The Westminster Massacre went from “dangerous insurrection” to forgotten incident in less than six  weeks. But March 13, 1775, is still considered by many Vermonters to be the first bloodshed of the American Revolution.

weeks. But March 13, 1775, is still considered by many Vermonters to be the first bloodshed of the American Revolution.

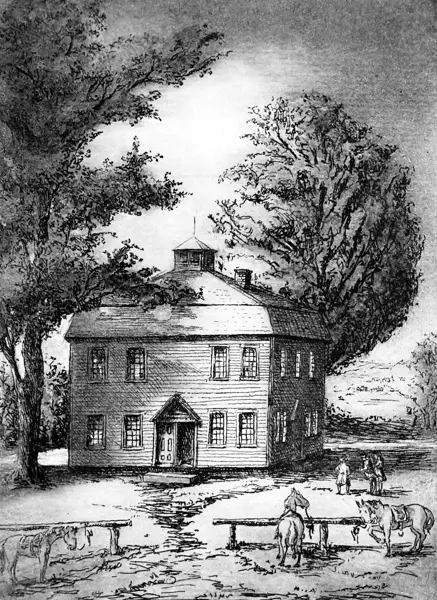

Westminster, though settled mostly by people from Massachusetts, was then part of Cumberland County, New York — present Vermont east of the Green Mountains, from Tunbridge to the Massachusetts border. It was a humble place, just a scattering of log cabins, taverns and a courthouse.

1774 had been tumultuous. In retaliation for the Boston Tea Party, Britain had replaced elected magistrates in Massachusetts and forbidden town meetings. Enraged, thousands of farmers armed with sticks closed every Massachusetts court. Meanwhile the Continental Congress passed a trade embargo against Britain. It was ratified by all the colonies except New York.

Cumberland County towns voted to support the embargo, and “be it right or wrong . . . to assist the people of Boston in defense of their liberties.” Now what? They faced economic ruin, as other colonies enforced the embargo against noncompliant New York. Also, the local court officials, all Loyalists, were taking advantage of the turmoil to seize patriots’ farms through bankruptcy proceedings. To make their loyalties clear and to prevent the courts from seizing their farms, Cumberland County patriots decided to close down the court at Westminster.

Westminster Courthouse

A Little Visit

The court session was due to start on March 14, a Tuesday. On March 10, 40 patriots visited chief judge Thomas Chandler at his home. They asked him to close the court. He said he had a murder case to try on Tuesday, but if the patriots would meet him at court they could discuss it

The patriots feared that Sheriff William Paterson would bring arms against them. Chandler promised that wouldn’t happen. But the moment the patriots left, he sent messages to his fellow Loyalist officials. They decided to get to the courthouse on Monday and shut the patriots out of the building.

