The beautiful Ethel Reed blazed like a meteor across Boston’s artistic firmament in the 1890s, but after a broken engagement she all but disappeared.

She was one of the first, if not the first, woman to gain prominence as a graphic designer, and she did it by her 18th birthday. At 22, she moved to Europe. By 24, she disappeared from the historical record.

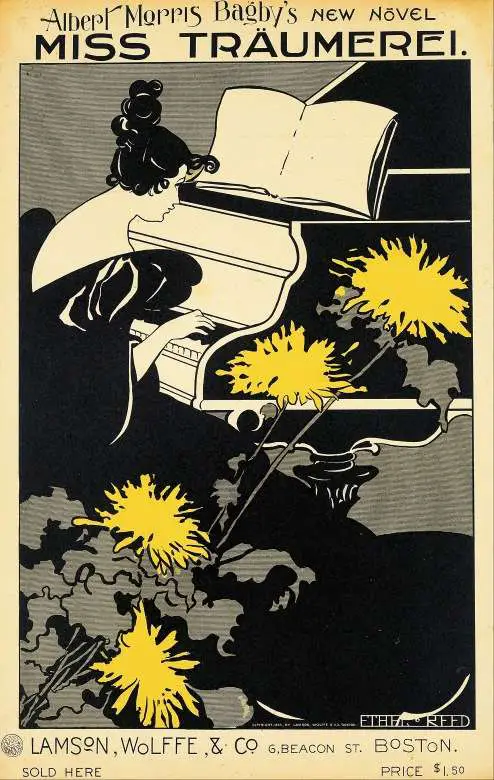

One critic noted Ethel Reed’s work included tangled forms that seem full of secret and illicit meanings. What lurks in those trees, for example?

Ethel Reed

Ethel Reed was born March 13, 1874 in Newburyport, Mass., the daughter of Irish immigrants Edward Eugene Reed and Mary Elizabeth Mahoney. Her father died when she was young, his obituary described him as a “well-known and popular photographer.”

In 1890, mother and daughter moved to Boston, a good choice for aspiring illustrators. The city then was a publishing powerhouse, and the books and newspapers it produced needed decoration.

Ethel studied briefly at the Cowles Art School and apprenticed as a painter of miniatures. She mostly taught herself, however, and didn’t seem to have a plan. Perhaps her addiction to opium, dating from her teens, explains why.

