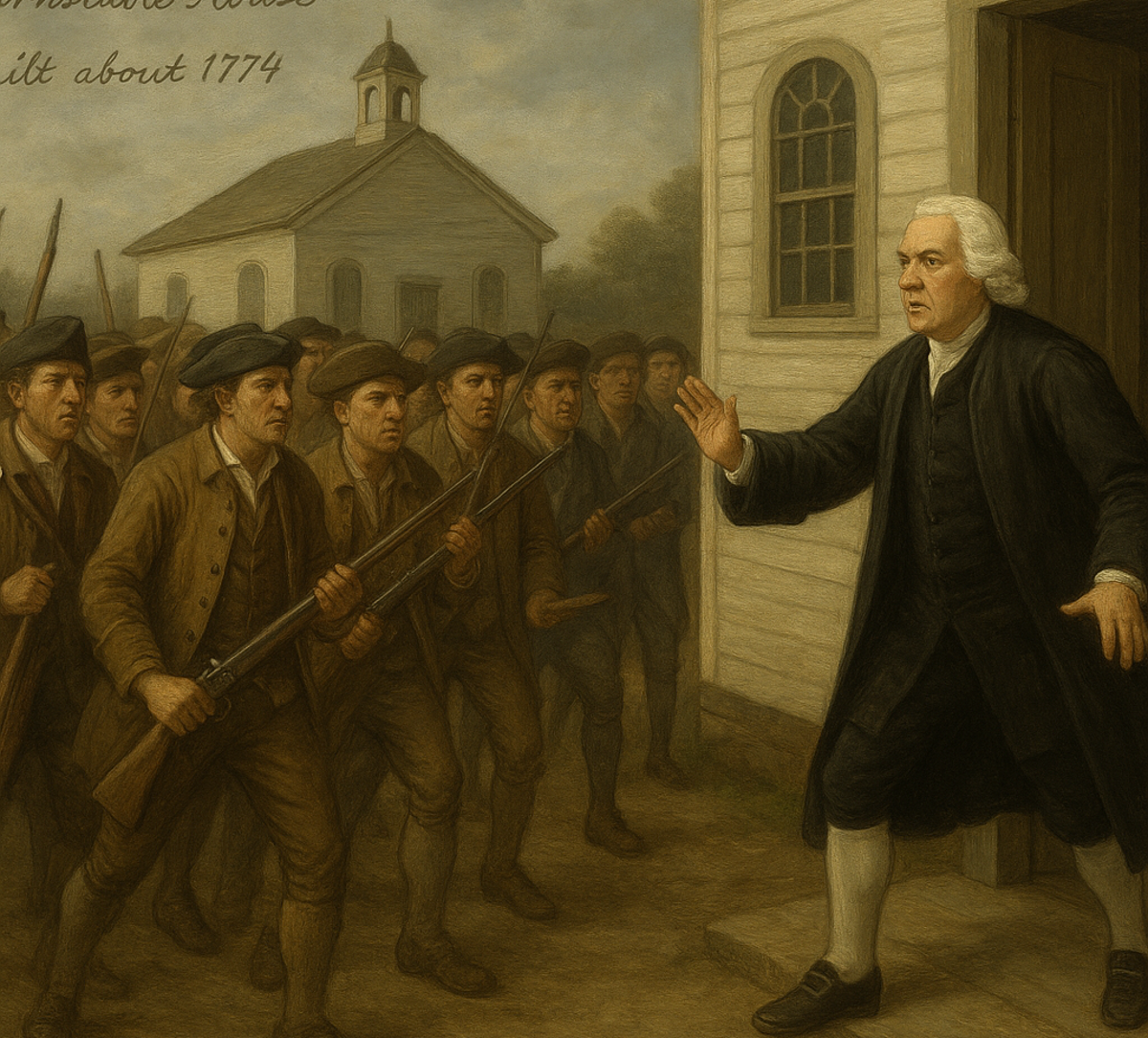

In the fall of 1774, Massachusetts farmers won a revolution before the first shots at Lexington and Concord. While every American fifth-grader knows about the shot heard ’round the ![]() world, almost no one knows the story of the nearly bloodless uprising that freed the colony from British control outside of Boston. This is the story of the Forgotten Revolution — an organized and decisive overthrow of the Crown’s authority. American history, however, has nearly forgotten it.

world, almost no one knows the story of the nearly bloodless uprising that freed the colony from British control outside of Boston. This is the story of the Forgotten Revolution — an organized and decisive overthrow of the Crown’s authority. American history, however, has nearly forgotten it.

The British Parliament lit the spark in London. Furious over the Boston Tea Party, the lawmakers passed the Coercive Acts to punish and isolate Massachusetts. The most devastating of these was the Massachusetts Government Act. It decreed that the people would no longer elect judges, sheriffs and Governor’s Councilors. Instead, the royal governor — Gen. Thomas Gage — would appoint them. The law also banned Town Meeting except for once a year. The patriot propaganda machine called it an attempt to impose “abject slavery” on the people of Massachusetts.

