In 1652, Massachusetts Puritans decided to bring the English Civil War to North America by taking over Anglican Maine.

The year before, Puritans in England had won the final battle of the English Civil War. They had abolished the bishops, beheaded Charles I, exiled Charles II and put Parliament in control of the government. They also did away with High Anglican practices that smacked of Roman Catholicism.

The Massachusetts Puritans, emboldened by their success in England, sent negotiators to the scattered settlements along Maine’s west coast. One by one, the Maine communities agreed to the Puritan ‘suggestion’ that they join the Bay Colony. The Massachusetts militia may have helped them make up their minds.

The Puritans then gave new names to some of the Anglican Maine communities – names some of the Mainers didn’t like one bit.

East vs. West

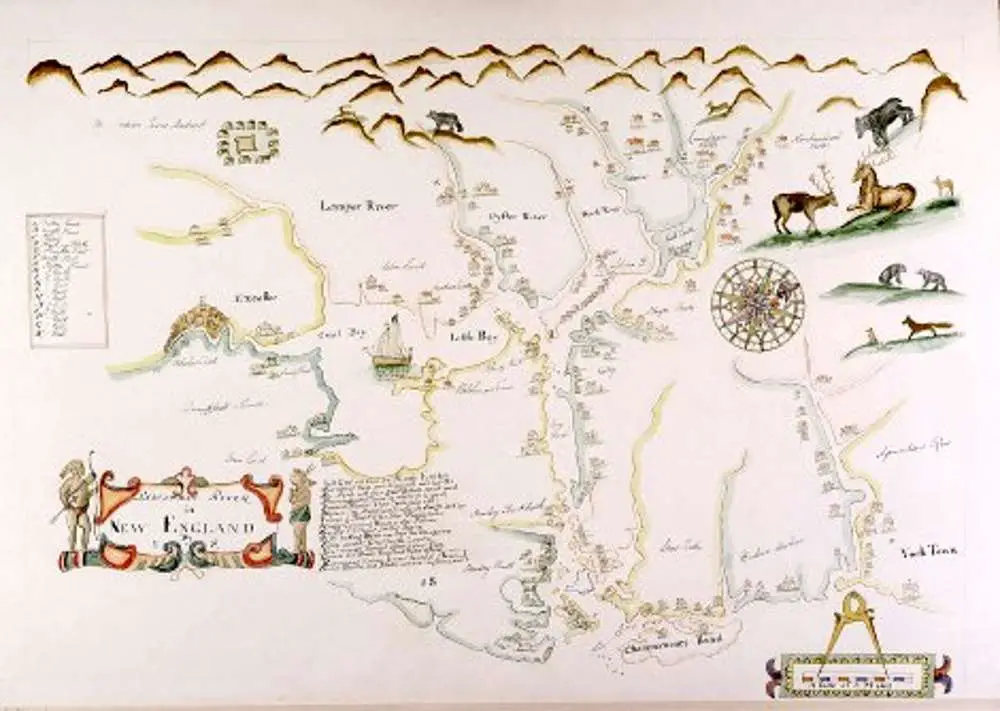

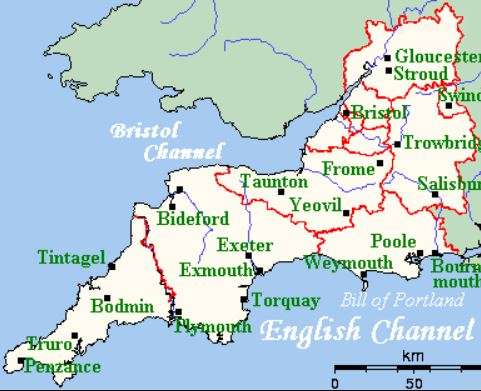

Take a look at the place names along the southern Maine coast: Kittery, Wells, Biddeford, Dartmouth and Falmouth. They mirror place names in Southwest England, known as the West Country.

Historians compare the region to the American South. In the 17th century, it had large plantations and a rural population. Its people were more likely to support the Anglican Church than were the Puritans in eastern England.

Now take a look at Massachusetts place names: Boston, Lynn, Ipswich, Yarmouth, Cambridge, Essex. They come from eastern England, or East Anglia.

East Anglia gave names to 63 percent of Massachusetts towns founded before 1660. Most of those had names from towns within 60 miles of Haverhill in the East Anglian county of Suffolk.

That’s because the Puritan elite of Massachusetts came from East Anglia.

Unlike the West Country, East Anglia in the early 17th century was urban, entrepreneurial and a hotbed of Puritan opposition to the monarchy and its High Anglican practices.

Sir Ferdinando Gorges

Sir Ferdinando Gorges, born around 1565, came from an Anglican family that claimed royal descent. A military man loyal to King James I, for a time he served as governor of Plymouth in the West Country.

Gorges decided to colonize the New World after receiving three captured North American Indians from an English ship captain.