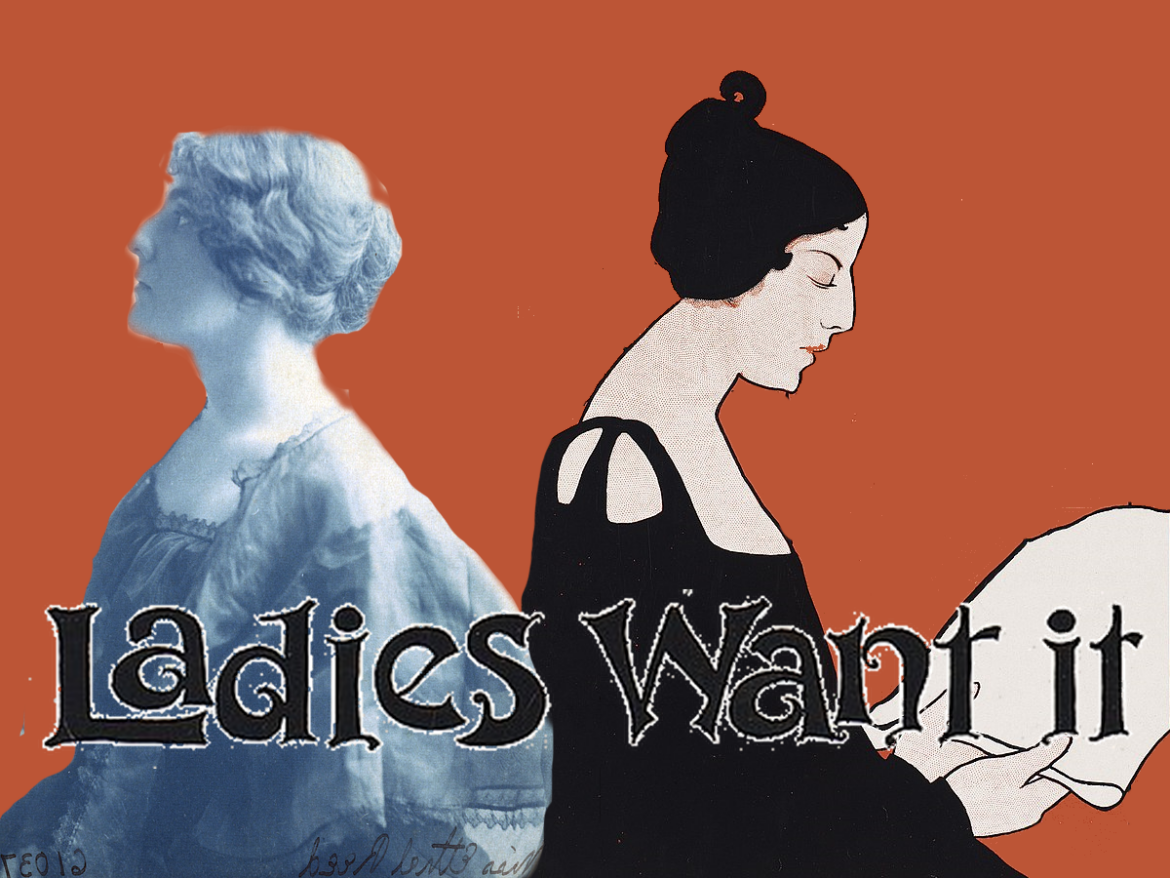

One day a friend saw her doodling and suggested she submit a design to the Sunday Herald, a special edition of the Boston Herald for a women audience. She did, and rocketed to fame.

Her 1895 design, like much of her work, seems whimsical at first glance but then suggests a darker, more provocative theme.

That first illustration for the Sunday Herald includes a demure woman with a swanlike neck — and poppies, which produced the drug Reed used. It also had the caption, “Ladies Want It.” Coming from a sexually active woman, that could mean something other than a newspaper.

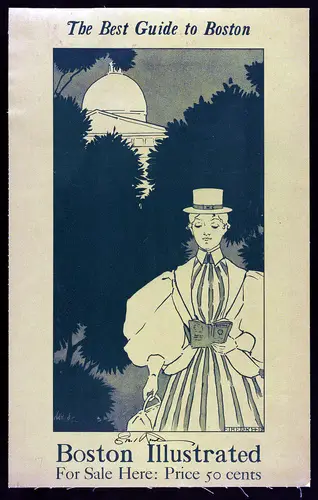

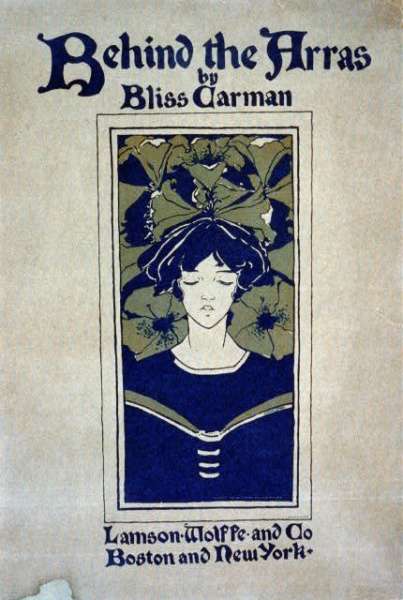

During the 1890s Americans had a mania for posters. Ethel Reed satisfied that appetite, and then some.

In a two-year burst of creativity she gained international fame for her posters, as well as for her illustrations and endpapers.

Gossip columnists found her fascinating, and she emerged as a media celebrity, something she encouraged. She became the most famous woman artist in America.

