The worst train wreck in New Hampshire history started in the predawn hours of September 15, 1907. The Quebec Express gently pulled out of the station at White Fiver Junction, Vt. at 3:55 a.m. bound east for Concord.

On the same track, 18 miles away at the Canaan, N.H. station, freight train no. 267 had arrived roughly on schedule at 4:10 a.m. A telegraph message waiting at Canaan informed 267’s operators that the Quebec Express wouldn’t even be departing White River for at least another fifteen minutes. That left plenty of time for the 267 to make it to West Canaan – four-and-a-half-miles away – and pull onto a sidetrack to allow the Express to pass by.

Thinking nothing was out of the ordinary, the crew of the 267 put the train in motion – unaware that the Quebec Express was actually already barreling down the same track heading straight at them.

Moments later James Browley, the train dispatcher from Concord, telephoned the Canaan station. He wanted to relay another bit of information: The crew on 267 should know a light on the track in Lebanon was broken. Canaan telegraph operator John Greeley informed Browley that the 267 had already left, headed toward White River.

Browley knew in an instant that, barring some tremendous stroke of luck, the crew of the 267 was steaming head long into a catastrophe. And why on earth had they departed the station? The reality would make Browley’s blood run cold: The train had departed because he himself had told them it was safe to proceed.

The Sherbrooke Fair

Most of the 150 passengers on the Quebec Express that morning had started their journey the night before when they boarded the train at Sherbrooke in southern Quebec.

They settled into their seats and sleeping compartments and drifted off, happily weary from hectic days spent at the Sherbrook Fair.

The Sherbrooke Fair was always popular with local residents, but the 1907 fair was even larger than usual. That year the Canadian government designated Sherbrooke to host the annual Dominion Exhibition – an annual event sort of like a one-country world’s fair that highlighted the region’s businesses and history. For two weeks the fair hosted horse races, vaudeville shows, exhibitions by aviation pioneer Lincoln Beachy and nightly firework displays depicting the 1902 volcanic eruption of Mount Pelee on Martinique.

For French Canadians living in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, the fair represented a wonderful occasion to head north for a family reunion and a celebration of their former homeland.

After the excitement of the fair, the Quebec Express, consisting of a locomotive and just four cars – baggage car, passenger coach, smoking car, and a Pullman car (the equivalent of first class), carried its passengers back toward their homes in places like Manchester and Nashua and Lowell, Mass.

The Freight Train

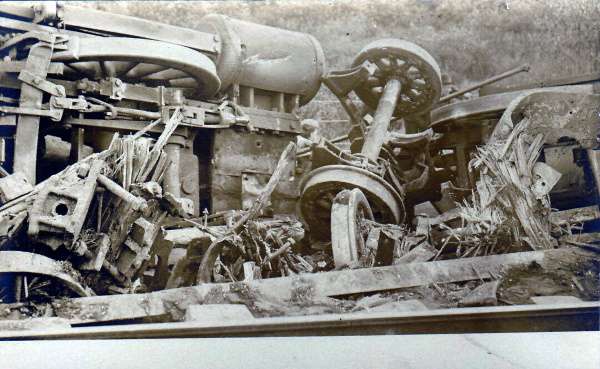

The worst train wreck in New Hampshire history.

The 267 freight train dwarfed the Express. Twenty-seven cars made up the 267, 21 of them fully loaded on that fateful day. Printer’s paper, corn meal and much more was stuffed into the box cars that trailed behind the 267. It weighed in at 770 tons in all. A train of that size could easily take a half a mile or more to stop once the brakes were applied.

As the two trains approached a 3,600-foot straight stretch of track at Kendrick’s meadow in Canaan, the freight train travelled at 25 miles per hour, the Quebec Express five to ten miles per hour faster. This long, straight stretch of track offered the last chance for the trains to avert catastrophe. On a clear night, the train crews could have seen each other’s lights and braked, if not averting a crash, at least minimizing the damage.

But on the morning of September 15 a thick fog had settled in. Moisture had coated the train tracks. With 300 to 400 feet separating the two trains, the crews finally caught sight of one another as the lights of the trains cut through the fog. Engineers on both trains immediately cut steam power and applied emergency brakes. Powerless to do anything more, the engineers and firemen from both trains jumped off the moving trains – as they were trained to do. Miraculously they suffered no injuries.

