On Sept. 7, 1881, Boston’s temperature hit 102 degrees, but New Englanders breathed a sigh of relief because the latest yellow day had cleared.

On a yellow day, as the name suggested, everything seemed to turn yellow.

On September 6, a heavy, burnt yellow mist had covered New England and beyond, from Millinocket, Maine, south to Virginia and west to Chicago. It made blue flowers look bronze, silenced street vendors, forced farmers to stop work and made Second Adventists don their ascension robes for their trip to heaven.

It was twilight at noon – just like the Dark Day a century ago.

Dark Days

Yellow days, also known as dark days, seemed to happen more frequently in New England than any place else in the world.

Fred Gordon Plummer reached that conclusion in Forest fires: their causes, extent, and effects, with a summary of recorded destruction and loss, a U. S. Forest Service book published in 1915. He reasoned that storm centers and air currents converge over the region. When the great forest fires broke out in the northern United States, winds carried the smoke to New England.

Usually they begin with a gradually increasing gloom until artificial light is necessary. They may last from a half hour to several days.

Most dark days should more properly be called ‘yellow days,’ wrote Plummer, and even the Dark Day of 1780 was preceded by a gradually increasing yellowness and an odor.

The region’s first recorded yellow day occurred on May 12, 1706. Then followed:

- Oct. 21, 1716 (11 am-11:30 am)

- Aug. 9 1732

- May 19, 1780

- July 3, 1814

- Nov. 6-10, 1819

- July 8, 1836

- Sept. 2, 1894

- Sept 24-30, 1950.

Dark Day of 1780

The Dark Day of 1780 was the most famous of the yellow days. The skies darkened shortly after dawn, inspiring terror, panic and puzzlement. George Washington, fighting the American Revolution, noted in his diary, ‘Heavy & uncommon kind of Clouds–dark & at the same time a bright and reddish kind of light intermixed with them.’

The Dark Day of 1780, detail from mural painted by Works Progress Administration artist Delos Palmer in Stamford, Conn., Old Town Hall.

They have other names: dry fogs, Indian summers and colored rains.

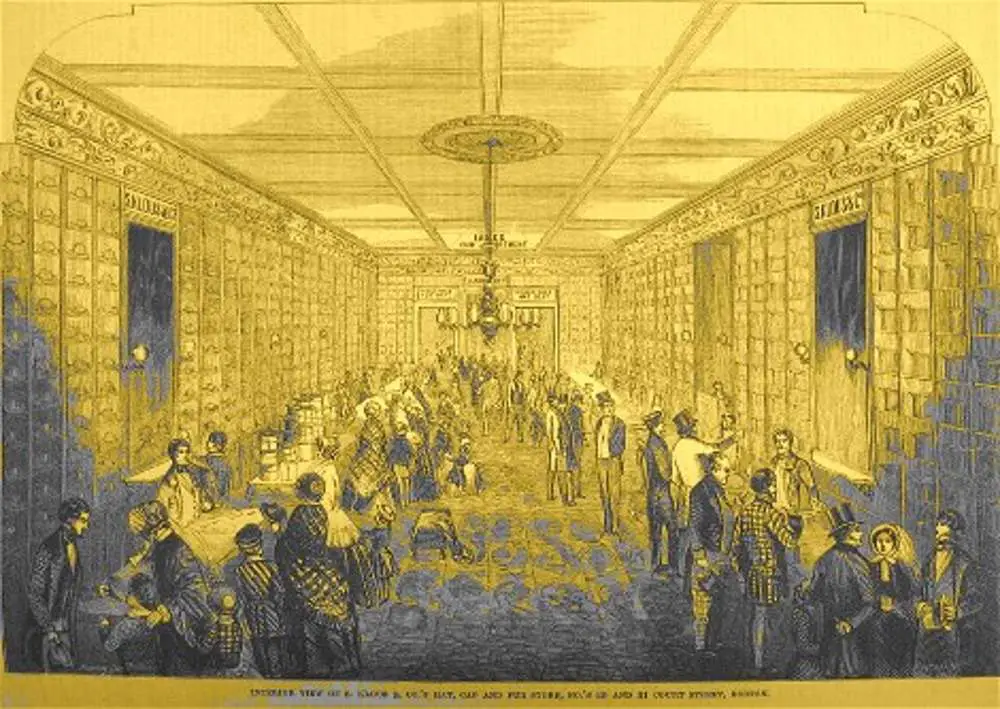

The Yellow Day

A tremendous forest fire in Michigan’s thumb-shaped peninsula caused the Yellow Day of 1881. It burned about a million acres, killed 282 people and destroyed 20 villages. It sent smoke, soot and ash eastward high into the air.

An hour after dawn on the Yellow Day in 1881, “the moist air, saturated with smoke and perfectly still, seemed to thicken into a heavy screen of mist, that hung low and was of a strange yellow hue,” according to Harper’s Magazine.

The Yellow Day created strange, even lurid, atmospheric effects. Lights flashed and gleamed with dazzling brightness and distinctive whiteness, reported the Boston Globe.

In the Public Garden, “Flowers of pink turned pure white, and the scene blue of the lobelia became a deep bronze, while flowers of yellow became pearly in their whiteness.”

Quiet descended on city streets: The girls who sold peanuts stopped selling their wares, the fruit vendors stood stock still next to heaps of peaches and newsboys subdued their shouts.

Out in the country, farm work stopped, hens went to roost and the cattle stopped feeding. Factories closed for the day and teachers in Fall River and Lowell sent children home from school because it was so hard to read and write.

The Yellow Day kept all spectators away from a baseball game between the Bostons and the Worcesters. Instead, throngs of Bostonians rushed to the high roof of the Equitable Building to observe the Yellow Day.

In mid-afternoon, railroad men left depots carrying lanterns, and early afternoon trains lit their lamps. “Nine persons out of ten would have declared that it was evening when it was but 2 O’Clock,” reported the Globe.

End of the World?

A 16th-century English soothsayer named Mother Shipton stoked fears that the Yellow Day meant the end of the world. She had supposedly made prophesies that first appeared in a book in 1641, 80 years after she died. A later edition contained the famous prediction,

The world to an end shall come

In eighteen hundred and eighty one.

Groups of Second Adventists believed the end was coming on the Yellow Day. They wore their ascension robes to local schoolhouses in Worcester, Woonsocket and Hartford to await the world’s end.

A rural deacon believed the end of the world was near, according to Harpers.

His neighbor said, “You allus said you wanted to be in heaven, and I guess you’ll be there before dinner. You ought to be happy, anyway.”

The deacon had no such luck. The air began to clear by 5 pm, and stars twinkled in the sky three house later.

This story about the Yellow Day of 1881 was updated in 2023.

3 comments

Did these days of darkness coincide with eclispes?

Yes, If you sign up as a member (just send us your email address and create a password) you will receive our weekly newsletter. Thanks for your interest!

No Carole, they did not coincide with eclipses. A great place to read about these phenomena and their likely causes is JSTOR.ORG…a free site that publishes original works chronicling events. Here is the link to the 05/19/1780 event. Most likely these phenomena are the results of wildfires or volcanic activity.

An Account of a Very Uncommon Darkness in the States of New-England, May 19, 1780

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25053760?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Comments are closed.