No Man in Her Room

But she downplayed her sexual adventures. “If anyone caught her with evidence of a man having been in her room, like a top hat on the bed, she would claim that they were artistic props: ‘Obviously, there was no man in my room’,” Angelina Lippert told ARTNews. Lippert organized a show of Reed’s work at Poster House in New York in 2022.

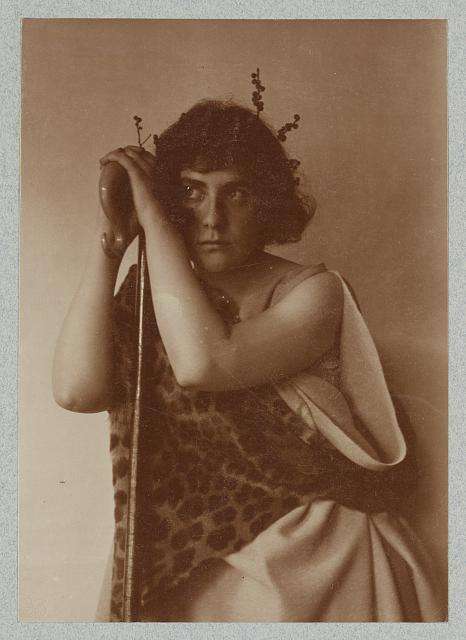

Ethel Reed fell in with a crowd of Boston Bohemians that included Ralph Adams Cram, Bertram Goodhue and Fred Holland Day. Day was one of the first to view photography as an art, and he took an arty shot of Ethel Reed as ‘Chloe with leopard skin, berry branches in hair, and shepherd’s crook.’

She posed for Frances Benjamin Johnston, the first woman photojournalist. Johnston took glamorous shots of Reed in a black dress, which Reed handed out to newspapers.

Love Affairs

Philip Leslie Hale was another Boston Bohemian artist, but a Brahmin as well. Hale was the son of Edward Everett Hale, the brother of Ellen Day Hale, a relative of Nathan Hale and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Phillip Leslie Hale, self-portrait

He and Ethel Reed fell in love and got engaged to be married. His family disapproved, and broke them up. They had planned to honeymoon in Paris. When the engagement fell through, she and her mother sailed for Europe.

In England, she finished up a few commissions for the avant-garde British publication The Yellow Book, co-edited by Aubrey Beardsley, until about 1898. But with few friends and fewer connections in Europe, she couldn’t find work. A former lover offered to help. She replied, “I owe no man anything—neither fidelity nor explanations,” she wrote to him. “I am my own property.”

Then she disappeared. Little was known about her until William Peterson researched her for his book, The Beautiful Poster Lady: A Life of Ethel Reed, published in 2013. He learned she took a series of lovers and bore two children fathered by two of them. Then she married an English army officer named Arthur Warwick. The marriage fell apart quickly. They separated during their honeymoon. In her last years she lived in poverty, addicted to drugs and alcohol. She died in 1912. Her death certificate listed her cause of death as misadventure

Her work has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, the Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

This story about Ethel Reed was updated in 2023.

Images: “Ladies want it” By Ethel Reed, b. 1874 – [1], CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84737084. Best Guide to Boston Reed, Ethel, Artist. The best guide to Boston. Boston illustrated for sale here: price 50 cents / Ethel Reed. , None. [Place not identified: publisher not identified, between 1898 and 1900] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645310/. Ethel Reed by Frances Benjamin Johnston Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. Miss Ethel Reed. , None. [Between 1890 and 1910] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014645308/.

4 comments

[…] to poor children. He belonged to a/the circle of Boston Bohemians that included Ralph Adams Cram, Ethel Reed and Louise Imogen […]

[…] https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/ethel-reed-the-beautiful-poster-lady-who-disappeared/ […]

[…] you like this story about Audrey Munson, you may also enjoy this story about Ethel Reed (here), the beautiful poster model who disappeared. This story was updated in […]

[…] https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/ethel-reed-the-beautiful-poster-lady-who-disappeared/ […]

Comments are closed.