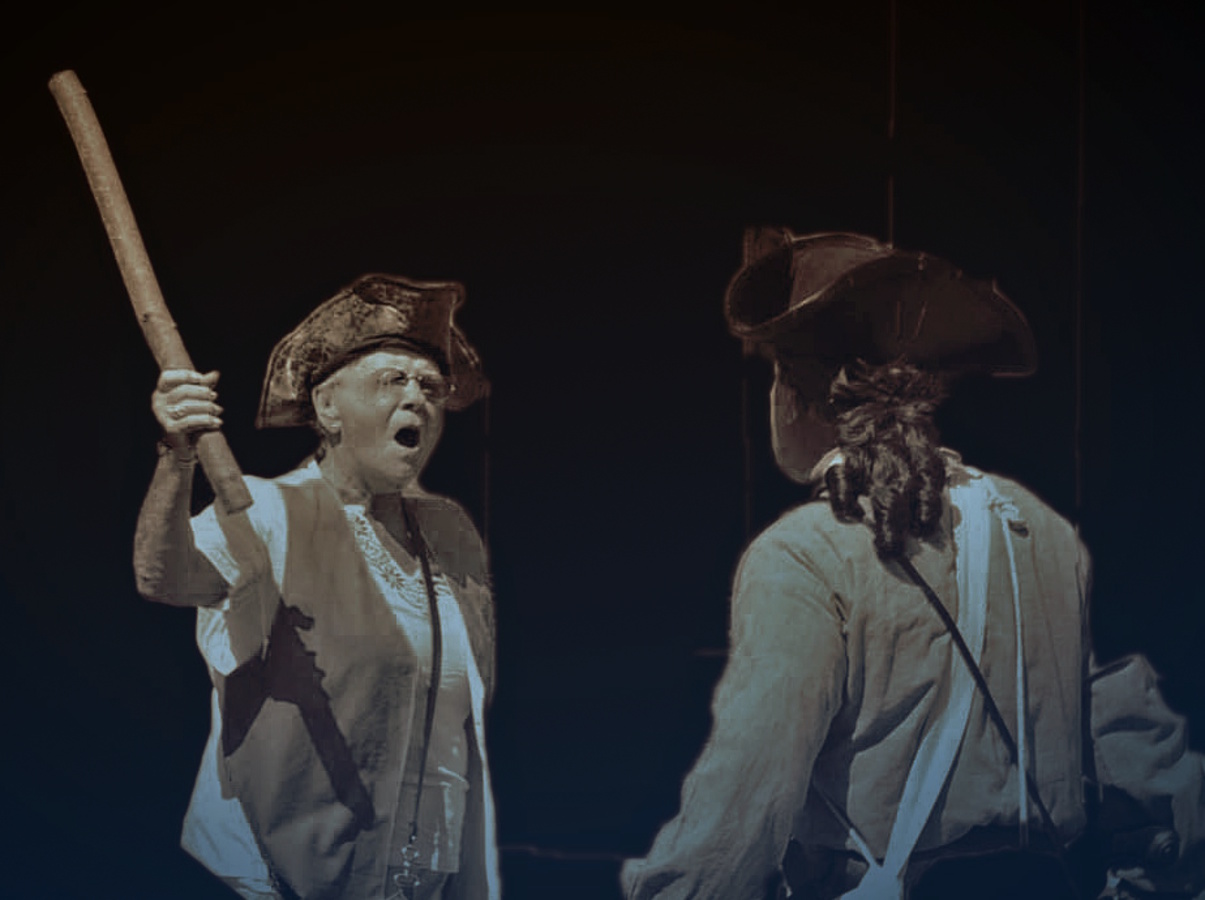

Drum used by patriot militia

Getting wind of this, 100 patriots converged on the farm of Westminster militia captain Azariah Wright on Monday, March 13. They armed themselves with sticks from his woodpile and occupied the courthouse. Twenty minutes later Sheriff Paterson arrived at the head of a 75-man posse, which included the Loyalist court justices. Despite Chandler’s promise, many were armed with muskets, swords and pistols. Paterson read the Riot Act; the protesters defied him and Paterson promised to “blow a lane” through them.

When Judge Chandler reached the courthouse late in the day, Captain Wright reminded him of his promise. Chandler vowed to take the posse’s guns away. He promised that the protesters could occupy the courthouse unmolested overnight.

But Chandler did not confiscate the weapons. The Loyalists retired to the nearby Tory Tavern to drink and lay their plans. Meanwhile the patriots drew up a list of demands, then settled down for the night, leaving guards at the doors.

The Westminster Massacre

At around 11:30 p.m. a guard spotted moonlight gleaming on a musket barrel at the east door of the courthouse. “Man the doors! Man the doors!” The patriots crowded out onto the step, armed only with sticks. The sheriff marched his posse close and roared, “Fire, god damn ye, fire! Send them to hell!”

The volley hit several protesters point-blank. According to the patriots’ report, written a few days later: “There were several men wounded; one was shot with four bullets, one of which went through his brain, of which wound he died the next day. Then they rushed in with their guns, swords and clubs, and did most cruelly mammock several more; and took some that were not wounded, and those that were, and crowded them all into close prison together, and told them that they should all be in hell before the next night, and that they did wish that there were forty more in the same case with that dying man. When they put him into prison, they took and dragged him as one would a dog; and would mock him as he lay gasping, and make sport for themselves at his dying motions.”

The dying man was William French, a young farmer from Brattleboro. As posse members tormented him, Captain Wright sent riders to alert militias in neighboring towns. By morning French lay dead on the floor of the cell. Upstairs in the courtroom, the officials wrote up a whitewashed version of events.

Aftermath of the Westminster Massacre

Meanwhile, in Westminster’s one street, over 400 patriot militiamen gathered. Now they had their guns! They threatened to burn down the courthouse or shoot everyone inside. Capt. Benjamin Bellows of Walpole, commanding the New Hampshire militias, positioned his men around the courthouse to prevent more violence.

Late in the afternoon, two patriot leaders simply walked into the courthouse and persuaded the court officials to surrender. They were put in the cells, thus ending New York and British government in Cumberland County a month before Lexington and Concord.

The New York Assembly voted money to put down the rebellion. Acting Gov. Cadwallader Colden wrote to Lord Dartmouth of the “dangerous insurrection in Cumberland County.” But before his April 5 letter reached England, Lexington and Concord ignited revolution.

Nowadays people sometimes snicker at a “massacre” with only two deaths. But to the people who experienced it, the indiscriminate killings after months of peaceful protest were shocking. The events at Westminster were being called a massacre by the following day. Loyalty to New York and the Crown were shaken, and neither government was ever restored in what is now eastern Vermont.

The Westminster Historical Society will commemorate the Westminster Massacre with 3 events March 13-15. Details at www.westminstervthistory.org.

Jessie Haas is president of the Westminster Historical Society.