Peter Edes spent 107 days in a sweltering hellhole of a prison because the British didn’t like his attitude while he watched the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Also, they didn’t like his dad.

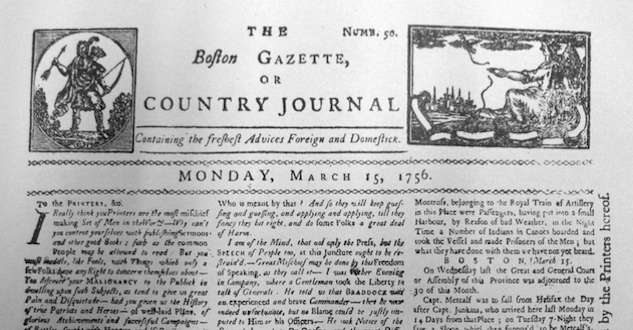

Peter Edes apprenticed to his father, Benjamin Edes who, with John Gill, printed the radical newspaper Boston Gazette. His father managed to escape the Siege of Boston and settle in Watertown, Mass, where he continued to publish the Gazette.

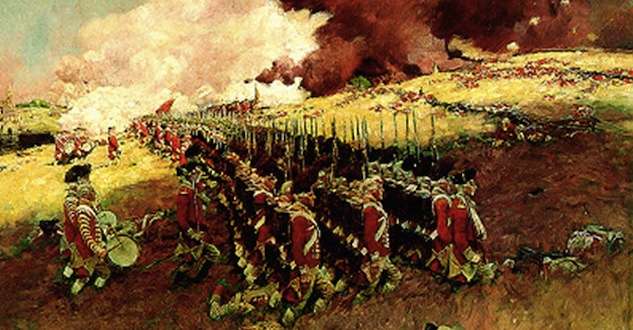

His son didn’t immediately follow him. On April 19, 1775, Peter watched the British retreat from Concord and Lexington, and he failed to hide his joy. That annoyed the regulars. Then on June 17 they didn’t like how he watched the Battle of Bunker Hill with anxious and tearful eyes for the patriots.

Peter Edes

Peter Edes was born Dec. 17, 1756 in Boston and trained from a young age in the patriotism of the American Revolution. John Hancock, John Adams and Joseph Warren congregated in his father’s office. On the day before his 17th birthday, he refilled the china punch bowl several times for them as they dressed as Indians to throw tea into Boston Harbor.

British authorities arrested him two days after the Battle of Bunker Hill, having watched his reaction to the battle from Copps’ Hill. They imprisoned him for keeping a weapon. By the time he was released, only 11 of the 29 prisoners taken at the Battle of Bunker Hill were still alive.

That isn’t surprising, considering more revolutionaries died in British prisons than on the battlefield.

Edes kept a diary in which he recorded the prisoners’ sufferings. They were confined in close, stifling quarters, beaten, insulted and starved. For his first 37 days he was only allowed bread and water. The wounded weren’t given medical care.

Oaths, Curses, Debauchery, Blasphemy

Edes found the soldiers’ language: “a complicated scene of oaths, curses, debauchery and the most horrid blasphemy,” which they kept up night and day because it offended the prisoners.

Edes called it “the suburb of hell.” On August 15, he wrote:

Close confined; the weather very hot. Died, Capt. Walker, a prisoner taken at Bunker’s Hill. Swearing began at 3 this morning, and continued all day. The place seems to be an emblem of hell. At 9 at night, most horrid swearing and blasphemy. The worst Man of War is nothing compared with this diabolical place. They sometimes gave us water in the pail in the morning, and by the heat of the weather and our cell, it grew very warm, and they would not change it, and d—-d us, saying we must have that or none.

Peter continued to work for his father after his release, first as an apprentice and then as a partner. He moved to Newport, R.I., for a while and began to print the Newport Herald on March 1, 1787. He returned to Boston in 1791 and printed books. An especially influential volume was Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Susan B. Anthony donated her copy to the Library of Congress.

Maine

Edes then moved to Maine, where he worked as one of the first publishers and the first printer in Bangor. The printing press he brought to Bangor by ox-cart was donated to the Bangor Historical Society, but was destroyed in a fire.

As an old man, he had suffered financial reverses, and his friends thought to print his prison diary as a way to raise money for him

Peter Edes died March 29, 1840, at the age of 82. According to his obituary, he was the oldest printer in the United States at the time of his death.

“BostonGazette 1756” by Boston Gazette, Justin Winsor. Memorial History of Boston. 1880. (Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library/Rare Books.). Licensed under public domain via Wikimedia Commons. This story was updated in 2024.

2 comments

Peter Edes, my Great grandfather 5 generations back. Amazing

[…] moved to Watertown, Mass., where he continued to publish the Boston Gazette until 1798. The British arrested his 17-year-old son Peter for 3-1/2 months, mostly because they hated his […]

Comments are closed.