Just how rowdy was a New England colonial Christmas? It depended on who was celebrating. But it bore little resemblance to Christmas today, and New Englanders found it a touchy subject from the start.

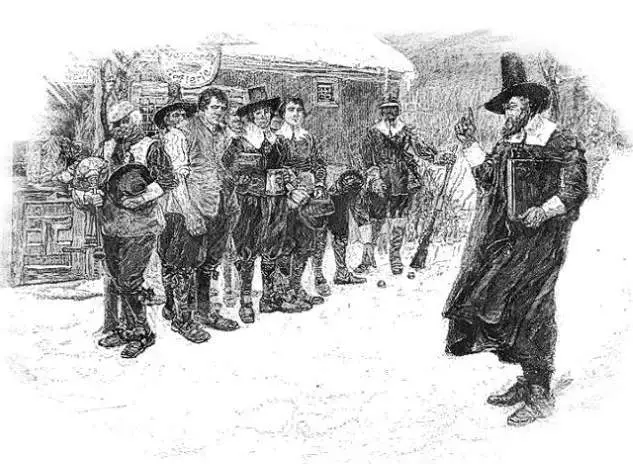

Illustration of an early New England colonial Christmas tradition: Plymouth Gov. William Bradford putting down the Christmas revels. (Howard Pyle)

The Pilgrims who arrived in Plymouth were a mix of people. They were led by separatists who despised the Christmas traditions of the Anglican Church as well as the Roman Catholic Church. They wanted to establish their own protestant churches, free of Christmas.

But many of the Pilgrims did not come to America for religious reasons at all. They were craftsmen or farmers recruited to ensure the colony would survive, and they simply wanted to make a better life in America.

New England Colonial Christmas

On their first Christmas at Plymouth, the Pilgrims celebrated the best way they knew how: They worked right through it. By the next year, Christmas traditions began infiltrating the group, and Gov. William Bradford had to put down the celebrations. He went so far as to call the Christmas treat mincemeat pie ‘idolatrie in a crust.’

As the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony gained ascendance, they had plenty of disagreements with the Pilgrims in Plymouth. But they largely agreed in their dislike of Christmas.

There remained in their midst, however, people who did celebrate Christmas with gusto. The fishing communities especially embraced the New England colonial Christmas, with their less-literate members mostly celebrating the holiday. Much of what actually happened was never recorded. What was recorded was seen through the eyes of the Puritan theocracy, and they painted an ugly picture of Christmas indeed.

Paganism

The Puritans complained that Christmas arose from an unnatural ideological marriage between the Roman Catholic Church and the pagans. They thought it originated in the Roman festival Saturnalia.

Just how pagan is Christmas? We won’t try to settle that debate. But the New England colonial Christmas increasingly irritated the Puritans, and they decided to stomp it out.

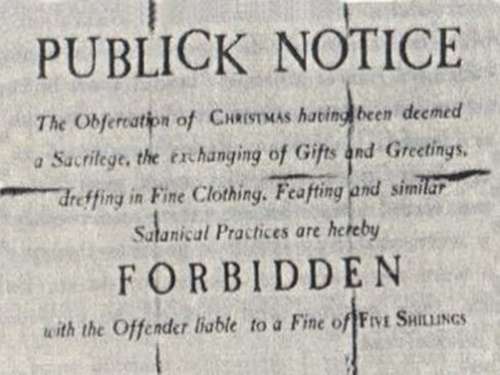

In 1647, the reformers in England outlawed Christmas. And the Puritans in Massachusetts and Connecticut soon followed suit. People who celebrated Christmas would be subject to a fine of five shillings.

In 1662, a Beverly, Mass., man found himself in court for hosting a drunken gathering on Christmas Day. He was a troublemaker whose family frequently tangled with Puritan society. His wife would eventually die on the gallows, but that’s another story.

More Mayhem

A second glimpse of Christmas mayhem occurred on Christmas Day in 1679 in Salem, Mass. Joseph Foster, Benjamin Fuller, Samuel Brayebrooke and Joseph Flint decided they wanted some booze for the holiday. They knew 72-year-old John Rowden had made perry, a liquor made from pears. So they dropped in to pay him an unscheduled visit.

Rowden told them to get out. Fuller refused, saying, “it was Christmas Day at night and they came to be merry and to drink perry, which was not to be had anywhere else but here and perry they would have before they went,” according to court records. The encounter ended in a fight and stolen property.

Twelfth Night (The King Drinks), by David Teniers the Younger (1634-1640), foreshadowing the New England colonial Christmas.

Drinking was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to Christmas debauchery. The New England colonial Christmas included wassailing, mumming, gambling and feasting.

The Puritans constantly struggled to keep Christmas under control. The hoi polloi embraced the New England colonial Christmas as quite a good time.

With the harvest over, the cupboards full and the long winter yet to come, December seemed a perfect month for a ripping good celebration.

