On Sept 28, 1859, James Worster led 50 angry farmers, mill operators, loggers and laborers in a vain effort to destroy a 250-foot dam that controlled the outflow of Lake Winnipesaukee. The dam regulated how much water flowed into the Merrimack River and powered the cotton cards, the spinning frames and the power looms of the enormous textile mills in Lowell and Lawrence, Mass. It was just one battle in the Winnipesaukee water war that had gone on for years.

People would call the attack on the dam and the fight that broke out afterward the Lake Village Riot. Lake Village now exists as Lakeport, a neighborhood of Laconia, N.H. In 1858, it belonged to neighboring Gilford. A growing commercial hub, it had shops, a foundry, a machine shop and mills powered by the water that flowed from Lake Winnipesaukee to Opechee Bay.

That dam and the powerful out-of-staters behind it had damaged the farms and businesses of the Lakes Region. Fed up with the out-of-state corporations, the New Hampshire men then vented their anger with axes and iron rods.

The Lake Company

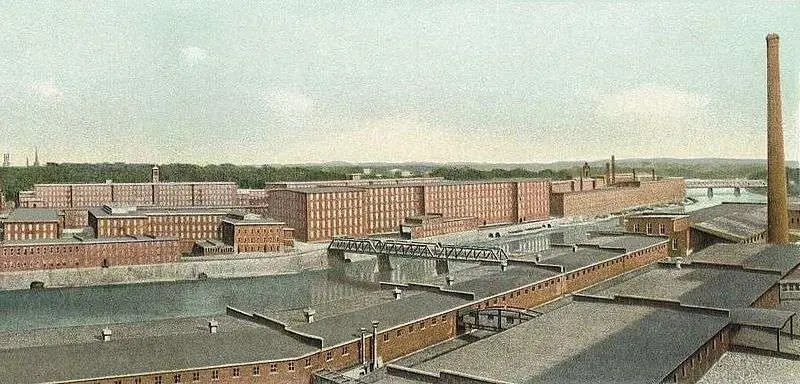

The would-be dam destroyers faced a formidable opponent: a hydraulic empire known as the Lake Company, owned by powerful Massachusetts manufacturers. Their giant mills needed hydraulic power to operate their machinery. The mill owners, known as the Boston Associates, had already reshaped the Merrimack Valley with dams and canals. By 1850 they controlled 45 miles of the Merrimack River and produced more waterpower than in all of France.

Amoskeag millyard, 1911

Still they needed more. And so they set up the deceptively named Winnipissiogee Lake Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company of New Hampshire, also known as the Lake Company.

The Lake Company had little intention of manufacturing anything in New Hampshire’s Lakes Region. But it did intend to seize control of the Merrimack River’s headwaters. Between 1845 and 1856, the Lake Company stealthily took control of 103 square miles of New Hampshire waters, including Winnipesaukee, Squam, Winnisquam and Newfound lakes.

The company fortified dams and deepened channels. By 1859, the mill owners had a system for raising the level of the lakes during the winter and spring. Then during the summer they opened the floodgates to send waterpower to Massachusetts when rivers historically ran low.

Inequality

The citizens of New Hampshire soon figured out what was going on, and they didn’t like it one little bit. Raising the lake levels flooded farmers’ fields. Lowering the lake levels impeded navigation for shippers and ferryboat owners. It also prevented loggers from sending timber downstream. And it deprived local mills of enough waterpower to run their machinery.

Something else fueled the anger of the farmers, millers, loggers and shippers of New Hampshire’s Lakes Region. They grew frustrated with the industrialization along the Merrimack and its impact on New Hampshire’s way of life and its businesses. As New Hampshire’s waters drained away to Massachusetts, they carried away the wealth of the farmers and small business owners to the pocketbooks of powerful industrialists.

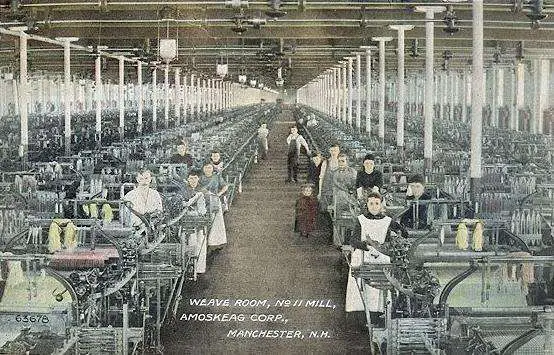

The big Lakes Region towns – Meredith, Gilford, Laconia – were gradually shifting from agriculture to manufacturing. It was an economic rearrangement that didn’t reward participants equally. Farms were not only declining, but becoming less profitable. Mill workers barely earned enough to survive. And inequality was on the rise.

Weaving room of an Amoskeag mill.

The Winnipesaukee Water War Begins

Into the breach stepped James Worster, a 50-something farmer and former blacksmith. Worster wasn’t the only New Hampshire citizen angered by the Lake Company’s economic wrongdoing. Others had tried to wreck dams. Others had asked the Legislature to intervene. And others had sued the company.