For the plain folk of the colonial countryside, this was an existential threat. The courts of Common Pleas met four times a year, and they mostly adjudicated unpaid debts. They had the power to seize property as a remedy.

Now, a judge appointed by the Crown, not answerable to the community, could seize on small debts to foreclose on their farms. The colonists feared the Crown-appointed judges would use the law to reduce them to serfdom. Invisible hands across the Atlantic would strip them of their independence.

The Forgotten Revolution

When the new law took effect on August 1, 1774, the people were ready. They had armed themselves and drilled on town greens. Then, in an unprecedented uprising, tens of thousands of plain folk from the Berkshires to Cape Cod rose in mostly peaceful resistance. They gathered by the thousands at meeting houses, resolved to close the courts and force the newly appointed judges, sheriffs barristers and justices of the peace to resign. Throughout the colony, they forced the courts to close. They also intimidated the newly appointed governor’s councilors, including the lieutenant governor, to resign. And they held Town Meeting with impunity — in Salem, right under Governor Gage’s nose.

By the end of September, the British government’s authority in Massachusetts outside of Boston had ended. Few plaques mark most of these events, no grand reenactments of the day a kingdom’s power was dissolved by the will of its people. But for a month, the farmers, tradesmen and common citizens of Massachusetts won their independence from Britain. This is the story of their forgotten revolution.

Worcester Beginnings

On Sept. 6, 1774, the Court of Common Pleas for Worcester County was due to convene at the meeting house (now City Hall). The king’s newly appointed judges arrived to find Main Street lined by nearly 5,000 militiamen from 37 different towns — half the county’s adult male population. The protesters proclaimed that the Courts should not sit on any terms.”Then they humiliated the court officers, forcing them to walk back and forth 30 times, hats in hand, repeating that they resigned and would not open the courts

The people of Worcester County then set up their own government. They freed all prisoners charged with debt, fired any public officials who wouldn’t resign, stopped send tax revenue to British authorities in Boston and established seven new militia regiements.

Royal Gov. Thomas Gage had seen it coming, but he couldn’t do anything about it. He wrote to Lord Dartmouth , Secretary of State for the Colonies, telling him that in Worcester County the colonists openly threatened armed resistance, bought gunpowder and guns and cast ammunition.

The Forgotten Revolution Spreads

The rebellious colonists coordinated their response to the Massachusetts Government Act, and the forgotten rebolution spread to Springfield, Great Barrington, Plymouth, Cambridge, Tauntaon and Barnstable.

On Sept. 6, 1744, several thousand protesters and armed militia marched to the Springfield meeting house, so crowding it the judges couldn’t sit down. They then forced th court officers to take off their hats and sign their resignations. An eyewitness described the scene:

The people of each town being drawn into separate companies marched with staves & musick. The trumpets sounding, drums beating, fifes playing and Colours flying, struck the passions of the soul into a proper tone, and inspired martial courage into each.

Earlier in Great Barrington, 1500 unarmed men filled the meeting house and the roads leading to it on Aug. 24, 1774. They prevented the judges from entering the building and forced their to resign. They also forced one of the king’s justices of the peace to flee from his home to Boston for safety.

The same thing happened in Concord, where so many people filled the meeting house the newly appointed judges, barristers and sheriff couldn’t get in. The court officials repaired to Wright’s Tavern, and offered a compromise: If they could enter the building, they wouldn’t conduct any business. Their answer came at sundown: No.

On Sept. 27, 1774, the new lawyers and justices tried to open the Court of Common Pleas in Plymouth. They had as much luck as the others. As many as 3,000 militiamen and protesters blocked the courthouse and forced the court officials to publicly resigm.

A Cape Cod Family Affair

James Otis, Sr., accepted a royal appointment as presiding justice of the Barnstable County Court of Common Pleas on Cape Cod. But the patriots of Cape Cod viewed the royally appointed court officers in the same light as those in the rest of Massachusetts.

According to “The History of Barnstable County,”, the residents of Sandwich, joined by many from the towns west, marched to Barnstable to intercept the sitting of the court of common pleas.

The chief justice, Col. James Otis, Sr., addressed the crowd, “As is my duty, I now, in his Majesty’s name, order you immediately to disperse.”

Nathaniel Freeman, the leader of the p rotest, replied, “We thank your honor for having done your duty, we shall continue to perform ours.”

In the end, all the Crown-appointed judges in Barnstable County agreed they would ignore Parliament’s new law.

Some accounts claim the crowd was led by James Otis, Jr.,the ardent patriot who coined the term “taxation without representation.” But James Otis, Jr., suffered from mental illness and was probably quite mad by then. But two of the judge’s other sons, Joseph and Solomon, did participate in the protest. His daughter, Mercy Otis Warren, also supported the patriot cause and wrote the first (ck_ history of the American Revolution. Her statue and her famous brother’s both stand in front of the new stone Barnstable County Courthouse.