Lord of Misrule

In England and elsewhere in the colonies, towns would appoint a “lord of misrule.” This custom borrowed from Saturnalia as well. Generally the towns appointed someone of lower standing to this role to serve as master of ceremonies of the Christmas celebration either up to or including the Twelfth Night festivities.

The reason? During the New England colonial Christmas, people reversed their roles and the poor ruled over the wealthy. In addition to the feasting and drunkenness, the more outgoing celebrants used the holiday as an excuse for wassailing. Wassailing involved barging into the houses of the wealthier citizens, singing a song or two or putting on a short skit, and demanding food, drink and money.

Figgy Pudding

Perhaps you’ve sung the Christmas carol, We Wish You a Merry Christmas, with its chorus of “Oh, bring us a figgy pudding…we won’t go until we get some.” They meant it.

Figgy pudding with flaming brandy

The more obliging citizens would fork over the goods. Others, however, declined — resulting in fights, rock-throwing and hard feelings. Even more abhorrent to the Puritans was the sexual promiscuity that accompanied Christmas. Celebrants cast aside their inhibitions.

One of the more colorful New England colonial Christmas traditions was mumming, in which men dressed like women (and vice versa) or simply disguised themselves in a range of costumes. Mumming could be as innocent as street theater or as bawdy as a loosely disguised roving orgy.

The Puritan objected to the custom because a person disguised could slip into a neighbor’s house for an assignation without raising eyebrows. How commonplace was the debauchery? It’s probably impossible to say, though the good Puritans wanted nothing to do with it.

In 1681, with the Civil War over in England, the crown began pressuring Massachusetts to embrace the Anglican Church and roll back Puritan reforms. The colony complied by repealing the laws against Christmas. But the holiday remained frowned upon.

The Ghost of Christmas Past

Mad Mirth

In 1687 the Puritan minister Increase Mather railed against Christmas. He declared that those who celebrated it “are consumed in compotations, in interludes, in playing at cards, in revellings, in excess of wine, in mad mirth.”

No one really disagreed. It just didn’t bother some people the way it did Mather and the Puritan leadership.

It would take more than 100 years for Christmas to develop the wholesome, twinkly veneer it has today. While the southern colonies and New York, with its Dutch roots, embraced Christmas earlier, New England Protestants would hold out well beyond 1800.

The rest of the nation also felt the influence of the New England colonial Christmas tradition. In 1789, for instance, Congress held a session on Christmas Day. Businesses throughout New England always opened on Christmas. And children attended school on Christmas well into the 1800s.

The New England Colonial Christmas Gets a Facelift

By the early 1800s, however, with Episcopalians and Catholics already celebrating Christmas, the holdout Protestants felt pushed to join in. Most, though, still considered Christmas a pagan holiday that the Catholic Church had co-opted for its own purposes.

The holiday got a facelift with the poem Twas The Night Before Christmas, published in 1822. and Charles Dickens’ classic A Christmas Carol in 1843. The opposition in the church then began to relent.

Marley’s Ghost, from A Christmas Carol. Original illustration by John Leech from the 1843 edition

After the Civil War, the battle ended. New England joined the rest of the country in embracing Christmas. And Christmas, by the way, embraced New England values, at least to some degree. The over-the-top debauchery and drunkenness gave way once and for all to the quieter, conventional celebrations we know today.

* * *

The Christmas holiday actually began in ancient Rome — and so did Italian cookies. The New England Historical Society’s book, Italian Christmas Cookies, tells you how to make those delicious treats. It also bring you the history of the Italian immigrants who brought them to New England. Click here to order your copy today.

This story about New England colonial Christmas traditions was updated in 2024.

Images: Figgy pudding By Ted Kerwin – originally posted to Flickr as Figgy Pudding with Flaming Brandy, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7162734. Twelfth Night by David Teniers By David Teniers the Younger – PradoWeb Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15885934.

45 comments

Love this article.

Very interesting! Love this article & the links to others!

Great article.

When I was young and went caroling we were often given Christmas cookies.

Love facts like this.

Sounds more fun than the way we celebrate now

Woo-hoo! Twelfth Night! My birthday! A happy Pagan, me!

I tried to do caroling last year with osv people, I’m all for raiding houses for cookies at the same time!

When I was young and we went carolling the adults were often given alcoholic beverages!

I desire some Figgy Pudding; and, I want my FIGGY PUDDING now !!!

I recreated this same painting, a few years back! One of my favorites!

Who knew?