But none was as fanatical as James Worster. A Lake County agent said “he ought to be in jail or in an insane asylum.” A New Hampshire judge described him as “so much a man of one idea, that it is of no use to talk with him.”

For years that one idea was to loosen the Massachusetts mill owners’ iron grip on New Hampshire’s lake waters. Worster would, in the end, pay a steep price for his quixotic quest – and for failing to recognize that times were changing.

Up until the mid-19th century, New Hampshire law permitted landowners to destroy a dam upstream if it damaged their property. Worster tried to destroy three of the dams owned by Massachusetts men (and came to grief) between 1847 and 1859. His obsession with the Lake Company would land him in jail.

For years he bounced around New Hampshire, from the Seacoast to Concord to the Lakes Region. With each move, he bought or rented farmland downstream from dams owned by out-of-state mill owners. Whether he deliberately obtained property likely to be flooded is an open question.

James Worster

In 1847, Worster first tried to fight the Great Falls Manufacturing Co., Massachusetts owners of five cotton mills in New Hampshire. Worster leased farmland in Dover, which flooded when a dam held back the Salmon Falls River. He partially destroyed the dam by tearing off an abutment and cutting down its planking. He then threatened to destroy the whole thing. The company went to court and got an injunction against his further damaging the dam.

Salmon Falls River

Two years later, Worster’s daughter Adeline took on the Lake Company. She co-owned land with him in Tuftonboro on the northeast shore of Lake Winnipesaukee. She sued the company, claiming the Lake Company’s dam at Lake Village flooded their property, causing damage. The court dismissed the case in 1852.

While Adeline Worster’s case languished in the courts, her father got hold of more properties. All of them were flooded seasonally by the Lake Company’s machinations – meadowland in Sanbornton, a farm in Gilford along Paugus Bay, and a share of Rattlesnake Island in Lake Winnipesaukee. In 1853, after the court threw out his daughter’s case against the company, Worster threatened to break down the Lake Village dam.

[optinrev-inline-optin1]

A Bloodied Nose

By then, the Lake Company’s people in New Hampshire were keeping a close eye on Worster. The company’s agent, James Bell, obtained from the New Hampshire Superior Court an injunction preventing Worster from interfering with Lake Company property. It couldn’t have hurt that his brother, Justice, Samuel Bell, sat on the court.

Worster then moved to Concord and obtained farmland bordering the Merrimack River in Hooksett. The property lay upstream from another dam that powered the giant Amoskeag textile mills in Manchester. Again it was a dam owned by Massachusetts men. And again it flooded.

The Merrimack River in flood, Manchester, N.H.

At 6:30 a.m. on March 7, 1859, Worster and another man showed up on the Amoskeag Company’s dam. A watchman ordered them to leave. They refused. A fight broke out and the watchman knocked down Worster, then in his 50s, three times and bloodied his nose.

That year the Legislature considered a bill to prevent landowners from destroying dams. It moved through committee until Worster and others appeared at the Statehouse and made an enormous fuss. The bill died.

Four months after his attack on the Amoskeag dam, Worster prepared to launch another. The Amoskeag Company’s agent caught wind of his plans and notified the sheriff. In July, Worster showed up with six men, and they started to rip the flashboards off the dam. The sheriff and his deputies then arrived and arrested Worster.

Worster was not only charged with conspiracy, but pressured financially by the Amoskeag Company. An agent bought an unpaid note in Worster’s name and got a lien put on the Hooksett property for nonpayment.

A Losing Battle for the Lake

By the fall of 1859, feelings were running so high against the Lake Village dam that the Lake Company took extra security precautions. The company’s office was practically on top of the dam, and an engineer was told to find “two or three men that would be sure and reliable in case of trouble.”

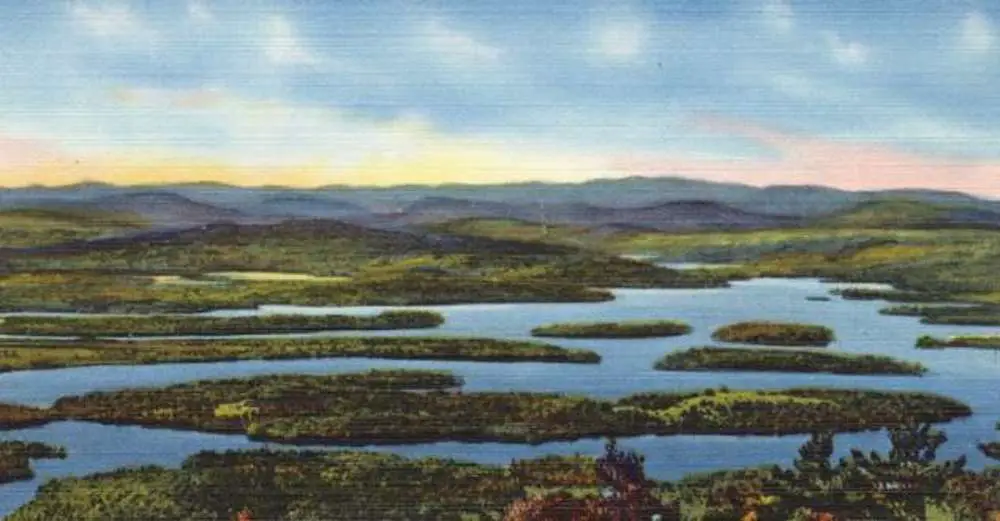

Lake Winnisquam

In August, Worster complained to the Lake Company that the dam had overflowed his properties along Lakes Winnisquam and Winnipesaukee. At that point he was on trial for trying to destroy the Amoskeag dam, and he was still enjoined from damaging the Lake Company’s dam in Lake Village.

