they needed a faster, simpler handwriting than the English round hand in order to transcribe Morse code.

From the 1860s into the early 1900s, Spencerian handwriting dominated the written word in America. Platt Rogers Spencer invented it in 1840 by simplifying the English round hand. His capital letters didn’t require the pen to be lifted from the paper so much, and lower-case letters were more angular.

He opened a school in Jericho, N.Y., to teach his system of handwriting and record-keeping. His students went on to found the chain of Bryant & Stratton business schools, which spread Spencerian handwriting in factories, mills and warehouses throughout America. He also taught Penmanship at the Enterprise Institute in Hiram, Ohio, under President James A. Garfield, who later became U.S. president. Garfield wrote the introduction to his book, the Spencerian Key to Practical Penmanship. He called Spencerian script “the pride of our country and the model of our schools.”

Spencer came up with a ladies’ hand, too.

After the Civil War, it became the American standard writing style for business correspondence and for government clerks. Henry Ford learned the Spencerian style of handwriting; you can see it in the Ford Motor Company logo. Coca Cola’s bookkeeper also used the Spencerian script to design the company’s trademark.

Palmer Method of Handwriting

Good handwriting could get you a good job. G.A. Gaskell taught Spencerian handwriting at a Bryant & Stratton business school in Concord, N.H. He ran a newspaper ad for the school saying hundreds of his students, “who by means of their elegant penmanship secured through his instruction, now occupy important and lucrative positions.”

Austin Palmer worked as a janitor to pay his tuition at Gaskell’s school. Sure enough, he got a job as a bookkeeper and clerk in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Palmer watched his colleagues toil away at their writing all day. Spencerian handwriting had too many curls and flourishes, he thought. It also required too many lifted-arm movements. It was too tiring and too slow, and at the end of the day it gave a clerk a sore arm.

Palmer penmanship

He decided to turn handwriting into “rapid, plain, unshaded, coarse-pen, muscular movement writing,” as he put it.

Muscle Memory

He came up with the idea of muscular movement. Palmer insisted writers use their forearm and hand to move the pen rather than fingers. He believed in muscle memory—if muscles moved in the same pattern over and over, those movements would be imprinted on the brain and become habit.

Palmer quit his job and taught penmanship, while starting the first handwriting magazine, The Western Penman.

He subjected his penmanship students to tedious drills in which they had to quickly repeat the same spiral and wave marks hundreds of times. Palmer also viewed left-handedness as deviant and made all students write with their right hand.

Catholic schools adopted his method first, liking its emphasis on discipline and hard work. Then Palmer demonstrated the Palmer method at the St. Louis Exposition, where it impressed a New York City school superintendent. Soon half the students in New York City were learning the Palmer method. When Palmer died in 1927, 75 percent of the schools in America taught the his method.

After Palmer

Twentieth-century child psychologists figured out that small children, especially boys, did not have the fine motor skills to master cursive writing. By the 1950s, the Palmer method began to fall to the Zaner-Bloser method, which taught children to print their letters before learning cursive.

Then after 1976, schools adopted the D’Nealian method. Educators thought it made it easier for children to transition from print to cursive.

When the internet came along, educators pretty much abandoned teaching penmanship altogether. In 2010, cursive was removed from the federal Common Core Standards for K-12 education. The group that created the standard decided the need to learn to keyboard became more important.

Then parents began noticing their children couldn’t sign their own name when they applied for passports or endorsed checks. The pendulum began to swing back. In 2023, Connecticut changed course and restored the requirement that schools teach cursive writing.

Thanks to Handwriting in America by Donna R. Braden at the Henry Ford blog.

Images: Timothy Matlack by By Charles Willson Peale – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, online database, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4023540.