With no one at the controls for the final seconds of their journey, the two trains hurtled toward each other, the slick tracks minimizing any slowing effect the brakes might have had.

Worst Train Wreck in New Hampshire

Bodies Removed From the Train

Inside the Quebec Express, passengers mostly slept. The journey had been uneventful. At about 20 minutes past four, someone in the train’s passenger car had unexpectedly begun singing. Three men, awakened and, mildly irritated by the singing, decided to move to the smoking car toward the rear of the train. The decision probably saved their lives.

The wreck itself, at 4:26 a.m., was fierce and brief. Both engines derailed and the loss of life and most of the injuries were caused by the baggage car telescoping into the passenger car behind it. That is, rather than buckling or falling to the side on impact, the jolt pushed the baggage car through the passenger car like a piston, and it obliterated the passengers on one side of the car.

Within moments, the railroad crews who had jumped off the trains ran to assist. A conductor headed back up the line to warn the Montreal express – the next train coming – to stop. Notice was sent to Enfield, from a nearby home, as well as Concord to the East and Hanover to the West that medical help was needed. Teams of rescuers assembled and boarded trains to reach the scene.

Passengers Tell of The Crash

At the crash scene, survivors began trying to extricate the injured passengers from the train. They described a shocking scene of body parts strewn about and mangled passengers pinned under benches and steel beams that made up the train.

Charles Clark told the Canadian newspaper La Presse that he was among the survivors able to render aid to other passengers.

“I was sitting in the smoking car when the shock occurred. I was partially thrown out of a seat and ended up coming out completely. It was dark and the night was covered with a thick fog, the only light that lit the scene came from the hearth of the express locomotive.”

“I left the car. Had an injured left hip and back; Cut my arm terribly while trying to get out of the car . . . I felt dizzy for a few minutes. I could hear the moans of those trapped inside the car.

“At this point the engineer of the express train introduced himself and called for help; it was a matter of rescuing the injured and removing the dead from the debris.

“For my part, I did everything in my power to help the many unfortunate people who lay helpless under the wreckage of the twisted and torn cars. Once we had opened the boot where the rescue tools were, we made a hole in the roof of the car; a number of victims spread out, caught between the benches, the beams of the different parts of the half-demolished car.

“The passengers were in despair and offered us watches, jewels, precious objects, money to withdraw them from their terrible position. A woman appearing very old had a terribly mutilated leg, caught between the benches and a beam. She begged us to not move her and go rescue her sister instead. In several cases, we had to break limbs in order to get the wounded out of their awful situation.”

Bodies Strewn Everywhere

Charles Pascal was luckily in the smokers’ car toward the back of the train. The crash knocked him momentarily senseless, but he recovered and assisted in the rescue. The sights shocked him. A mother with her dead child. A boy who had lost an arm. Some passengers remained pinned under benches for over an hour before rescuers could remove them.

A Mr. Bouchard, who was also in the smoking car, reported he was stunned as he searched among the dead and wounded. “A dead woman had by her side a lovely 2-year-old baby talking to her; the child believed her mother was asleep. The father was mortally wounded, and he begged me to carry the child to the sleeping car, a service I hastened to do. The child didn’t have a scratch.”

Another recalled talking just moments earlier with passengers Bridget and Timothy Shaughnessy, newlyweds from Manchester, N.H. returning from their Canadian honeymoon.

“Mrs. Shaughnessy said that she had a dream during the night and that she had seen the train enveloped in flames.” Both the Shaughnessys perished in the crash.

Miraculous Survivals

Among the horrors there were also miraculous stories of survival as well.

Cleophas Belanger had planned to take the train but detoured to spend a day at Weirs Beach in New Hampshire. He had to telephone to worried family when he learned of the crash.

Passenger Frank Webster had a seat in the passenger car that suffered the worst damage. The force of the crash catapulted him out a window, but he suffered no injuries.

Several passengers moved to the smoking car just moments before the wreck, and they walked away unscathed. E.M. Pettis’ luggage had been placed on the train, but he was delayed and had to catch a later one. Another passenger had to wait because she felt too sick to travel.

As Sunday progressed, the railroad workers gradually cleared the wreckage from the rails. Trains carried the injured to Hanover and south to Concord, Manchester and Nashua. A funeral home in Concord took charge of most of the bodies, storing them until families could come identify and claim them.