That didn’t stop him.

Dam Trouble

The riot itself was preceded by a skirmish on the morning of Sept. 28, 1859. A few determined men showed up at the Lake Village dam. They intended to remove planking, which would allow the lake water to drain off their properties. They believed they were acting within the law.

When the men showed up, the sheriff arrived and sent them away. Undeterred, they came back in the afternoon and began removing the planking. The Lake Company’s agent, Josiah French, and his assistant tried to stop them. In the course of the struggle, French’s assistant struck one of the men on the hand with an iron bar. Some of them tried to push French off the dam.

The dam attackers left again, only to return around nightfall with a larger crowd. Worster arrived with the 50 men wielding axes and iron bars. They came from as far away as Concord. And they brought with them a law enforcement officer who arrested French and his assistant for assault and battery.

When the officer took the Lake Village agents away, he left the field clear for a serious assault on the dam. Fifty angry men with axes and iron bars bashed away at the hated structure. They did some damage, but may not have realized how hard it would be to destroy a tight, seven-year-old, 250-foot stone dam.

Perhaps they could have demolished the dam, but, according to the Winnipesaukee Gazette, “the big boys” of the village came to rough them up. The big boys were probably reimbursed by the Lake Company for their efforts. “The crowd was summarily dispersed, without much regard to ceremony – some of whom were not handled very lightly,” reported the Gazette.

Prison

A raft of litigation followed the melee. Seven of the rioters were charged with attempting to kill Josiah French by pushing him off the dam. The trial ended in a hung jury.

Squam Lake, another front in the Winnipesaukee water war

French was then sued for assault because he’d clubbed a rioter’s hand with an iron bar. A jury acquitted him.

Worster was charged with contempt for rioting after he’d been enjoined against interfering with the Lake Company’s property. The litigation dragged on for several years, during which Forster lost his temper and attacked the Lake Company’s lawyer.

Finally, he was convicted and sentenced to three months in prison and a $500 fine. Worster then gave the Lake Company no more trouble.

The Lake Company also succeeded in convincing the court to issue an injunction against eight of the rioters similar to the one that landed Worster in jail.

End of the Winnipesaukee Water War

The courtroom victories arising from the Lake Village Riot enabled the Lake Company to consolidate its control over New Hampshire’s water. For the next few decades, the Lake Village monopoly remained intact.

Eventually, the mills replaced hydropower with steam. The Lake Village’s control of the lakes would only be loosened by the decline of New England’s textile industry, which began to move south in the 1920s. By the 1930s, the New Hampshire state government would take control of the Lakes Region water flow.

Today, the state of New Hampshire’s Dam Bureau runs the Lake Village dam. And the dam operator still works out of the Lake Company’s old offices.

We are indebted to Nature Incorporated: Industrialization and the Waters of New England, by Theodore Steinberg for this story. This post about the Winnipesaukee water war was updated in 2024

11 comments

[…] Winnipesaukee Water Wars and the 1859 Fight for NH Property Rights […]

[…] Winnipesaukee Water Wars and the 1859 Fight for NH Property Rights […]

[…] Winnipesaukee Water Wars and the 1859 Fight for NH Property Rights […]

[…] Winnipesaukee Water Wars and the 1859 Fight for NH Property Rights […]

[…] Winnipesaukee Water Wars and the 1859 Fight for NH Property Rights […]

[…] International Paper Company's mill at Bellows Falls in Vermont. The logic was this: the mill was powered by water in the river and, to get access to that water, it had to extend part of its plant beyond the low-water mark and into […]

[…] They are buried in Red Hill Cemetery in Moultonborough, a small town on the north shore of Lake Winnipesaukee. […]

[…] Manchester, the factories were powered through an arrangement whereby water from the Merrimack River could be diverted to turn the shafts that drove the equipment. The river worked in conjunction with the Corliss […]

[…] The Winnipesaukee Scenic Railroad offers a one- and a two-hour historic train ride in restored coaches along the western shore of New Hampshire’s biggest lake. Passengers can board at the station in Meredith, or at the Weirs Beach Station on the historic boardwalk. During the historic train ride they never lose sight of Lake Winnipesaukee. […]

[…] off and private). But it still exists, taking up 20,000-plus acres – roughly half the size of Lake Winnipesaukee. You'll find it in Sullivan County near Claremont on the borders of Grantham, Croydon, Cornish and […]

[…] Weirs” on New Hampshire’s Lake Winnipesaukee, has been a popular summer resort since shortly after the last Ice Age, when the continental ice […]

Comments are closed.