[…] close to Christmas to be celebrating Thanksgiving, remember, they wouldn’t have celebrated Christmas, at least in New […]

[…] New England had in the 17th century banned Christmas – a rowdy celebration quite unlike the family holiday we celebrate today. By the Civil War […]

[…] colonial New England, New Year’s Day was not on January 1. Not because the Puritans didn’t want people to have too much fun on New Year’s Eve. It was about England refusing to go along with the rest of Europe in adopting the Gregorian […]

[…] Sunday services would land you in the stocks. Celebrating Christmas would cost you five shillings. The only holidays they celebrated were Election Day; Commencement […]

[…] meaning in New England, where Puritan tradition discouraged celebration of the holiday because they associated it with drunken revelry. Dickens transformed Christmas into a celebration of charity and goodwill with his immensely […]

[…] Puritans, of course, disdained Candlemas Day, which they correctly viewed as a pagan […]

[…] year on Memorial Day, Christmas Day and July 6 the two police officers brought flowers to her grave in Northwood Cemetery in Windsor, […]

[…] Christmas day in 1862 he would record in his journal: "A merry Christmas' say the children, but that is no more […]

[…] Charles Dickens wasn’t impressed with America on his first visit, but he loved Boston enough to return 25 years later with the story that transformed Christmas in New England. […]

[…] New England Christmas started out as an ordinary work day for Puritans who frowned on the papist revelry of their Anglican neighbors. Over the years it […]

[…] cards were popular in England, where Christmas had been celebrated with far more enthusiasm than in Puritanical New England. Sir Henry Cole is credited with inventing the first ever Christmas card in 1843. He was too busy […]

[…] Dictionary of North American Hymnology reports that is far and away the most frequently published Christmas hymn, appearing in 1400 hymnals and you may feel like you’ve heard it that many times already […]

[…] the story, Stanton got around the Puritan hatred of Christmas by inventing ‘Dutch foremothers’ (the Pilgrims were all English) who had a ‘love for festive […]

[…] Christmas festivities in the 17th century. Things got a little wild. Source: https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/wont-go-get-new-england-colonial-christmas-traditions/ […]

[…] England is as unlikely a place as there is to celebrate Christmas firsts. After all, Puritans in Massachusetts and Connecticut officially banned the holiday. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that most New Englanders took the day off, let alone […]

[…] Her uncle, Smith College professor Harry Norman Gardiner, had invited her to stay in his remote cottage on Jupiter Knoll at Christmas Cove. Explorer John Smith had named the inlet after discovering it on Christmas Day. […]

[…] in Boston was Father Rousselet, who had also been suspended from the priesthood in France. During Christmas Eve Mass in 1789, de la Poterie insisted on participating in the service, which sparked fisticuffs among the […]

[…] Olson died on Christmas Eve in 1967, and Christina Olson died a month later. They were buried on their property in their family […]

[…] Election Cake featured in the Puritan celebration of Election Day, one of the important colonial holidays along with Commencement Day and Training Day. (The Puritans had no use for saints days, which they viewed as Papist abominations, and they even banned Christmas.) […]

[…] And, of course, the Puritans didn’t celebrate Christmas. […]

[…] Charles Dickens didn't think much of American slavery on his first visit in 1842. But he loved Boston enough to return after the Civil War with the story that transformed Christmas in New England. […]

[…] England is as unlikely a place as there is to celebrate a Christmas first. After all, Puritans in Massachusetts and Connecticut officially banned the holiday. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that most New Englanders took the day off, let alone […]

[…] early Puritans didn’t like Easter any more than they liked Christmas. They banned Christmas in 1659, fining anyone five shillings for celebrating the holiday. They […]

[…] Holidays used to be local affairs, and they often moved around the calendar. For many years, the entire United States celebrated only two annual holidays: Washington’s Birthday and the Fourth of July. Much of New England, of course, didn’t celebrate Christmas. […]

[…] Christmas*Auld Lang Syne and Teaching ‘Auld Lang Syne’ from Making Moments Matter* We Won’t Go Until We Get Some: Christmas in New England Colonies(Best for older students…This would be a great discussion starter for you high school age […]

[…] George Washington called Boston's annual Pope Night celebration 'ridiculous and childish.' But the working-class celebrants, especially the young men, loved the wild partying in the streets. It was the biggest holiday of the year (after all, the Puritans had banned Christmas). […]

[…] the 18th century, when the household celebrated New Year’s Day as the main holiday when the Puritanical dislike of Christmas still […]

[…] cards were popular in England, where Christmas had been celebrated with far more enthusiasm than in Puritanical New England. Sir Henry Cole is credited with inventing the first ever Christmas card in […]

[…] based on pagan superstitions, which of course is why the Puritans didn't celebrate the holiday. (The Puritans didn't like Christmas, either.) For the early Puritans, celebrating the Lord's Day 52 times a year was quite […]

[…] law, which fell well within the Puritan New England tradition of restricting or outlawing Christmas celebrations, specifically […]

[…] Today’s wandering Christmas carolers carry on that tradition, too, but in a docile way. The Christmas carol, We Wish You a Merry Christmas, has a chorus of “Oh, bring us a figgy pudding…we won’t go until we get some,” alludes to the mummers’ demands. […]

[…] Sunday services would land you in the stocks. Celebrating Christmas would cost you five shillings. The only holidays they celebrated were Election Day; Commencement […]

[…] themselves. They objected to the Church of England’s embrace of Catholic traditions. The Puritans banned Christmas and viewed Easter with the same disdain. They had no use for hot cross buns, ashes on foreheads, […]

Comments are closed.