Benjamin Edes instigated and paid for the Boston Tea Party – and, to his death, guarded the secret list of all who participated.

Edes along with John Gill published the Boston Gazette and Country Journal, a leading voice for American independence. The Royal Lt. Gov. Andrew Oliver called it ‘that infamous paper.’

“The temper of the people may be surely learned’ from it,” Oliver said.

Benjamin Edes‘ son Peter was convinced his father would have been hanged or sent to England to be tried if he had fallen into British hands. Peter himself served 3-1/2 months in prison for cheering the patriot side during the Battle of Bunker Hill.

“If my father had been like some other men, he might have been worth thousands on thousands of dollars; but he preferred the liberties of his country to all,“ wrote Peter Edes.

Benjamin Edes

Benjamin Edes was born Oct. 14, 1732 in Charlestown, Mass., one of seven children of Peter Edes and Esther Hall. He married Martha Starr sometime around 1754. The next year he and Gill took over the Boston Gazette.

Edes helped form the Sons of Liberty and, through the Gazette, agitated against the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts and the tea tax. The newspaper broke news about tax disputes, the Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party, and it also served as a mouthpiece for Samuel Adams.

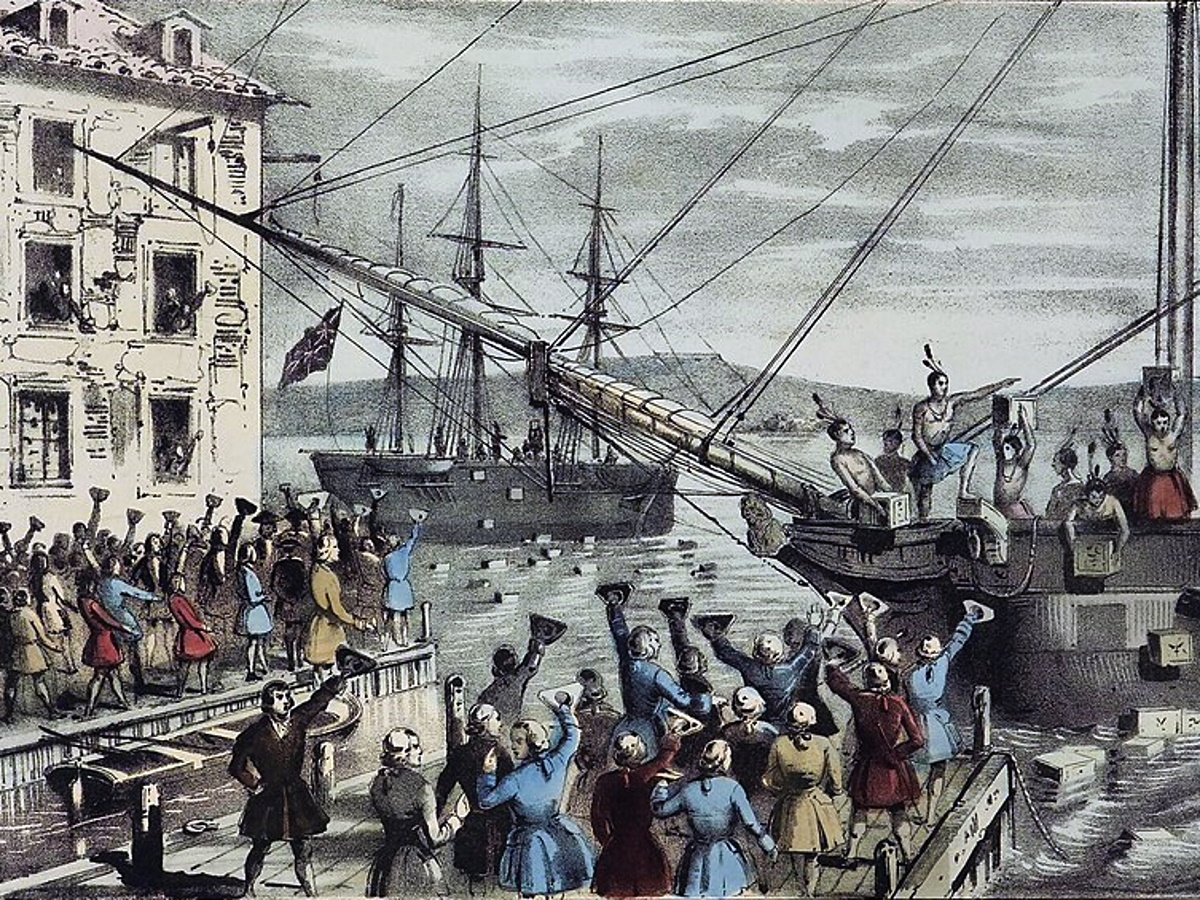

On Dec. 16, 1773, Benjamin Edes hosted a group of men in his parlor before they set out for the Dartmouth, the Eleanor and the Beaver.

His son Peter, who would turn 17 the next day, saw some of what happened. In a letter to his own grandson in 1836, Peter Edes recounted what he remembered of that event.

“I knew but little about it, as I was not admitted into their presence, for fear, I suppose, of their being known,” he wrote.

But he knew more than most.

He remembered that a number of gentlemen met in his father’s parlor in the afternoon before they destroyed the tea. Peter’s job was to make punch for them in another room. He filled the bowl several times.

(The punch bowl now belongs to the Massachusetts Historical Society.)