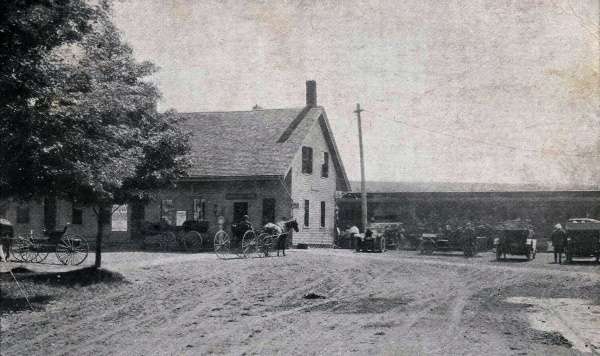

Anxious Trains Stations

Canaan train station, the freight train’s final stop before the worst train wreck in New Hampshire history.

News of the train wreck had spread like wildfire through the French Canadian community in New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Down the Merrimack River Valley in the mill cities of Manchester, Nashua and Lowell, anxious crowds thronged the rail stations for news. Bulletins about the crash had spread the first news quickly to New England’s Little Canada neighborhoods, but little information came out about who had and hadn’t perished.

At train stations, shouts and applause rang out as survivors emerged from trains, greeted by worried family and friends.

A crowd numbering in the thousands packed the train station at Lowell, and ambulances stood by for any injured. But the ambulances quickly left when it became clear the injured had all been taken care of in Manchester and Nashua. Travelers quickly reunited with their families and returned home.

As more and more passengers joined up with their families, those less fortunate had had to face the task of finding their missing relatives, either among the wounded in hospitals or among the dead.

Picking Over The Ashes

Rescuers pulled 25 dead bodies in all from the train wreck: Mrs. W. E. Warren. Bridget Shaughnessy, Timothy Shaughnessy, Leon S. Cady, Delia Hould, Fred M. Phelps, Annie St. Pierre, Richard F. Clarkson, George L. Southwick, T. Howard Warren, Mrs. Lethra C. Blake, Lillian Vintinner, Dominick, Benoit, Frank H. Lower, Vena Gagnon, Alice Cunningham, Mrs. Adolph Boisvert, Annie Barrett, Augustine Boyer, C. E. Derby, Mrs. William Vintinner, H. D. Stevens, Malcolm N. Wilson, Mrs. E. S. Griggs, and John H. Congdon. Eighteen others suffered serious injuries, including one that turned out to be fatal.

Rescuers pulled 25 dead bodies in all from the train wreck: Mrs. W. E. Warren. Bridget Shaughnessy, Timothy Shaughnessy, Leon S. Cady, Delia Hould, Fred M. Phelps, Annie St. Pierre, Richard F. Clarkson, George L. Southwick, T. Howard Warren, Mrs. Lethra C. Blake, Lillian Vintinner, Dominick, Benoit, Frank H. Lower, Vena Gagnon, Alice Cunningham, Mrs. Adolph Boisvert, Annie Barrett, Augustine Boyer, C. E. Derby, Mrs. William Vintinner, H. D. Stevens, Malcolm N. Wilson, Mrs. E. S. Griggs, and John H. Congdon. Eighteen others suffered serious injuries, including one that turned out to be fatal.

The B&M promised answers and 23 witnesses, mostly railroad personnel, testified at the accident investigation inquiry.

It soon emerged that the Quebec Express had left on the approved schedule. That meant the 267 freight car had left Canaan when it should not have.

From the start there were only three possible explanations. The dispatcher at Concord, Browley, had erroneously instructed the 267 freight train to proceed. The telegraph operator at Canaan, Greeley, had provided the 267’s crew with incorrect information. Or some combination of errors on both men’s parts had caused the crash.

In the end, the inquiry concluded that Browley, the dispatcher, erred. He had sent a telegraph message that the Quebec Express would run one-hour-and-ten minutes late. Actually, the Montreal Express – the next train coming – was running one-hour-and-ten minutes late, not the Quebec Express. The telegraph operators identified the two trains by numbers – 30 and 34 respectively. Browley had simply typed a zero instead of a four, and that slip sent 26 souls to their deaths in the worst train wreck in New Hampshire history.

Sources:

Annual report of the Railroad Commissioners of the State of New Hampshire

Canaan Reporter, La Presse and other newspapers

Images: Postcards made of the worst train wreck in New Hampshire history.

This story updated in 2022.