The Forgotten Revolution in Taunton

Taunton, a hotbed of patriotism, took the rebellion a step further. People from the surrounding towns met in Taunton and adopted a resolution against the “pretended authority of the British government.” They then attacked the house of Daniel Leonard, one of his majesty’s justices of the Peace and a barrister. Leonard had to flee for his life when they fired bullets into his house. Peter Oliver, another of the king’s justices of the peace, was driven from his home in Middleborough fled to Boston.

A month later, Taunton’s Liberty and Union flag was unfurled on the town’s green – the town’s own declaration of independence.

James Otis, Jr., by Henry Blackburn

Executive Council Wiped Out

For Royal Gov. Thomas Gage, the rebellion in the towns took away his government — not just his judges, sheriffs and barristers, but also his Governor’s Council. The Council performed vital government functions as the upper legislative body and the highest court in the colony. The Massachusetts Government Act changed the Governor’s Council from an elected to an appointed body.

But the patriots intimidated most of them into resigning or refused to take office.

Gage had appointed Thomas Oliver of Cambridge as his lieutenant governor. Oliver soon wished he hadn’t. Four thousand men attacked Oliver in his house, forcing him to resign. That didn’t pacify the patriots, who forced him to flee to Boston for protection.

The House of Representatives, which remained intact under the law, refused to recognize it and formed their own hadow government–the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. The Provincial Congress essentially replaced British authority. It began collecting taxes, regulating trade, organizing militia units and buying military supplies. For the first time, an American colony had created a fully operational, independent government that ignored royal authority.

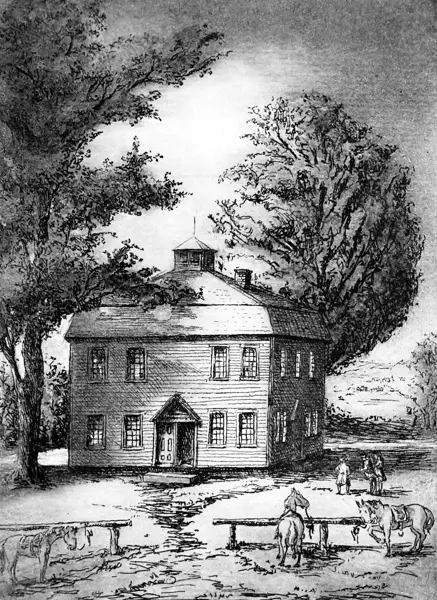

Not Forgotten in New York

Months later, the people of Westminster, Vt. , took over the county court after a bloody confrontation. The town then belonged to New York Colony. On March 13, 1775, tensions between local patriots and Loyalist officials came to a head in the Cumberland County courthouse. Patriots, fearing economic ruin and the seizure of their farms by Loyalist courts, had occupied the building to prevent a session. Despite a promise from the chief judge that they would be unmolested, an armed posse led by the sheriff arrived and fired upon the protesters, who were armed only with sticks. One young farmer, William French, was mortally wounded and tormented as he died in a cell.

By the next morning, over 400 patriot militiamen had surrounded the courthouse, forcing the surrender of the officials inside and effectively ending New York’s authority in the region a full month before the battles of Lexington and Concord. While New York’s governor decried the event as a “dangerous insurrection,” the outbreak of wider revolution soon overshadowed it.

The Westminster Massacre, though largely forgotten, is considered by many Vermonters as the first bloodshed of the American Revolution.

* * *

Learn more Revolutionary history in this complete guide to Revolutionary War Sites in New England. Brought to you by the New England Historical Society. Click here to order your copy in paperback, here to order an ebook.

With thanks to Ray Raphael, “A People’s History of the American Revolution.”

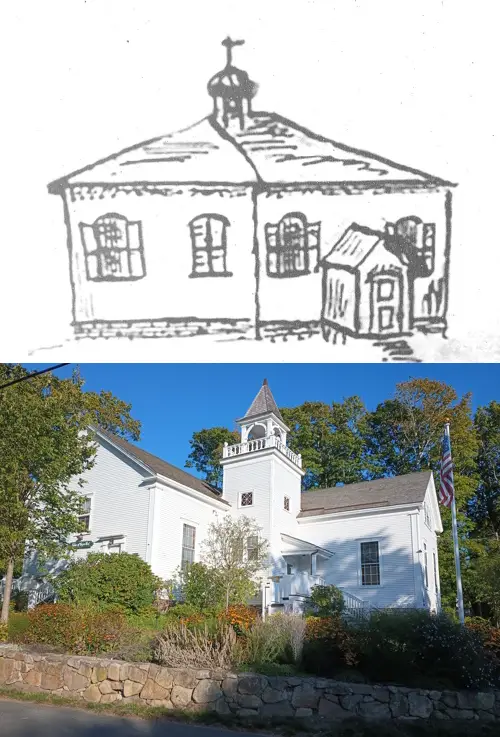

Images: Featured image created by ChatGPT. Image of the Westminster meeting house courtesy Jesse Haas, president of the Westminster Historical Society.