Eyewitness Account

The men stayed in the house until dark, he supposed to disguise themselves as Native Americans. When the sun set, they left the house and went to the wharves where the vessels lay.

Once the men left, Peter went into his father’s room. But Benjamin Edes wasn’t there. So Peter decided to walk to the wharves where he saw 2,000 people.

“The Indians worked smartly,” wrote Peter Edes.

“Some were in the hold immediately after the hatches were broken open, fixing the ropes to the tea-chests; others were hauling up the chests; and others stood ready with their hatchets to cut off the bindings of the chest and cast them overboard. I remained on the wharf till I was tired, and fearing some disturbance might occur went home, leaving the Indians working like good industrious fellows.”

Benjamin Edes did not fall into the hands of the British. During the Siege of Boston, Edes escaped arrest by disguising himself as a fisherman. He boarded a fishing boat and landed on one of the islands in Boston Harbor, from which he escaped to the mainland

He moved to Watertown, Mass., where he continued to publish the Gazette until 1798. Benjamin Edes died on Dec. 11, 1803.

How the Names Got Lost

Peter Edes later wrote that it was ‘a little surprising’ that the names of the Tea Party remained secret. [My] “father I believe, was the only person who had a list of them, and he always kept it locked up in his desk while living.

“After his death Benj. Austin (a Boston selectman) called upon my mother, and told her there was in his possession when living some very important papers belonging to the Whig party, which he wished not to be publicly known, and asked her to let him have the keys of the desk to examine it, which she delivered to him; he then examined it, and took out several papers, among which it was supposed he took away the list of the names of the tea-party, and they have not been known since.”

This story was updated in 2022.

18 comments

[…] In the run-up to the American Revolution, colonists often gathered at the Old South Meeting House to protest British rule. At a time when Boston's population was 20,000, overflowing crowds came to hear James Otis, Joseph Warren, John Hancock and Samuel Adams denounce the tea tax, impressment and the Boston Massacre. On Dec. 16, 1773, 4,000 angry colonists showed up at Faneuil Hall to discuss the tea crisis. Faneuil Hall couldn't hold them all, so as many as 6,000 gathered at Old South before adjourning to Griffin’s Wharf for the Boston Tea Party. […]

[…] was an apprentice to his father, Benjamin Edes who, with John Gill, printed the radical newspaper Boston Gazette and instigated the Boston Tea […]

[…] 1769, Sam Adams, James Otis, Paul Revere, John Hancock, Benjamin Edes and 350 Sons of Liberty celebrated the fourth anniversary of resistance to the Stamp Act at the […]

My ancestor

His son Peter Edes home in Bangor, Maine will be open to the public on Sat. DEC. 2ND One of five historic homes to be on the tour. Peter and his daughter is buried at Mt Hope cemetery. The second oldest garden cemetery in the U.S. if you can make the tour that would be wonderful. My name is Kenneth Liberty and the address is 23 Ohio Street Bangor Maine. like tbe cemetery Ede’s house is second oldest home in The city of Bangor. We have a print of Benjamin and picture of tbe punch bowl hanving in the front hall. If you are ever in Bangor please stop in. We would love to meet you and show you the house and Peter’s resting place. phone is 207 945 9736

[…] the complete list of the Americans who undertook the Boston Tea Party has never been assembled, Joseph Dyar long said he was one of them and that his wife was one of the women who made the […]

[…] Inside the house is a tea box, said to be among the batch thrown into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party. […]

[…] Farmington, Conn., heard about the events leading to the American Revolution from the town crier Mr. Bull. Here’s how Ellen Strong Bartlett’s great-grandmother described how they learned about the Boston Tea Party. […]

[…] Benjamin Edes, along with his partner John Gill, didn’t fight in the war, but he was nonetheless a revolutionary hero. Edes, more than any other publisher, stoked public indignation over Parliament’s abuse of the American colonies. […]

[…] with the ultimatum, the colonists conducted their now-famous raid on the ships Dartmouth, Eleanor and Beaver. The whole debacle left Hutchinson’s reputation in tatters. While he retained the loyalty of the […]

Just click on the hyperlinks for sources.

[…] 1768, Revere placed an advertisement in the Boston Gazette offering to replace lost front teeth with artificial ones. Two years later, he ran another ad […]

[…] he sent his first shipment of ice to Martinique amid much derision. "No JOKE," reported the Boston Gazette. "A vessel has cleared at the Custom House for Martinique with a cargo of ice. We hope this will […]

[…] final addendum to the list of 18 patriots condemned to death targeted Benjamin Edes and John Gill, who published the pro-patriot newspaper the Boston Gazette. It also named Isaiah […]

[…] evening, every chest from on board the three vessels was knock'd to pieces and flung over ye sides. They say the actors were Indians from Narragansett. Whether they were or not, to a transient observer they appear'd as such, being […]

[…] 1767 at 40 as a vibrant and attractive woman. She eventually married Moses Gill, son of the printer John Gill who helped instigate the Boston Tea Party. John Adams attended their wedding breakfast in 1773, […]

[…] On Dec. 16, 1773, 4,000 angry colonists showed up at Faneuil Hall to discuss the tea crisis. Faneuil Hall couldn’t hold them all, so as many as 6,000 gathered at Old South. Then they adjourned to Griffin’s Wharf for the Boston Tea Party. […]

[…] first shipment of ice to Martinique amid much derision. “No JOKE,” reported the Boston Gazette. “A vessel has cleared at the Custom House for Martinique with a cargo of ice. We hope this […]

Comments are closed.