In 1607 Gorges helped finance the failed Popham Colony in present-day Phippsburg, Maine. The Popham settlers brought with them an Anglican priest, Richard Seymour, brother to Henry VIII’s wife Jane Seymour. Richard Seymour conducted the first Anglican service in America.

In 1620, King James I granted Gorges a patent for ‘planting, ruling, ordering and governing’ the territory between Virginia and New France.

Gorges, as head of the Council for New England, gave himself and his partner John Mason a grant for all lands between the Merrimac and Kennebec rivers.

Mason took New Hampshire, and Gorges took the territory north of the Piscataqua River. He called it New Somersetshire after his own home in England.

Anglican Maine

While Gorges was off fighting the French in 1627, the Massachusetts Bay Company got a royal charter for Massachusetts. Gorges thought Massachusetts belonged to him.

To add insult to injury, the Massachusetts Puritans believed in self-rule. Gorges wanted his territory run by Anglican feudal lords and their deputies.

Gorges tried maneuvering in Parliament to get Massachusetts back. His efforts sparked antagonism between the Anglican, Royalist Gorges and the Puritan leaders of Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, a trickle of Anglicans from the West Country came to fish, farm and trade along the southern Maine coast in places they called Black Point, Blue Point, Stratton’s Island, Spurwink and Casco.

Gorges tried to establish another colony between the Saco and Kennebec Rivers, which he called the province of Lygonia after his mother, Cecily Lygon. Another settlement took Gorges’ own name — Gorgeana.

The settlers in Anglican Maine and Lygonia squabbled over who owned what land. Their disunity didn’t help them when the Massachusetts Puritans came calling.

What’s In A Name?

Since the arrival of the Winthrop fleet in 1630, Massachusetts had steadily grown in size and in wealth. With an organized government, its citizens had the rights of trial by jury and the freehold tenure of land. Freemen elected councils to write bylaws and deputies to attend the General Court, observed historian Hannah Farber.

By 1650, Massachusetts’ rapidly growing population reached 14,000. In contrast, only about a thousand English colonists lived in Maine, and most of them barely scratched out a living.

Massachusetts Gov. John Endecott sent commissioners to their eastern neighbor, where they went from town to town. They suggested to the people of Maine and Lygonia they might have more legal rights and more prosperity if they joined Massachusetts Bay. The Puritans also may have mentioned the size of their militia.

Town by town the Maine settlements voted to join Massachusetts. In 1652, Kittery came to Massachusetts, and the next year Wells, Cape Porpoise and Saco followed. Lygonia caved in 1658 and the Puritans changed its name to Maine.

Names carried great importance to the early New England Puritans. And so when Gorgeana agreed to join Massachusetts, the Puritans renamed it York. Gorges had died by then, but the Puritans undoubtedly didn’t want to honor the Royalist who tried to take away their charter. The name York carried a special sting as it was shared by the Royalist city that fell to Parliament during the just-ended English Civil War.

New Overlords in Anglican Maine

The Massachusetts Puritans also renamed two towns after the last Royalist strongholds to fall to the Puritans in England.

Black Point, Blue Point and Stratton’s Island became Scarborough, which in England had surrendered only a month before the execution of Charles I.

Spurwink and the Casco Bay settlements would be called Falmouth, later renamed Portland. Queen Henrietta and the Prince of Wales (the future Charles II) found safety in Pendennis Castle in Falmouth for five months before it surrendered to the Puritans.

“The Puritans of Massachusetts imposed the names Falmouth and Scarborough in conquest, a reminder to the population of their fate and of their new overlords,” wrote historian Emerson W. Baker in an essay, Formerly Machegonne, Dartmouth, York, Stogummor, Casco and Falmouth: Portland as a Contested Frontier in the Seventeenth Century.

After the monarchy was restored in England, a royal commission came to Maine in 1665 and put the province under royal authority. But it took only three years for the Massachusetts Puritans to retake control of Anglican Maine.

Not until March 15, 1820 would Maine separate from Massachusetts as a result of the Missouri Compromise.

This story was updated in 2023.

Images: West Country England, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2530598.

5 comments

[…] English colonists had settled Maine under a charter granted to Fernando Gorges. York was successively known as Bristol, Agamenticus and, in 1642, as Gorgeana. Gorges died 10 years later. Massachusetts Bay Colony then absorbed Maine and renamed the settlement York. […]

[…] Massachusetts had taken over Maine in the 1650s, and by 1731 royal Gov. Jonathan Belcher cast a greedy eye on New Hampshire as well. […]

[…] Quakers and the Puritans both criticized the Church of England, but the similarities ended there. The Puritans practiced rites of baptism and communion and […]

[…] his disapproval with how the Massachusetts Puritans took over Maine towns, originally settled by Anglicans like himself. And he makes clear his disdain for the poor, weak […]

[…] to the early New England Puritans. And so when Gorgeana agreed to join Massachusetts, the Puritans decided to rename it York. The name York carried a special sting because it was the name of a Royalist city in England that […]

Comments are closed.